Relational contracting

This guide provides an introduction to relational contracting in the public sector, explaining what it is, the potential benefits and challenges, and how to adopt a relational approach.

Overview

6 minute read

Introducing relational contracting

There is increasing recognition that relationships are important to improving the delivery of public services and hence social outcomes. Practitioners have observed that a ‘transactional’ approach to contracting may not always be appropriate. Fortunately, an alternative – relational contracting – has been well-researched and applied in the private sector. However, there has been less work on its use in grants and contracts involving government or public bodies.

A contract, at its most basic level, describes the rules and norms that govern the relationship between two parties. Traditionally, contracts have tended to be framed as transactions, in which each party seeks to maximise their own interest at the expense of the other. To prevent this, lawyers have moved towards increasingly detailed contracts that try to cover every eventuality. However, in many cases, parties’ interests are aligned around the objectives of contract, and greater flexibility can help to adapt to unforeseen circumstances. By focusing on building and maintaining trust between the parties, a relational approach might sometimes be more effective in improving the outcomes of the contract.

Relational behaviours exist to some extent in all contracts. Many partners will naturally work relationally as a way to build and maintain high levels of trust, in order to ensure partnerships run smoothly and to minimise the risk of resorting to the courts. We call this relational practice, and it may occur regardless of the content of the formal contract.

However, partners may seek to be more deliberate about their relational practice, by making the building and maintenance of trust explicit in the written contract. Important features can be explicitly defined from the outset, which we call relational intent. This can be further strengthened when these relational behaviours are codified into principles that are enforceable by a court, becoming a formal relational contract or vested contract. In this guide, we are generally referring to the adoption of a greater relational intent within public contracts, whether legally enforceable or not.

When to take a relational approach

There are a number of circumstances which may lead public sector organisations and their partners to choose to be more deliberate in adopting a relational approach to contracting.

- Complexity. For many goods and services that organisations buy, it is relatively easy to specify the important features in the contract and verify whether they have been delivered, making them amenable to traditional, transactional contracts. However, other products and services are much more complex – such as delivering social support to a vulnerable population. Here, it can be difficult to specify exactly what is needed, how much it will cost and/or how to verify whether it has been delivered. As a result, contracts may need to be adapted along the way, and a relational contract can aid this process.

- Changeable environment. As well as changing understanding of the product or service itself, external forces may change the requirements of a service or the ability of a provider to deliver it at the expected cost. Prescriptive contractual terms can hamper the ability to alter the approach, making the relationship less resilient to external shocks (with Covid-19 being an extreme example). The broad principles enshrined in a relational contract can help to maintain focus on the overarching goals, rather than on the specific method of reaching them.

- Goal alignment. Traditionally, contracting is seen as an adversarial process, assuming the goals of the purchaser and the provider are different, and each will act in their own self-interest. However, often parties interests are relatively well-aligned, and this alignment can be strengthened through the contracting process. Relational contracting allows parties to acknowledge and leverage their mutual goals, while retaining some levers – reputation, the formal contract, and explicitly articulated shared principles – to back up trust.

- Mutual reliance. In order for a contract to be delivered effectively, collaboration is often required, recognising that parties may each need to bring certain skills and assets to the table. It may be difficult to specify or put a value on each party’s contribution up-front, but a relational contract allows the articulation of mechanisms for negotiation and decision making throughout delivery that can underpin a closer and more collaborative relationship.

The challenges to a relational approach

In certain circumstances, relational contracting may lead to a more effective contractual relationship. However, it is not always the most suitable approach. There are a range of challenges to overcome, particularly when one of the parties is a public body.

- Opportunism. In any contract, one party may seek to opportunistically advance their own interest at the expense of partners. Relational contracting seeks to limit the risk of opportunism by building trust, but it can also limit the ultimate recourse of litigation by making contractual terms less clearly enforceable.

- Scrutiny and corruption. Relational contracting can sometimes appear like improper collusion. This can complicate scrutiny of public contracts, making it harder to identify and protect against corruption. Even in the absence of actual corruption, the mere accusation of corruption can be used by third parties to undermine the contractual relationship.

- Restrictive procurement rules. Strict processes surrounding public procurement, enshrined in legislation and policy, aim to limit corruption and maximise value for money, reassuring taxpayers that their money is being well spent. However, the ways in which these rules are applied can make it harder to build trust-based, long-term relationships with a provider.

- Misunderstanding. While parties may ostensibly agree on a set of shared principles to govern a relational contract, judgement will be required in interpreting what they mean in practice. Depending on their organisational backgrounds and priorities, parties may come to very different conclusions about what those broad principles actually mean.

- Unequal power dynamics. Contracts are held between a range of different parties, and as a result, one party may have considerably more power than another. These power asymmetries exist in all contracts, but may be magnified in relational contracts, where greater flexibility and room for interpretation may be abused by the more powerful party.

- High up-front investment. The reduction in legal recourse which may accompany a relational contract may be particularly intolerable if one of the parties is required to make a large and specific investment in the service. In these circumstances, the provider needs to be reassured that its investment is protected if things go wrong.

- Transaction costs. A relational contract avoids the need to specify up-front every eventuality which may arise during a contract. However, there are still transaction costs associated with building trust before the start of the contract, and undergoing negotiations during delivery, which must be weighed against the benefits of a relational approach.

- Staff turnover. The trust which sustains relational contracts is grounded in personal relationships between individuals within each of the contracting organisations. The ongoing process of building and maintaining trust can therefore suffer setbacks if there are frequent or dramatic changes in key stakeholders.

How to adopt a relational approach

Adopting a relational approach to a contract may be appropriate if the benefits outweigh the challenges. This may happen organically, regardless of how the contract was designed, but there are a number of practices which embody relational intent, and hence can help to bring about a relational contract.

- A strong relationship. A successful relationship during contract delivery is much more likely if the parties have already built a productive relationship beforehand. This begins with market stewardship – contracting authorities should be aware of who can provide a particular service, and ensure they maintain positive relationships with those potential providers. When a particular service is required, a more focused relationship can be established. This can be achieved through procedural tools like a staged procurement process, which gradually narrows the field as a purchaser gets to know potential providers.

- Tightly defined goals. Flexibility in how goals are achieved is an important feature of relational contracts. However, what these goals are, and how their achievement will be verified, should be clearly articulated so all parties are pulling in the same direction. Both practitioner feedback and academic research suggests that a strong formal contract helps to set the tone of the relationship and thus supports relational working during delivery.

- Shared principles. To help keep parties on the same page over the course of the contract, they may agree to abide by a set of shared principles. These principles are explicitly articulated in the contractual documentation. They dictate the values and behaviours that will guide how the organisations will interact with one another, such as reciprocity, autonomy, honesty, loyalty, equity and integrity. If parties adhere to their shared principles, the scope for conflict should be minimised. Where it does arise, principles provide a framework to address grievances.

- A suitable procurement procedure. Public procurement processes can sometimes act as a barrier to many of the practices that help to unlock the benefits of relational contracting. Pre-award collaboration can seem to cut against principles of fair and open competition. However, some procurement regimes, such as the EU’s ‘Light Touch Regime’, may allow for more flexibility, acknowledging that competition is not always the best route to public value. Regardless of the procedure chosen, the tender process itself can be used to identify a provider’s propensity to relational working.

- A risk-sharing mechanism. Contracts provide a way of sharing various kinds of risk between the parties. Some risks can be anticipated, and how they will be shared can be specified upfront. Others cannot be anticipated, and a relational contract may therefore stipulate a governance mechanism to deal with risks as they arise. In addition, the payment mechanism of a contract may facilitate the management of financial and delivery risks, by aligning the purchaser and provider around a set of verifiable goals.

- A decision-making structure. Relational contracting anticipates changes to the terms of engagement between parties during delivery to deal with uncertainty and capitalise on collaboration opportunities. However, to unlock the benefits, ongoing communication is essential to facilitate negotiations. Doing so effectively requires clearly agreed forums and processes for communication, negotiation and decision-making from the outset.

Introducing relational contracting

6 minute read

When someone mentions contracting, it conjures up the image of a lengthy written document that two parties sign when undergoing a financial transaction, such as the purchase of services. Indeed, many contracts are written, and many are long: the famed wad of paper that goes in the bottom drawer, to be consulted only when things go wrong. But actually any transaction – indeed, any relationship, whether financial or not – is governed by certain rules and norms that the parties explicitly or implicitly sign up to. At its most basic level, a contract describes what these are.

Still, in describing relationships between organisations – especially financial ones – some sort of written agreement is to be expected, even if it is as simple as a letter or basic grant agreement. If a dispute arises, the parties are likely to make an effort to negotiate. Formal contracts are distinct in that they provide each party with extra protection by delegating a court of law to adjudicate if the parties cannot resolve the matter between themselves.

Knowing this, the parties to a contract might behave in ways that minimise the chance of a dispute occurring in the first place, by seeking to build a trusting relationship with one another. Stewart Macaulay, one of the first to observe and name ‘relational contracting’ in the mid-twentieth century, famously quoted a contract manager who stated that, “You can settle any dispute if you keep the lawyers and accountants out of it" (Macaulay 1963, p. 61). These ‘relational’ behaviours are present to some degree in all contracts. Relational contracts make these familiar features of contractual relationships more prominent. Most people recognise that a higher level of trust between the partners should help to make sure partnerships run as intended, and might reduce the threat of termination, arbitration or court. Many partners will naturally work relationally as a way to build and maintain high levels of trust. We call this relational practice, and it may occur regardless of the content of the formal contract.

However, partners may seek to be deliberate about their relational practice, by making the building and maintenance of trust explicit in the written contract itself. Important features of relational contracts, such as shared goals, principles, and decision-making processes, can be explicitly defined from the outset (although these may not be legally enforcable), which we call relational intent. Various authors, such as the academics Brown, Potoski and Van Slyke (2018) have argued that these kinds of features can help to build the trust which sustains relational contracts.

Finally, when these relational behaviours are codified into principles that are enforceable by a court, it becomes a formal relational contract. This approach was set out by academics David Frydlinger, Oliver Hart and Kate Vitasek in a widely-read 2019 HBR article called “a new approach to contracts”, in which they argue that the shared goals, principles and processes of relational intent can be made formal and enforceable. These authors and others have referred to this type of enforceable relational contract as “a vested contract” (Vested Outsourcing, 2022) because each partner is vested in the others’ success.

Throughout this guide, we are generally referring to the adoption of a greater relational intent within public contracts, whether legally enforceable or not. Where we are specifically discussing features of formal relational contracts, where relational features are intended to be legally enforceable, we refer to them as such. However, as we discuss below, the efforts to build and maintain trust that are at the heart of a relational approach to contracting often do so with the intention of avoiding a legal dispute. As we will explain, there are many ways to encourage trust-building behaviours after a contract has been signed, during the delivery of the service. Relational contracting, as with any relationship, demands ongoing effort on the part of the people involved to make it work.

Building and maintaining trust

In a typical marketplace, we tend to assume that buyers and suppliers’ goals are not aligned: buyers want to obtain the highest quality at the cheapest price, and suppliers want to maximise their profit (I.e. the difference between the cost to them of supplying something, and the price they get paid for it). Sometimes, though, there seems to be a natural alignment: for example, both governments and non-profit organisations may have an interest in improving social outcomes for disadvantaged groups. But even in cases like that, perfect alignment of interests is rare. A non-profit may narrowly promote the interests of a particular group, whereas governments need to balance the interests of everyone. Therefore a key risk in any financial transaction, be it a grant or a contract, is that one party tries to further their own advantage at the expense of the other. For example, a provider could exploit a purchaser or funder’s lack of understanding of the true cost of a service to make outsize profits / surplus. A purchaser could withhold key information that a provider requires in order to favour their own in-house provision. Mutual trust between the parties can help to insure against parties exploiting these so-called ‘information asymmetries’. But trust does not pre-exist – it needs to be built, nurtured and maintained. To some extent, this will naturally happen as the parties ‘get to know each other’ over time. But there are also natural incentives to building and maintaining trust that the parties to a contract can make use of to maximise the chances of a win-win outcome.

Buyers and suppliers both need to negotiate agreeable contract clauses, and neither side wants the other to flout these after signing

Parties have an incentive to negotiate contract terms that are favourable to both sides at the outset, to maximise the chance that a deal gets done. They also both have an incentive to ensure that their partner adheres to these terms (hence the threat of third-party arbitration or court if they do not). Formal relational contracts take this a step further by including clauses that outline broad shared principles that are intended to encourage pro-social behaviour, such as prompt and open communication of issues, adapting to changing circumstances and a commitment to sharing risk and reward. Theoretically, these principles might be enforceable in court, giving the parties recourse should the feel their partner is not adhering to them – though the degree to which they can truly be adjudicated varies with jurisdiction and is a matter of some debate.

Suppliers don’t want to lose future business; purchasers may not want the cost of switching suppliers

Providers will generally have a desire to win future business from the purchaser, and will be aware of the risk of opportunities being lost if they misbehave. Equally, the buyer may wish to avoid the cost and effort of disputing and reprocuring a service. These forces create an incentive on each side to maintain a positive relationship. A relational contract can make explicit the expectation that a relationship will continue as long as both parties are getting good value.

Suppliers and purchasers both want to maintain a positive reputation among third parties

If the potential for future contracts is an internal feature of the relationship, then its external counterpart is reputation. Parties to a contract will be seeking to engage in future contracts with different organisations: purchasers will have to buy other services, while service providers will seek to offer their services to other purchasers. As a result, how they are perceived to behave in contractual relationships – their reputation – is crucial to their future success. If a party takes advantage of another, and this is made public, its reputation is harmed. Again, the incentive works on both sides. Suppliers do not wish to gain a reputation for taking advantage of their clients as this could deter other buyers who may give them future business. Equally, buyers do not wish gain a reputation for abusing their power which might deter other providers from working with them.

Traditional contracts tend to include confidentiality clauses that prevent the parties from making any missteps public. This can reduce the power of the reputational mechanism. Transparency helps to ensure this mechanism works effectively, and can be an effective tool in a relational contract.

The same two organisations may have multiple contracts between them

Finally, if two organisations have multiple contracts, then misbehaviour by either party in one might affect the relationship across others. This raises the stakes, and helps to create an incentive with both parties to build and maintain trust.

Public relational contracting

There remains a particular dimension to the scope of relational contracting that we will discuss in this guide. The vast majority of research and practice in relational contracting focuses on contracts between companies in the private sector (such as within manufacturing supply chains). But when it comes to efforts to improve social outcomes or develop public goods, a government body is very often party to the contract – whether a local agency, national government or supra-national organisation.

This introduces added complications. Public contracts are bound by an extra set of principles, often codified in law, that private contracts are not subject to in the same way. Fairness, transparency and value for money all take on additional importance when taxpayers’ money is involved in the exchange. Where the features of relational contracting clash with these principles, it may create tension. Alongside the benefits, we will examine some of the potential barriers to relational contracting, many of which relate to the unique nature of public contracting.

In early 2020, governments worldwide instituted restrictions to reduce the spread of COVID-19. The effect of this on social service providers working with vulnerable populations was that the limitations on social contact meant they were unable to deliver their interventions as intended. That made it hard to achieve the desired outcomes.

A 2021 paper by FitzGerald et al. explored how this affected 31 social services contracted under the UK Government’s Life Chances Fund. This £70m fund contributed up to 50% of the price of contracts aimed at improving social outcomes for people experiencing various forms of social disadvantage, with a local public body paying the rest. The UK government stipulated that all contracts receiving money from this fund must be ‘social impact bonds’, a type of public contract that uses a payment-by-results mechanism linked to social investment.

The Life Chances Fund’s aims did not explicitly require or anticipate a relational approach. Yet parties’ behaviour during the crisis suggested that many had adopted one. None reached for emergency clauses such as force majeure that may have released them from or alleviated contractual obligations. All providers who had already launched services adapted them rapidly to accommodate the new reality. Importantly, they could do so easily with minimum consultation with over-stretched government colleagues because of the nature of the ‘social impact bond’ contract. These contracts usually specify the end outcomes to be achieved but are intentionally flexible on the details of the service. There was also some flexibility shown in the payment terms of the contract – 21 of the 31 projects temporarily switched to a different arrangement – suggesting that the relationships between purchaser and provider were strong enough for this to be done on trust, at short notice and with minimal paperwork.

Of course, the Life Chances Fund experience is not unique - thousands of organisations all over the world acted in similar ways – but it provides a good example of the value of relational practice when crisis hits.

When to take a relational approach

5 minute read

What might lead public sector organisations and their partners to choose to adopt a relational approach to contracting? The following section lays out some of the circumstances which may justify the use of relational contracts:

- The product/service is complex: the required service is hard to specify up-front because it is innovative or because the needs are constantly changing, so contract terms will need to adapt accordingly. We call this complexity.

- The external environment is changeable: external forces are unpredictable and the partners need to ensure the relationship can withstand changes. We call this changeable environment.

- The partners’ goals are aligned: partners perceive that their interests are closely aligned at the outset and wish their formal partnership to reflect that. We call this goal alignment.

- The partners will rely on each other during delivery: partners expect to collaborate closely in the delivery of a service as they each have skills and assets to bring to the table. We call this mutual reliance.

Complexity – the need to contract for a complex product or service

Many goods and services that organisations might purchase, like office supplies or landscaping services, are relatively easily specified in the contract. The important features of the product – the type, colour and number of pens, or the frequency of watering, weeding and pruning flowerbeds – are relatively straightforward to specify upfront, and it is relatively easy to verify whether they have been delivered. As a result, these kinds of ‘simple’ products are amenable to traditional, transactional contracting.

However, other products are much more complex. Complex products or services are characterised by the difficulty of specifying upfront exactly what is needed, exactly what it will cost to deliver it, and/or exactly how to verify whether it has been provided to a satisfactory standard. This uncertainty could be caused by the requirement to develop new innovations in a product / service, or because the product / service interacts with a set of external factors beyond either party’s control.

In their 2018 article, Complex Contracting: Management Challenges and Solutions, the academics Trevor L. Brown, Matthew Potoski, and David M. Van Slyke make the case for adopting a different approach to contracting for complex products. They suggest the need to craft “win-win” rules, which incentivise cooperation between parties. By sharing decision-making, as well as the risks and rewards of the contract, parties can all buy into the relationship and feel they have an interest in its success. Over time, trust can be built between parties, especially if forums are provided to resolve issues and develop mutual understanding. All of these features of relational contracts can help to better navigate the challenges associated with contracting for complex products, through a spirit of collaboration and flexibility.

Changeable environment – ensuring a partnership can withstand the unexpected

The need for resilience in public services has been brought into sharp relief over the last few years, as the Covid-19 pandemic placed severe strain on social services, public finances, and the lives of vulnerable service users. When things change, services must be able to respond. But if the contract governing a service lacks flexibility, providers may be unable to adapt to changing circumstances, ultimately leading to poorer outcomes for service users.

However, even outside times of crisis, external circumstances are not always predictable and adaptability may need to be built into contracts up-front. In social services, for example, if the needs of the population change during the contract, it is likely that some important aspects of the service will need to be altered during delivery. Some features that were specified may be redundant, or even counterproductive, while other features that were not included in the original contract may turn out to be vital to the effective delivery of the service. As in crisis response, these changes may be hamstrung by an overly prescriptive contract.

In this regard, relational contracts can be more accommodating than traditional, transactional approaches. Adopting broad principles rather than detailed terms ensures the focus of the contract remains on its overarching goals, rather than on the predicted path to those goals before the contract started. If some of those assumptions prove false, or conditions change so that they no longer hold, then a relational contract can be adapted within the bounds of its principles and objectives.

Goal alignment – taking advantage of common interests

Traditionally, contracting is seen as an adversarial process, with each party seeking to maximise the benefit to itself. Strict rules are required in the contract to give each side assurance that they will not be exploited by the other. However, relational contracting promises a different way of doing things, based on cooperation for mutual benefit.

Transactional approaches to public contracting tend to align with agency theory, which assumes the goals of the principal (the purchaser, e.g. a public body) and agent (the provider) are different. Agents will pursue their own self-interest, behaving opportunistically and taking advantage of additional information they possess, at the expense of the goals of the principal. As a result, principals should not trust agents, and must use incentives and sanctions to correct their behaviour and achieve goal alignment. Accordingly, providers are not to be trusted, and so a strong, specified contract is required to ensure the objectives of provider and commissioner are aligned.

A competing theory – that of stewardship – assumes the goals of the principal and steward (provider) are broadly aligned, and providers are motivated by these shared goals more than self-interest. Principals can start from a position of trust in stewards, and empower them through responsibility and autonomy to deliver common goals. In the case of many public services, particularly those aimed at helping vulnerable groups that involve charity providers, it might seem reasonable to assume that their high-level goals are broadly aligned with the objectives of government – to improve the lives of their service users.

But stewardship seems to go too far in the opposite direction to agency theory. Even if most providers could be trusted to consistently set aside their self-interest in favour of the interests of the partnership, some could not. That means the blind trust of stewardship will generally represent an intolerable risk to governments responsible for public money and the reputational consequences if things go wrong. In a 2007 paper, David Van Slyke analyses social service contracting at the state and county level in New York and finds that neither theory fully captures public sector contracting practice, which in reality reflects a more negotiated, gradual development of trust. He suggests that a third option, relational contracting, might offer a better account of the realities of public sector contracting.

In relational contracting, trust is a key component of the relationship, but it is backed up by other levers: reputation, the formal contract, and explicitly articulated shared principles. These principles can be actively co-developed during the contract development process, hopefully promoting greater buy-in, rather than assuming that parties’ interests will be aligned by default. As a result, parties can build a more collaborative partnership than that of agency, whilst also mitigating some of the risks associated with stewardship.

Mutual reliance – the expectation of close working between the partners

Sometimes partners may recognise that they each have important skills and assets to bring to partnership. At its most basic level, a contract is born when one party needs something it does not have (and cannot easily produce itself) so buys it from another. In many cases, though, a purchaser needs to bring more than money to the table – they may have other assets critical to success such as key relationships, convening power with other stakeholders, data, or technical know-how. In such cases, the parties may need to collaborate in order for the contract to be delivered effectively.

As with complex products, it may be difficult to specify up-front exactly how this collaboration will work. The potential for mis-steps, where there is confusion or disagreement over who has responsibility for certain actions or who should absorb a particular cost or risk, is high. As such, articulating mechanisms for negotiating throughout delivery can help to underpin a closer and more collaborative relationship between partners.

Embedding this collaborative approach in the contract can also make relational contracts better at enabling parties to respond to changes during delivery, such as unforeseen challenges during service delivery, changes in what needs to be delivered, or changes in the broader context.

Kirklees council, a municipal government in the North of England, has been contracting support services for vulnerable adults for around two decades. This cohort of service users experience multiple and compound disadvantage and are understood to need support to overcome homelessness, substance misuse, mental health problems and unemployment. Serving this diverse group is a good example of uncertainty – it is hard to know upfront how many people will need support, or what support they will need, and for how long. Prior to 2019, the council held 15 contracts with 9 different organisations to deliver support services to this group. By 2019, there were questions about the quality of services and the degree to which provision was meaningfully supporting service users. Providers faced constant uncertainty about whether the programme would continue to be funded – but then received automatic extensions without competitive pressure. In the meantime they were left to get on with things provided they did what the contract said. This was not always the same as doing what the service users actually needed. Some providers competed to work with service users so as to meet these utilisation targets, rather than collaborating to meet a broad range of intersecting needs.

Recognising these issues, the council explored a different approach, which led in September 2019 to the launch of a new service that brought all the providers under a single contract managed by a newly-formed entity called Kirklees Better Outcomes Partnership. It did not include a detailed specification of the length and intensity of support to be provided to service users. Instead, payment was tied to providing proof of positive social outcomes that that people on the cohort could achieve, according to pre-agreed metrics: sustained accommodation; education and qualifications; employment; volunteering; engagement with drug and alcohol services; stability and wellbeing. This allowed greater flexibility to adapt to service user needs that are varied and ever-changing. The job of managing multiple providers was given to the newly formed entity who also operated a single referral system, enhancing collaboration and goal alignment.

Read the GO Lab’s evaluation reports of Kirklees (Rosenbach and Carter 2020) on gov.uk. See also Carter et al. (forthcoming).

A similar model for a similar cohort of adults was launched at a similar time in another UK local authority, Plymouth. But rather than use an outcome-based payment mechanism and a single newly formed entity to try to unlock the benefits of relational practice, it relied on different tools: shared governance guided by a set of ‘principles’. The contract is comparatively long (10 years with break clauses), and includes seven providers and multiple sub-contractors. The CEOs of the seven providers, alongside three council commissioners, comprise a 10-member decision-making body who control the annual budget of £7.7m. The body can only make decisions unanimously, and does so with reference to a set of ‘alliance principles’ enshrined in the contract, as follows:

- to assume collective responsibility for all of the risks involved in providing services under this Agreement;

- to make decisions on a ‘Best for People using Services’ basis;

- to commit to unanimous, principle and value based-decision making on all key issues;

- to adopt a culture of 'no fault, no blame' between the Alliance Participants and to seek to avoid all disputes and litigation (except in very limited cases of wilful default);

- to adopt open book accounting and transparency in all matters;

- to appoint and select key roles on a best person basis; and

- to act in accordance with the Alliance Values and Behaviours at all times.

It took four years prior to contract launch for the relationships between the organisations and the council to mature to the point where such shared risk and decision-making could be enshrined in a contract. The only organisation to have left the alliance so far (due to discomfort with the financial principles) joined the process much later than the others.

Thanks to Gary Wallace and the Plymouth Alliance

The challenges to a relational approach

8 minute read

The previous section presented some of the theoretical and practical justifications for adopting a relational approach to contracting. But as those justifications illustrate, it is not always the most suitable approach. In fact, some argue that relational contracting is not appropriate for public contracts at all. In this section, we explore some of the concerns surrounding relational contracting, particularly when one of the parties is a public body or government entity. While not necessarily insurmountable, these challenges ought to be considered and addressed by organisations seeking to pursue a more relational approach to their contracts.

- Opportunism: the risk that one party may take advantage of ‘loose’ contract terms for their own (unfair) benefit.

- Scrutiny and corruption: close relationships and flexible contract terms can make scrutiny difficult and increase the risk of nefarious practice.

- Restrictive procurement rules: highly rule-bound or ‘open market’ procurement procedures tend to favour a transactional approach.

- Misunderstanding: broadly-scoped contract terms might increase the chance of misunderstanding which could lead to conflict.

- Unequal power dynamics: weakened legal protections can make the contract risky for the smaller party.

- High up-front investment: when a large upfront investment is required of a provider in assets that cannot easily be repurposed, the protection of a more rigid contract may be essential.

- Cost: building and maintaining a high-intensity relationship drives up costs on both sides (which may or may not be justified by the benefits).

- Staff turnover: the personal relationships which drive trust may dissipate due to staff turnover or political change.

Opportunism – are the consequences intolerable if a partner breaches trust?

The emphasis on trust in relational contracting can paint an optimistic picture of the world, where everyone’s interests are aligned in pursuit of a set of overarching goals. Even if everyone is genuinely interested in pursuing those objectives, they also likely have other, competing goals that may at times take precedence, at the expense of the goals of the contract. All contracts, private or public, are at risk of opportunism from one of the parties taking advantage of their additional knowledge of an area of the contract, in order to further their own interests.

Relational contracting is partly a response to the risk of providers opportunistically taking advantage of one another. It emphasises trust-building mechanisms, rather than relying on the transfer of risk and threat of litigation, which is the ultimate recourse in a conventional contract should one party misbehave. But by relying more on trust, a relational contract can weaken those protections by making certain contractual terms vaguer or less enforceable. While emphasising trust is explicitly intended to make opportunism and conflict less likely, it also means that if those things do occur, the consequences for one or both parties can be more serious.

Scrutiny and corruption – would it be harder to subject the contracting relationship to external scrutiny?

Relational contracting can complicate scrutiny of public contracts, making it more difficult to identify and protect against corrupt practice. Many of the guardrails that protect against corruption are fundamentally about making it harder for parties to develop excessively close relationships that could lead to collusion: think of requirements for arms-length legal principles, open-market tender processes and transparency in public life. Relational contracts emphasise a close relationship from the start and allow flexibility by design. This appears to cut against some of the protection from corruption and thus relational contracting might seem to increase the risk of it.

Indeed, there is some evidence that flexibility can be manipulated for private advantage: in a 2020 paper, the researchers Jonathan Brogaard, Matthew Denes and Ran Duchin analysed $2.3tn-worth of contracts awarded by the US federal government to the private sector between 2001 and 2012. They found that “politically connected firms were three times more likely to successfully negotiate for contract improvements after winning a contract” and “in anticipation of successfully renegotiating contracts, [politically] connected firms submitted bids that were, on average, 5.4% lower than those of unconnected firms”.

Strong governance with a clear process for decision-making under the contract is an important feature of relational contracting that can help a contract retain its resilience against impropriety amongst any individuals involved.

However, even in the absence of actual corruption, the accusation of corruption, even if unfounded, can also be used to undermine a contractual relationship by third-party opponents. For example, a mayoral candidate might wish to show that the incumbent gives private providers an easy ride. Of course, public scrutiny of public contracts has an important function in limiting the potential for public corruption, so accusations of corruption, if well-founded, should not be discouraged. But this poses a particular threat to relational contracts, where the defining feature of having close, trust-based collaboration can appear to be evidence of improper collusion. In a 2008 working paper, Pablo Spiller of the University of California, Berkeley suggests that this threat of third party attack on public contracts leads to increasingly tight specification, which in turn limits the scope for more relational approaches to public contracting. In 2021, Beuve, Moszoro and Spiller showed that the effect of tighter specification is a higher rate of renegotiation in public contracts, as the specifications are not fit for purpose.

Procurement – do restrictive rules make close partnership working too difficult?

Public procurement rules provide another guardrail against misuse of public money. In many countries, public procurement is subject to various requirements focused on providing for open, fair competition between potential providers, with the aim of limiting corruption and maximising value for money. Strict processes enshrined in procurement legislation and policy aim to limit the scope for malpractice and give confidence to the public that their money is being well (or at least fairly and transparently) spent.

However, these well-intentioned rules can limit the scope for public relational contracting. As noted above, what to the relationalist are features of productive collaboration can to others look like impropriety, and so public procurement rules can often cut against them. For example:

- Rules can limit the scope for developing a relationship of trust with potential bidders for a contract prior to a tender process being launched, as it might appear that some bidders are being unfairly favoured in the contract award process.

- It is often hard (though not impossible) for an organisation involved in designing a contract to subsequently bid to deliver it, meaning the investment in the relationship on both sides during the design phase is wasted.

- Procurement rules might limit the scope for re-contracting the same provider unless they are successful again in an open competition. This means that incumbent providers have less incentive to maintain a productive relationship with the contracting authority during delivery. As one commissioner put it, “It’s a bit like saying you’ve got a plumber who completely stuffed up your bathroom last month, but the procurement process has told you you’ve got to have him again.” (Quoted from Liam Sloan’s 2018 research, p26, available on request).

As we discuss in the next section, many of these issues derive not from the procurement rules themselves, but from a rigid and risk-averse interpretation of them by those who oversee contract award processes. It is possible to find ways to develop more relational practices within the limits of procurement regulations, but this poses an additional challenge to those hoping to develop public relational contracts.

Misunderstanding – is the scope for misinterpretation high?

Relational contracts may include “a commitment to shared principles” intended to help the parties navigate uncertainty – for example, a commitment to putting the service user at the heart of all decisions, or a commitment to share risks according to whichever of the parties is best placed to manage them. Where there is a lack of formal terms to guide the response of parties to a particular situation, being on the same page about the basis for decision making makes it easier to agree on a course of action.

But this is quite a big assumption, not least because while parties may believe they agree on a set of principles, their respective organisational backgrounds and priorities can have a significant influence on how they interpret what those broad principles actually mean. While they might ostensibly agree on a set of principles, judgment will be required in interpreting what they mean in practice. For example, what does “putting the service user at the heart” mean when it comes to striking the right balance between number of people served and the intensity of service provided to each? Unless accompanied by some specific stipulations, such vagueness can provoke disputes that work against a productive relationship.

Power – does one party have considerably more unchecked power than the other?

The challenges of organisational differences can be further exacerbated by the asymmetries of power that exist between different organisations who are party to a contract. Contracts are held between a range of different parties, from different sectors and of different sizes. This means there can be a large difference in the power each party holds in a contract. A small, local non-profit provider organisation has less power than the government organisation commissioning them to deliver a service. That generally doesn’t matter when things are going well and the parties are in agreement, but can cause problems when parties do not agree about something.

Of course, power imbalances are often built into transactional contracts. A dominant party can dictate favourable terms in both the initial contract and subsequent renegotiations. They also tend to have greater resources, allowing them to expend more on legal support. However, the contract as written, and the legal system which underpins it, provides a level of protection to weaker parties. If a contract stipulates something must not happen, and it happens, then the aggrieved party technically has a means of legal recourse, even if they are the less powerful organisation.

In relational contracts, however, the power imbalances may be magnified. With broad principals replacing detailed specification, much more may be open to interpretation, allowing the party with the greater financial (and therefore legal) muscle to shift more risk onto the junior partner(s). The added flexibility of relational contracts, in many cases a benefit to their use, may become a problem if it is abused.

In his 2008 paper referenced earlier, Pablo Spiller of the University of California, Berkeley, points out an additional dimension of the power relationship in public contracts. Government, unlike private actors, has much greater power to affect the way a contract works by altering the rules of the game, either through legislation that circumvents the contract terms, or more subtle administrative processes like regulatory action. Government opportunism is mitigated by institutional limits on government power, like the rule of law. In some contexts, therefore, it may not be a major factor in relational contracting decisions; in others, where institutional limits on the powers exerted by government are much weaker, it may pose a grave concern to parties to any kind of contract, but especially to relational ones.

Investment – is one party required to make a high upfront investment in the service?

As discussed, relational contracts can reduce the legal recourse for a party if its partner engages in opportunistic practice. This is particularly intolerable if one of the parties has been required to make a large up-front investment in the service in an asset that cannot easily be used by the company elsewhere in its operations – for example, training a workforce for a service-specific accreditation. While the additional flexibility and closer working relationship of a relational contract may still be useful in such circumstances, the provider still needs to know that its investment is protected even if things go wrong. A more tightly-specified, traditional contract may therefore be required.

Transaction costs – is the additional cost of developing and maintaining trust justifiable?

In the complete absence of trust, two parties to a contract would need to try to anticipate every single contingency that might occur during the course of delivering a contract, and what action would be taken. When the product or service is complex, innovative, or operating in a rapidly changing external context, that is practically impossible – which is where a relational contract might come into its own. Using a relational contract is more practical than trying to negotiate every possibility up-front, and may mitigate the risk of a ‘hold up’ or blockage down the line. But there is still a considerable cost to both parties of investing in trust-building prior to and during a contract start, and undergoing continual negotiations during a contract. These ‘transaction costs’ need to be weighed against the benefits of contracting relationally – something researchers from the GO Lab have referred to as “walking the contractual tightrope” (FitzGerald et al. 2019).

Staff turnover – how will changes in personnel impact upon the relationship?

The trust which sustains relational contracts is grounded in personal relationships between individuals within each of the contracting organisations. Turnover in these key individuals can therefore have a significant impact on the success of the contract. Codifying the terms of the relationship in principles and processes as part of the contract may go some way to mitigating this risk. However, as we have discussed, building and maintaining trust is an ongoing process, and one that may suffer setbacks if there are frequent or dramatic changes in key stakeholders. This issue may be particularly pertinent in public relational contracts, where political developments can lead to a wholesale change in leadership overnight, and with it the potential for significant changes in policy direction and approach. Formal relational contracts (or vested contracts), which are ostensibly enforceable in court (though this varies by jurisdiction), were developed in direct response to this issue: they aim to provide legal recourse for a breach of ‘relational’ terms if there's a ‘new sheriff in town’ (see Frydlinger et al. 2021, “Contracting in the New Economy”, p. 201-204).

Here, we give two brief examples of public contracting arrangements that have not concluded as anticipated at the outset. These are not intended to be cautionary tales against relational practice, but rather, they illustrate that all contracts are susceptible to some degree to the challenges listed above. A public contract going wrong does not always mean court cases, public inquiries or high-profile news stories. Often the parties renegotiate – a 2021 study by Jean Beuve and Stéphane Saussier of Sorbonne University looked at the rate of renegotiations in public contracts in a range of fields worldwide and found it was almost always over 50%, and often much higher. (Of course, renegotiation does not always mean things have gone wrong – this could be a form of relational working, albeit an inefficient one). If the parties do part ways, they are likely to do so quietly to minimise reputational fall-out.

Social Impact Bonds (SIBs) are a type of payment-by-results contract for social services backed up by third-party social investment. The first ever one of these – which aimed to reduce re-offending amongst ex-offenders leaving Peterborough Prison in the UK – was stopped early due to a policy change in central government (Disley et al. 2015). So was another early SIB in the UK, the Adoption Bond, IAAM (Anastasiu and Ball 2018). These are both examples of the risk of a major power imbalance in the relationship – in this case, government changed the rules and scuppered the contract. In both cases, third-party investors had financed the up-front cost of the services in anticipation of their success.

Government can also unduly favour partners. In another UK example, a charity called Kids Company was repeatedly given large grants by central government to fund its programmes. The charity’s well-known founder, Camila Batmanghelidjh, had built up a strong trusting relationship with several government ministers, including the prime minister. The lack of contract-like provisions in the funding arrangements meant a total reliance on these relationships of trust. Officials across government became increasingly concerned with how the money was being used, and the charity closed in 2015 due to financial difficulties despite being given a £3m emergency grant from government that year. The closure was subject to a government inquiry (Charity Commission 2022).

There are hazards too in being overly transactional. Many governments around the world provide job-seeking support to the unemployed. A large challenge with this is that there is always high uncertainty about both how much support the unemployed will need (are they long-term unemployed or just going through a rough patch?), and how many job openings are available to them (which is dictated by prevailing economic conditions). Many governments have sought to push the risks of this uncertainty onto providers by using payment-by-results. Providers are paid only when an individual they worked with becomes employed. Research in 2015 by Eleanor Carter and Adam Whitworth shows that since providers cannot control the needs of the cohort of unemployed or the prevailing labour market conditions any more than the government purchaser can, they manage the uncertainty and risk by cutting costs and choosing to work with individuals closest to the labour market already. This is a rational response to the incentives in the contract, but may not be what the government purchaser intended. It suggests a more relational approach might do a better job of aligning the goals of purchaser and provider.

How to adopt a relational approach

8 minute read

The previous sections show that relational approaches to contracting provide a range of possible benefits, but also some potential pitfalls, and so is only suitable in circumstances where the benefits outweigh the pitfalls. Often, a relational approach will emerge in a contract regardless of how it was designed, as a natural result of parties getting to know one another and working together to resolve issues. Viewed this way, a relational contract is an ongoing process, not a one-off signing of a lengthy document. However, the chances of such productive collaboration occurring can be greatly enhanced if the contract is designed with a relational approach in mind. When, on balance, circumstances recommend a relational contract, certain practices can help to bring it into being. This section outlines some of these practices, to give a practical flavour of what it takes to undertake relational contracting for those who may be engaged in it, or considering it.

- A strong relationship

- Tightly defined goals

- Shared principles

- A suitable procurement procedure

- A risk-sharing mechanism

- A decision-making structure

A strong relationship: a long-term investment in the relationship prior to contract drafting and signing

While it may sound obvious, a successful relationship during contract delivery is much more likely if the parties have built a productive relationship prior to delivery. This is particularly true in many public contracting situations, where procurement regulations mean a great deal more emphasis is placed on the tendering and selection stages of a partnership than on the delivery stage. Good ‘market stewardship’ is an important part of this – a contracting authority should know who is the market to provide a particular service, and should put a premium on its positive relationship with those providers.

Investing in a relationship informally, before any deal has been done, can be expensive and risky for both parties. It can also be made difficult by due process which emphasises fairness and transparency. There are ways to overcome these obstacles procedurally, such as through a staged procurement process, that starts with an open call and gradually narrows the field as the purchaser gets to know potential providers. The current European Union procurement framework enables such practices through a range of mechanisms, though they remain rare due to a risk-averse culture amongst procurement professionals (see below).

Tightly defined goals that provide clarity on what success looks like, with flexibility on how to achieve it

Flexibility during delivery is a key benefit of a relational approach to contracting. This often requires a loose and adaptable specification of what exactly is to be provided. However, the end outcomes desired, and how these will be verified, should be made absolutely clear in the contract, so that all parties pull in the same direction. Vagueness about what success looks like and, particularly, on how to tell if has been achieved, can actually work against a positive relationship, as the lack of a standard yardstick upon which to evaluate success leads to conflicts of interpretation. Like other aspects of the contract, the parties could include mechanisms to mutually agree on changes to the definition of success during delivery, should circumstances demand it.

Some evidence even suggests that a strong service specification, rather than undermining flexibility and increasing the chance of conflict, can support relational practice. For example, in a study of government childcare services in Ohio, Amirkhanyan, Kim and Lambright (2012) find a positive association between contract specificity and relational character: as contract specification increases, contracting relationships become stronger, measured by features like goal alignment and cooperation in implementation.

Many practitioners agree that a strong formal contract helps to set the tone for the relationship, meaning that clear responsibilities and expectations can lead to more positive interactions in areas with more ambiguity. However, there are drawbacks. In a 2008 paper, Elisabetta Iossa and Giancarlo Spagnolo showed that a tight contract can support relational practice – but if this does not work, the contract becomes extremely transactional. It can also increase the likelihood that a contract will need to be renegotiated, which is expensive and can favour parties with more resources to renegotiate to their advantage.

Shared principles, explicitly stated in the written contract documentation

Shared principles form a key part of a relational contract. The parties agree to abide by a set of values for partnership, dictating the overarching aims of the collaboration and the way in which organisations will behave and interact with one another. In their widely-read article published in Harvard Business Review in 2019, relational contracting experts David Frydlinger, Oliver Hart and Kate Vitasek articulate six principles which parties should commit to in order to guide the terms of the relationship and avoid a breakdown. These are:

The authors argue that if both parties adhere to these principles, the scope for conflict ought to be minimised. When parties do come into disagreement, the principles provide a framework through which to address grievances. And ultimately, in the case of a ‘formal relational contract’, principles would form the basis for judicial intervention, with the courts being asked to interpret whether a particular principle had been breached by a party’s actions. As mentioned earlier, whether principles are really enforceable in this way is the subject of debate, and may depend on the legal traditions of a particular country or context.

A suitable procurement process that makes the most of flexibility allowed within the rules

As mentioned earlier, public procurement processes can appear to be a barrier to a lot of the other practices that unlock the benefits of relational contracting. Evidence suggests a relational contract is more likely to succeed if the parties have built a strong relationship before a service is launched, working together to design both the service and a ‘way of working’ together. Bajari et al. (2009) find that negotiation may be preferable to open competition for awarding contracts “when projects are complex, contractual design is incomplete, and there are few available bidders”. And Coviello et al. (2018) suggest more restricted competition between pre-selected providers may improve relational practice (and procurement outcomes). But such collaboration with a supplier prior to a contract being tendered and awarded can narrow the field of competition and give an advantage to a certain supplier. That seems to cut against the public procurement principle of fair and open competition.

One imperfect solution to this is to run two competitions – one for service design, and another for delivery. Even if the organisation who wins the design phase does not win the delivery phase, they have at least been compensated for their efforts. But the relational capital built up will be lost.

Some procurement regimes allow more elegant solutions to this problem. In the EU, the treaty principles of 2014 allow member states to use a range of restricted and negotiated procedures in cases where there is a limited pre-existing provider market – because the service required is very niche or very innovative, for example. While it is often supposed that the rules require open competition every time, they actually acknowledge that this is not always the best route to public value. As Frank Villeneuve-Smith and Julian Blake describe in The art of the possible in public procurement (2016), social, health and education services are subject to the ‘Light Touch Regime’ which allows public authorities a great deal of freedom as long as the process adheres to the treaty principles of proportionality (the process should be proportionate to the value of services) and fair and equal treatment (even restricted processes should be run in the open, so any willing provider can come forward if they want to). Beyond this, specific processes can be used to enable pre-tender and pre-award engagement, such as Competitive Dialogue, Prior Information Notices (PINs), Voluntary Ex-Ante Transparency (VEAT) notices, and Innovation Partnerships.

Beyond the specific procedure used, the tender process itself can be used to assess relational potential. Potential providers can be asked to propose particular ways of working, governance and decision-making processes, and shared principles that will underpin the delivery of the contract should they win. They can also be asked to propose risk-sharing and payment mechanisms, and goals for the end-outcomes, that will unlock flexibility during delivery without undermining the accountability and protections that the contract will offer the purchaser.

A risk-sharing mechanism that allocates risks to the party best placed to manage them

Contracts are not just about obtaining a service in return for money. They also provide a risk framework. Both what they include and what they leave out leads to certain risks falling on one party or another.

Some risks can be anticipated, and how they are shared can be decided up-front. For example, will a provider be compensated by a purchaser for an increase in input costs during delivery (e.g. staff wages), or will they be expected to absorb these? But other risks cannot be anticipated, so a relational contract might stipulate a governance mechanism or the creation of a forum for risks to be discussed on an ongoing basis. This will state the sort of decisions that need to be escalated for discussion, and who will be involved (see below).

Financial and delivery risks can also be managed through a contract’s payment mechanism. An up-front payment for services that are described in only the vaguest terms, as would be the case in a typical grant, keeps most of the risk on the purchaser / funder. They have already expended (or committed) the cost of the service, while having minimal control over what is provided and almost no recourse if something goes wrong. This is a perfectly legitimate approach in many circumstances, especially when the total contract amount is relatively low and the perceived goal alignment between purchaser and provider is already high – as you might expect between a charitable foundation and a community organisation, for example.

But for higher-value amounts or higher-stakes services where a misstep might have serious financial, reputational or human consequences, the purchaser may wish to transfer some risk onto the provider, so that they have a greater incentive to manage the risks that are within their control. The most extreme form of this is payment-by-results, whereby the purchaser pays the provider in arrears, and only when presented with externally verified evidence that pre-defined results have been achieved. In social services, these results could be more hip operations conducted, or more children educated. Payment-by-results puts most of the financial and delivery risk onto the provider – they must invest in a service and will only be compensated if that service is successful in achieving the outcomes the purchaser wants. Evidence from employment support programmes in many countries (Carter and Whitworth 2015) suggests that such extreme risk transfer can undermine relational practice, as it leads to opportunistic behaviour when providers interpret the rules of the contract in a way that minimises their chance of incurring losses. For example, when paid for each person who starts a job, providers would choose to work with individuals who they think are already close to employment, rather than those who most need support. Some recycled the same individuals through a service multiple times.

If grants and payment-by-results represent the two extremes in how financial risk is allocated between purchaser and provider, a pre-specified service contract – perhaps the most common form of public contract – represents the middle ground. The purchaser says what they want and the provider provides it, regardless of whether it fits the needs well or not. Such an approach may not be very suitable for conditions of complexity, changeable environment, goal alignment or mutual reliance, where the benefits of relational practice can be most keenly felt.

A payment mechanism can support relational practice when it helps to align the purchaser and provider around a set of verifiable goals; when it ensures financial and delivery risks are balanced according to which party is best placed to manage them; and when it works in support of the natural incentives towards trust-building outlined at the very start of this guide. That could mean devising a sophisticated payment mechanism that adopts various different features – a mix of up-front and result-based payments, with a mix of specific requirements alongside a mechanism for ongoing negotiation.

A decision-making structure that provides clarity on how ongoing adaptations will be agreed between the parties

Relational contracting anticipates – even welcomes – changes to the terms of engagement between the parties during the course of delivery. A relational approach is a way of dealing with uncertainty, whether internally or externally generated, and /or of making the most of goal alignment and a desire to collaborate closely. To unlock the benefits, ongoing open communication between the parties is essential. Problems need to be flagged early, and solutions jointly devised. Automatic consent of the other party for a proposed change should not be assumed – negotiation and compromise should be expected, and may take a long time. As well as negotiating with each other, each party will likely need to negotiate within their own organisation across departmental silos – with finance, procurement and legal colleagues, for example.

All of this points to the importance of agreeing processes for communication, negotiation and decision-making upfront. Such processes could be grouped under the heading of ‘governance’. Regular operational meetings between the parties should be scheduled, with their attendees stipulated. Guidelines should be agreed on what sort of decisions need to be escalated or approved by other stakeholders, and who they are escalated to. For example, a change to cashflow profile to deal with delivery delays could be dealt with operationally if flagged early; a change to the payment terms themselves is likely to require more negotiation and the involvement of a broader set of people on both sides.

While relational contracting can seem fairly abstract, there are very concrete examples of relational contracting practice out there – even though they may not be labelled or widely recognised as such. Mark Roddan, GO Lab Fellow of Practice 2020 and 2021, is the Joint Head of Procurement for North Somerset and South Gloucestershire Councils, two UK municipalities. He shared an example of a principle-based relational contract that South Gloucestershire entered into for consultancy services as part of a procurement savings programme. This demonstrates the potential for public sector commissioners and private sector service providers to enter into a mutually beneficial relational contract.

In Phase 1 of a programme to unlock savings from South Gloucestershire’s procurement budget, a number of opportunities for procurement savings were to be identified by a provider, and in Phase 2, the provider was invited to help deliver these opportunities. The inherent uncertainty of Phase 2 suggested a relational approach might be effective, and in the procurement process, the council asked providers to suggest how this uncertainty might be managed, as follows:

Phase 2 will be based on business partnering support to achieve the potential benefits that are identified as part of Phase 1. It is not realistic to try and define Phase 2 requirements and costs until Phase 1 is completed, therefore Phase 2 packages of work will be agreed with the Contractor based on the Schedule of Rates, discount structure and Payment by Results models set out in the Contractor’s tender response.

There is clearly a challenge to the Council under this approach with controlling costs and validating savings arising from the work undertaken by the Contractor. The Contractor will therefore be required to provide robust ongoing cost management and estimating mechanisms, and to work with the Council to demonstrate value from the packages of work that are undertaken. The Contractor is required to set out how this can be achieved as part of their tender.

South Gloucestershire Council (SGC) contracted Ernst & Young LLP (EY, a professional services firm) to deliver the contract. The precise nature of the services to be provided in Phase 2 was undefined, and might vary depending on how each opportunity progressed. This was acknowledged in the initial statement of work for Phase 2:

It is envisaged that the scope is likely to change as individual projects/initiatives are added/deleted/amended from the programme scope. Therefore, the scope section of this document is likely to be changed throughout the life of the programme.

As a result, instead of listing specific opportunities which would be pursued by EY and paid for by the council, a set of overarching commercial principles and governance arrangements were laid out in the document. The written contract set out the aims of the service, the need for flexibility, and forums for communication and governance. The default payment mechanism would be a contingent fee model, where payment is contingent on the delivery of project benefits. Where appropriate for particular projects, a fixed fee or working capital approach may be used (in the latter case, payment remains contingent on outcomes during implementation but part or all of payment is made ahead of implementation to be used as working capital).

A number of layers of governance would help to manage this approach in practice. A bi-weekly meeting between EY Programme leadership and the South Gloucestershire Head of Strategic Procurement would provide a progress update on ongoing projects, any projects being scoped and potential new opportunities. Any issues requiring escalation would be dealt with by the ‘Programme Board’, chaired by the SGC Director of Corporate Resources and comprised of representatives from EY and relevant council departments.

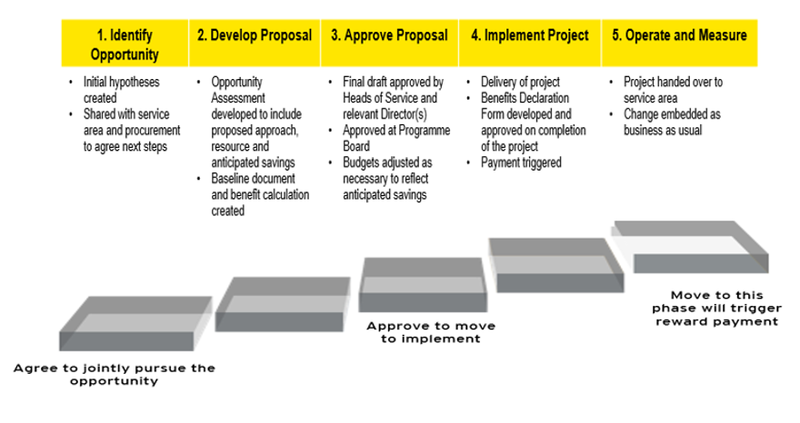

These governance structures would oversee a five-step process (see figure 1) for each particular project:

Figure 1: Project governance process - courtesy of South Gloucestershire Council

This example demonstrates the potential for a public sector commissioner and private provider to work more flexibly and collaboratively to deliver on the overarching aims of the contract, in the absence of the ability to specify upfront precisely what the service will entail.

Acknowledgements

1 minute read

This guide is based on Partnerships with principles: putting relationships at the heart of public contracts for better social outcomes by Nigel Ball and Michael Gibson.

References and further reading

1 minute read

Carter, E., Domingos, F., Rosenbach, F. and van Lier, F-A. (forthcoming). Contracting ‘person-centred’ working by results: frontline experiences from the introduction of an outcomes contract in housing-related support.

MacNeil, I. R. (1974). The Many Futures of Contracts. Southern California Law Review 47(3): 691-816.

Sloan, L. (2018). Market design in complex social services. Warwick Business School (Available on request).

Villeneuve-Smith, F. and Blake, J. (2016). The art of the possible in public procurement. E3M.

Vested Outsourcing (2022). About the Vested Faculty. Last accessed 22 August 2022.