Confronting citizens: how can we make “citizen participation” meaningful?

Posted:

11 Nov 2020, 11:24 p.m.

Author:

-

Nigel Ball

Former Executive Director, Government Outcomes Lab

Nigel Ball

Former Executive Director, Government Outcomes Lab

Topics:

Citizen engagementTypes:

From the Executive Director“The idea of citizen participation is a little like eating spinach: no one is against it in principle because it is good for you.”

Sherry Arnstein wrote these words over half a century ago in her famous paper, “A Ladder of Citizen Participation”. Attitudes towards leafy vegetables may not have changed much in that time: many of us still fiercely extol the virtues of spinach-eating without perhaps eating quite as much of it as we should. Perhaps attitudes to citizen participation have not changed much either. You are unlikely to catch many leaders in public service and civil society denying the importance of involving citizens and service users in decisions. But there still seems to be a nagging sense we aren’t doing enough of it. Perhaps it feels difficult because it seems to intersect with some of our deeply-held values about how our societies should operate.

Defining participation

In Arnstein’s analysis, citizen participation was about “a redistribution of power that enables the have-not citizens, presently excluded from the political and economic processes, to be deliberately included in the future.” For her, citizen participation went beyond a basic democratic principle that the governed should participate in governing. It was about the flow of power from stronger to weaker groups within society. Given many leaders in public service and civil society belong to, or at least represent, a more powerful group, Arnstein’s definition of citizen participation implies a demand to give up some power.

Power can be uncomfortable territory for social leaders. It feels like the realm of politics. Lots of efforts to improve social outcomes seek to distance themselves from explicit affiliation with particular political creeds (even if they adhere to one implicitly), as it helps maintain broader buy-in. In the political realm, the idea of “power to the people” is traditionally attributed to the radical left, but recently, the rhetoric has been co-opted and exploited by populist politicians - most notoriously by Donald Trump, who began his 2017 inaugural address with the promise that “we are transferring power from Washington, D.C. and giving it back to you, the American People.” But even Margaret Thatcher in the mid 1980s claimed her party was on “a crusade to put power in the hands of ordinary people.”

The use of this sort of language to support such a range of different political movements proves it retains rhetorical power. But can citizen participation mean something administratively, as well as politically?

Understanding participation

One approach to answering this question is to understand participation as the mechanism through which decision makers are held to account. In a paper published last year called “More than Marketised?”, Our Research Director Eleanor Carter synthesises the thinking of a range of scholars to suggest five broad models for this. The first, “procedural” accountability, is associated with a top-down industrial production-line model of service delivery. It gives service users very little power beyond perhaps some legal redress if things go wrong, but provided due process is upheld, there is little space for citizen engagement. The second is a “corporate” model which uses targets and monitoring for accountability. The targets may have political salience (as in the popular 4-hour maximum wait for hospital emergency departments in England) but service users have no great power beyond that. The third is a “market” model concerned with using competition to drive down cost. In theory this gives users lots of power – it characterises them as consumers who can choose where to take their business. In practice, choice is limited if it is there at all, and because competition drives down cost, quality can be poor everywhere. A fourth model, “democratic”, feels much closer to Arnstein’s definition of “citizen participation”: citizens are asked what they want and delivery is targeted at satisfying those wishes. And finally, an emerging “network” approach emphasises trust and relationships, and the mutual responsibility between providers and users of services.

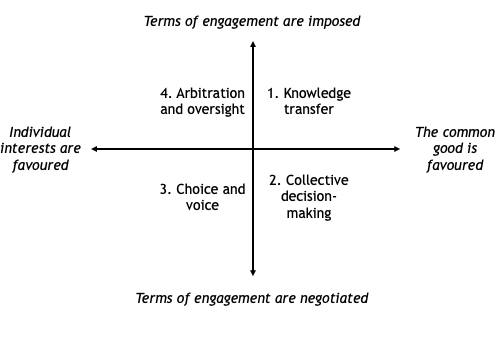

The scholar Rikki John Dean offers a different way of understanding models of citizen participation. He identifies two dimensions. The first asks whether we believe individuals will pursue their own interests (even the expense of others’), or strive for a common good. The second dimension asks who gets to set the terms of participation. Do those already in the more powerful position get to decide how others may participate, or can those participating negotiate the conditions of their participation as part of the process? These dimensions provide four broad types of participation, as illustrated below.

The first type assumes individuals will strive for a common good, but the terms of participation are imposed. Here, citizens views may be sought, but is for the purpose of better understanding population needs or pooling expertise, so that services can be made more efficient or effective within the prevailing system of management. Dean calls this type “knowledge transfer”.

The second type also relies on a logic of striving for a common good, but the rules of participation are not imposed. All decisions that affect people must involve them. This means each decision must be taken at the lowest (geographical) level possible (known as “subsidiarity”). Such egalitarian forms of public management are rare in the UK, but Dean gives examples from Brazil and Venezuela. Dean calls this type “collective decision making”.

The third type also says the rules of participation should not be imposed, but assumes each individual will pursue their own self-interest. This is where market-based mechanisms reside. Citizens are treated as consumers whose self-interest must be satisfied, and to whom those with decision-making power must ultimately respond. “The people are our bosses” as Boris Johnson said in his first speech as Prime Minister. Dean calls this “choice and voice”.

The fourth segment also assumes that each individual is likely to pursue their own interest, but returns to the idea that the rules of participation are imposed. This model relies on the arbitration of disputes when self-interest inevitably conflicts (just as ordinary citizens comprise a legal jury). It incorporates the idea of “oversight”, where decisions are given legitimacy by running them through a carefully-selected group of citizens in a tightly controlled process intended to provide reassurance that competing interests have been accounted for. Dean calls this type “arbitration and oversight”.

Doing participation

These frameworks – and there are lots of others – are helpful in demystifying the idea of “citizen participation” and helping us grasp the many different ways it might operate. But for public service and civil society leaders, they do not offer much by way of practical insights on how to go about doing citizen participation. That is something we at the GO Lab hope to explore over the coming months. This month, our outgoing 2020 Fellows of Practice will apply their diverse institutional and international perspectives to the practical side of citizen participation, and we will share their insights. We will explore the accountability question further in our “Motivation for Measurement” peer learning group. And we hope to bring this debate to the 2021 Social Outcomes Conference.

We would like your insights, too. What does citizen participation mean to you?