Meaningful metrics - what can we learn from health economics in evaluating social policies?

Posted:

22 Aug 2019, 10:49 a.m.

Author:

-

Mehdi Shiva

Economist

Mehdi Shiva

Economist

Topics:

MeasurementPolicy areas:

Health and wellbeingThe history of social science measurement dates back a long way. It emerged in the early 19th century with the work of Pierre Guillaume Frédéric Le Play (1806-1882). He is credited with establishing what has become the modern-day social survey. It has developed a lot from there and now we see more complex models. This blog, written by Mehdi Shiva an Economist at the GO Lab, will briefly review the current state of measurement in social sciences, point out some of the shortcomings, and urges further conversation around social metrics.

What is the issue?

Standardised social impact metrics are overwhelmingly focused on outputs and activities of an intervention rather than measuring for outcomes. For example, improved ‘attendance rate’ of students is not a sufficient condition for better education. This poses a few problems, namely, that it is not measuring anywhere close to the impact of the intervention. Strictly collecting data on outputs and activities can lead those reporting to feel like they are being called to meet quotas rather than facilitate their social mission.

There is increasing demand to shift the focus from interventions achieving outputs, to achieving ‘outcomes’ and ‘impact’. This is how impact bonds and impact investment came into being. They are both focused on impact measurement, with the aim of understanding both financial and social return on these investments. This shift is important as what we measure shapes how we design, develop and deliver an intervention. For example, if you are asked to report on number of schools opened rather than improved Maths scores , you may prioritise the quantity of schools over the quality of experience. Contrarily, if you report on Maths scores you are more likely to focus on educational improvement.

In social science disciplines, the lack of scientific theories is often reflected in the lack of well-accepted common metrics (also known as targets or measures). With scientific theory, measurements can often be used to confirm, reject, or refine hypotheses. Moreover, standardised measures need to be accepted by other institutions to be useful. Well-structured standardised metrics could help us with make better decisions around resource allocation, pricing, assessing value for money, and impact measurement.

How has economics contributed to health studies?

Economics has developed a powerful method for using market data prices and quantities to create standardised measures of income and other related variables that can be compared across people, countries, and time. The economic framework, however, fails to account well for goods and services that are produced and consumed outside markets. One approach to deal with this is to develop new measures of choice sets and behaviours in order to estimate prices. Another is to relax the economist’s preference for objective data and revealed preference in favour of subjective measures.

For example, health-related quality of life is measured through using the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) at the National Institutes of Health (NIH). People began measuring morbidity along with mortality. The former includes how people feel, how health problems affect them, their disabilities, and the latter measures whether someone is alive or dead. This lead to the development of Quality Adjusted Life Years (QALY). This measure combines Health Related Quality of Life (HRQoL) and mortality into a single number and allow for comparison across health conditions. This is in line with the growing eagerness of economists to consider supplementing their market-based measures with subjective ones (e.g. SC-QALY by Netten et al., 2012).

What is already out there?

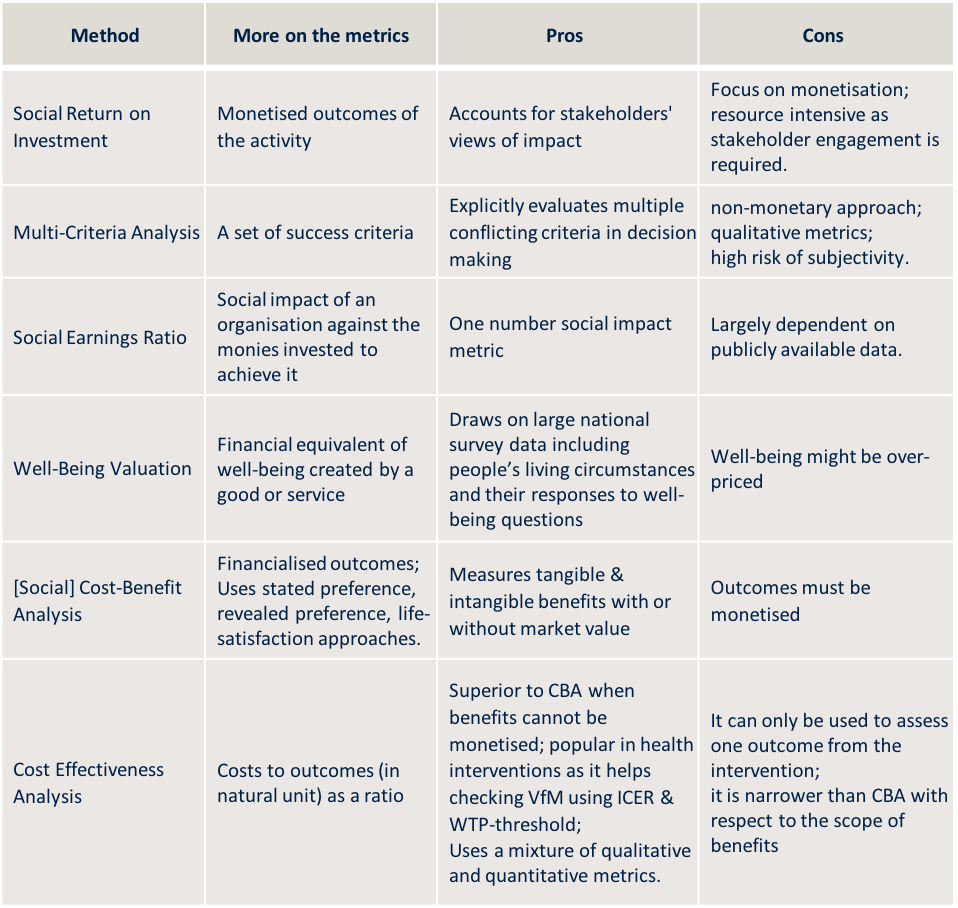

There are a number of different models for measuring social impact, each of them using a different set of metrics and approaches for their analysis. We cannot single one out as the dominant model as preferences change across fields and situations. For instance, Cost Effectiveness Analysis (CEA) might be better than Cost Benefit Analysis (CBA) when comparing interventions that you cannot monetise. However, CBA may be better when making decisions between programmes with either the same or different outcomes.

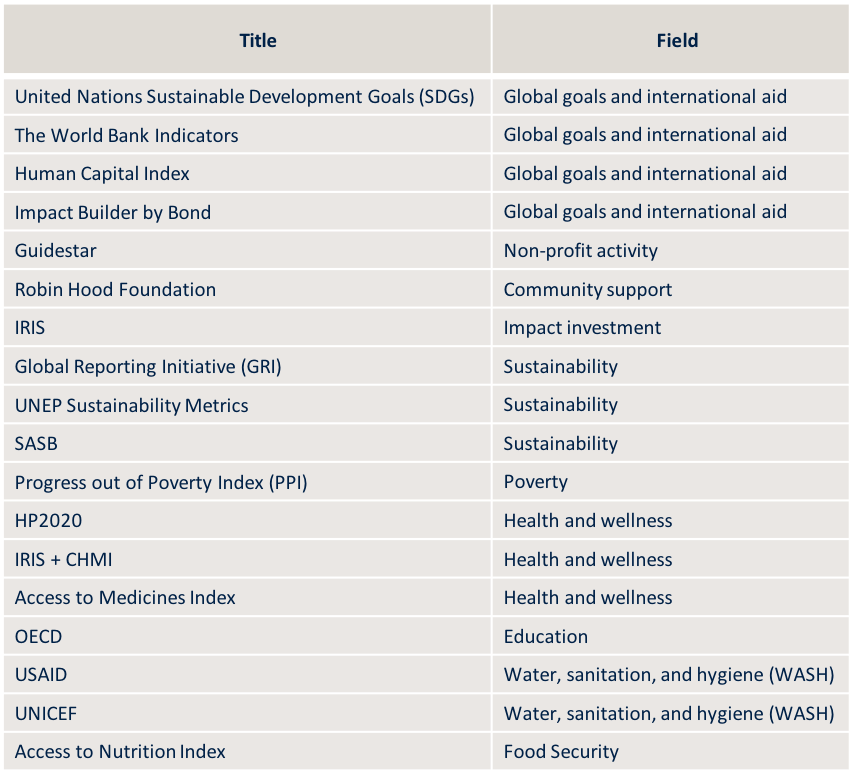

Below is a table outlining the key models of social impact measurement. It also outlines the advantages and disadvantages. Table 2 lists common metrics used when evaluating different fields.

One measure to rule them all

In the social, behavioural, and economic sciences, standardisation of measures can help build evidence as it allows valid comparisons across time, place, or units of observations (e.g., persons, families, settings, localities, organisations). It also can create common understandings, when measurement intersects with policy. However, standardisation can also allow us to lose information, and if we standardise too much this can give us extensive evidence that is uninformative and misleading. A delicate balance must be negotiated between standardisation of measurement and validity of social scientific community.

One size does not fit all!It is not always ideal to have one common metric, but rather a few metrics widely used - different metrics serve different purposes. When there is no suitable measure for wide spread use, multiple measures can be used to help test robustness. So, maybe a harmonisation of measures is a good alternative when standardisation is not appropriate. For instance, consensus around a specific blend of education metrics such as student’s grades, attendance, and behaviour could represent ‘quality of education’ better than any of them individually. Scientists tend to favour harmonisation because agreement can be reached through trial and error of different ideas. Harmonisation is seen as a form of standardisation established among scientists, not imposed on them (National Research Council, 2011).

Would you like to learn more about this from a set of distinguished experts? Please join us in our conference session Measuring What Matters on 6th September at Blavatnik School of Government.