Using impact bonds to improve education quality in low- and middle-income countries

Posted:

11 Jul 2022, 10:05 a.m.

Author:

-

James Ronicle

Director, Ecorys

James Ronicle

Director, Ecorys

Topics:

Impact bondsPolicy areas:

EducationTypes:

Global Systematic Review

In this blog, James Ronicle shares insights from a report on education impact bonds in LMICs produced by Ecorys, GO Lab and DeliverEd for the World Bank. The report builds on Ecorys and GO Lab's systematic review of outcomes-based contracts.

In this blog, James Ronicle shares insights from a report on education impact bonds in LMICs produced by Ecorys, GO Lab and DeliverEd for the World Bank. The report builds on Ecorys and GO Lab's systematic review of outcomes-based contracts.

When it comes to contracting the delivery of a public service such as education, governments traditionally pay up-front (that is, through a grant), or after services are delivered (that is, through a fee-for-service contract). One issue with this is that governments pay the same regardless of what education providers actually achieve. Underperforming schools with poor attainment results have little financial incentive to improve if they simply receive a grant at the start of every school year.

Outcomes-based contracting (OBC) is used by governments to contract public services in a way that creates financial incentives for good performance. In OBC, governments pay providers only when they achieve specified outcomes. Although OBC is attractive to policymakers because it shifts the responsibility for achieving outcomes to the organisations that actually deliver the services, it is also risky. Providers run the risk of losing money if they don’t achieve outcomes because they must cover the up-front costs themselves.

Impact bonds are a type of outcomes-based contract that addresses this issue by involving a third-party: an investor. The investor provides the up-front capital and in doing so takes on the risk of underperformance. They do this because they can make a profit if service providers overperform (that is, they achieve more outcomes and are paid more than expected). International development agencies and financial institutions now consider impact bonds when they contract development interventions in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). However, we don’t yet know exactly in what circumstances they work best, how they should be designed, and what effects they have compared to other ways of contracting development interventions.

The state of play

Most of the time, impact bonds are used by governments in high-income countries, but some impact bonds have been launched by governments in low- and middle-income countries or by international donors such as the World Bank. Education impact bonds typically aim to improve children’s learning and attainment, increase school enrolment rates or develop teaching capacity in target communities.

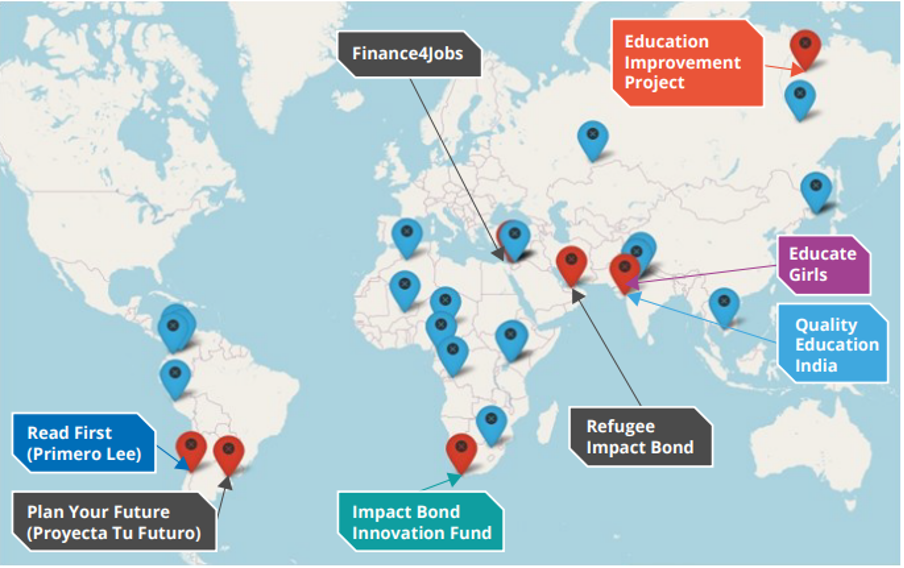

So far, five such projects have been launched in LMICs, funded by philanthropic organisations that want to improve education quality in developing countries. The map below shows where these five projects were launched, plus another three impact bond projects (in grey) which had some education objectives but focused more on employment. Another two purely education-focused impact bonds will be launched in Ghana and Sierra Leone later in 2022.

Ecorys were commissioned by the World Bank’s Results in Education for All Children (REACH) trust fund to investigate further. We teamed up with the Government Outcomes Lab and Deliver Education Reforms Project (both based out of the University of Oxford’s Blavatnik School of Government) to review the available evidence comprehensively and systematically, drawing on a broader study we have been conducting with the GO Lab since 2021. The systematic review of outcomes-based contracts aims to review the evidence on outcomes-based contracts in all sectors, and this report specifically focused on the evidence related to the education impact bonds launched in LMICs.

Set up and launch

The final report details the process of setting up and launching education impact bonds (including the key challenges, sticking points and factors leading to success). It describes how, although the ideal conditions for launching impact bonds are rarely present in LMICs, they could be developed by securing buy-in from local stakeholders, building the capacity of providers to be involved in impact bonds and collecting high-quality data prior to launch.

It concludes that international development agencies and financial institutions could play a key role in laying this groundwork because of their technical knowledge, convening power and established links to partner governments. Moreover, the report highlights the value of generating more accessible knowledge on ‘best practice’ approaches to the difficult choices that must be made in order to launch impact bonds, such as cohort definition, outcome selection, attribution and pricing, and contracting.

The impact bond effect?

Although we found useful evidence regarding the process of developing and launching education impact bonds, we found hardly any empirical research comparing the effects of education impact bonds to other ways of contracting the same services. The report contains a summary of the qualitative evidence on the effects of impact bonds, which suggests that the unique combination of outcomes funding, shared financial risk and inclusion of new partners (e.g. investors, intermediaries) can lead to service providers focusing more on delivering what is needed to achieve outcomes, as well as stronger adaptive management and greater collaboration between project stakeholders.

However, we can’t be sure yet whether this leads to more outcomes. To strengthen the evidence base, the report concludes that international development agencies and financial institutions interested in using impact bonds should fund more experimental programmes involving impact bond and similar non-impact bond projects in LMICs.