Plan for Jobs and employment support: Government Outcomes Lab response to the call for evidence

Posted:

10 Oct 2022, 1:50 p.m.

Authors:

-

Eleanor Carter

Academic Co-Director, Government Outcomes Lab

Eleanor Carter

Academic Co-Director, Government Outcomes Lab

-

Michael Gibson

Research and Policy Associate, Government Outcomes Lab

Michael Gibson

Research and Policy Associate, Government Outcomes Lab

-

Emily Hulse

Research Associate, Government Outcomes Lab

Emily Hulse

Research Associate, Government Outcomes Lab

-

Adam Whitworth

Professor of Employment Policy, University of Strathclyde

Adam Whitworth

Professor of Employment Policy, University of Strathclyde

Policy areas:

Employment and trainingRegions:

UK

Last month, the UK Parliament's Work and Pensions Select Committee held a call for evidence as part of their inquiry into the effectiveness of Government support to get people into employment, including disadvantaged groups such as those in low-paid jobs and young people. In collaboration with Professor Adam Whitworth (University of Strathclyde), and drawing on both GO Lab and wider research into employment support, we submitted the below response, focusing on how the government can best support those who face the greatest barriers to labour market inclusion.

Last month, the UK Parliament's Work and Pensions Select Committee held a call for evidence as part of their inquiry into the effectiveness of Government support to get people into employment, including disadvantaged groups such as those in low-paid jobs and young people. In collaboration with Professor Adam Whitworth (University of Strathclyde), and drawing on both GO Lab and wider research into employment support, we submitted the below response, focusing on how the government can best support those who face the greatest barriers to labour market inclusion.

The Government Outcomes Lab (GO Lab) is a research and policy centre based in the Blavatnik School of Government, University of Oxford, which investigates how governments partner with the private and social sectors to improve social outcomes. This submission was compiled Dr Eleanor Carter (Research Director), Michael Gibson (Research and Policy Associate) and Emily Hulse (Research Associate). This is a joint submission with Professor Adam Whitworth, Professor of Employment Policy in the Scottish Centre for Employment Research, Strathclyde Business School, University of Strathclyde. He has published widely on various aspects around the effective design of employment support interventions and has supported UK employment policy design across central, regional and local government.

Context

Employment support services have been a key area of experimentation in public service delivery through different forms of contracting and partnership arrangement. The use of alternative commissioning approaches by the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) provides a substantial but complex body of evidence relating to the appropriate partnership and accountability structures for high-quality services. As an applied research group, the Government Outcomes Lab has brought together rigorous academic research with on-the-ground insights from policy and practice in order to investigate the use of innovative partnership structures for public services which seek to address complex social problems.

What isn’t working? – The challenge of commissioning employment support services for those furthest from the labour market

Historically, DWP has commissioned private sector providers using very large scale and (at times) internationally ‘extreme’ forms of Payment-by-Results (PbR) (Carter, 2018). Schemes such as the Work Programme are understood to perform well on the ‘efficiency’ aspect of value-for-money as outcome fees were lean and initial under-performance served to push down unit costs further. The flip side of this ‘cheapness’ is under-investment – for example, it is estimated that DWP invested roughly half of intended to support disabled people (Riley et al., 2014). In the context of (overly) ambitious performance targets and costs pressures, providers’ sought cost-efficiencies and profit maximisation through a low-cost, standardised service that was poorly tailored to individual needs and minimally helpful to most (Carter & Whitworth, 2015; Rees et al., 2014). There are concerns that mainstream ‘welfare to work’ programmes may have pushed vulnerable participants facing the greatest barriers to employment, such as mental health conditions and disabilities, further from paid employment rather than towards workplace inclusion (Scholz & Ingold, 2020).

The group of people who are economically inactive are not a single homogenous group and recognising the different courses and motivations for economic inactivity is important both to target the policy response effectively as well as to design that policy response effectively.

The situation for economically inactive individuals with health conditions and disabilities is often very different to, for example, the reasons that older workers have left the labour market following COVID-19. Whilst heterogeneity again exists, for these individuals it is our view that the DWP policy response has been inadequate. Individuals in receipt of Employment Support Allowance (ESA) and its Universal Credit equivalent receive little to no offer of employment support, especially in the (by volume large) Support Group but even within the WRAG group. This is despite most individuals with disabilities saying that they would like to work if the right employment support and right job were available. The current employment support system thus wastes significant talent and frustrates people’s work ambitions by failing to provide meaningful employment support for this group. In terms of its form, evidence suggests that employment support interventions for such individuals needs to be voluntary, adequately resourced and intensive, and person-centred. This would offer the prospect of meaningfully improving their quality of life. The voluntary nature of such support is also important in order to achieve the buy-in and support of health professionals and other local partners. Since they are the ones who will be working with supporting such individuals and who the DWP may well need to rely on to advertise programmes, make referrals or offer integrated support within the employment programme.

With all of this in mind, we have identified three overarching challenges when it comes to ‘what isn’t working’ for those furthest from the labour market:

1. Lack of person-centredness, particularly for those who are often understood as being further from the labour market

Large-scale mainstream contracted provision has not appropriately connected with or supported participants who are understood to experience more complex and/or compound barriers to the labour market. Commentators indicate limitations with status quo provision in UK support programmes that tend to focus on entering into the labour market and less on remaining in work (Gardiner & Gaffney, 2016). There is also a need for programmes to account for the needs and aspirations of people with existing mental health problems and tailor support to individual circumstances (Wilson and Finch, 2021). In order to adequately support this cohort, services must be more personalised. However, unlocking genuine person-centredness may require both higher unit costs and alternative partnership arrangements between the commissioning department and delivery networks.

2. Lack of adaptability in the face of a changing labour market

Long-term and large-scale Prime contracts for employment support schemes are known to have struggled when labour market conditions change during implementation. For example, while the Flexible New Deal was designed to link payment to outcomes, there was no evidence of employment impact associated with the programme (Vegeris et al. 2011), and it was ultimately renegotiated to pay providers regardless of outcome achievement. Fluctuations in supply of and demand for labour have been exacerbated by COVID-19. Employment support programmes must acknowledge the need for adaptation and responsiveness to a changing labour market, allowing them to continue to prioritise outcomes achievement, particularly in the context of a fluctuating situation surrounding inactivity and the potential for a recession.

3. Insufficient sharing of research and data to support learning community

There is an active and engaged community of practitioners and academics who reflect on best practice within the commissioning of employment support, from across the private and social sectors, academia, and within DWP and local government. This wider research and practice community have valuable insights that could help to maximise the effectiveness of the Department’s employment support programmes. However, their ability to offer reflections is severely limited by the lack of publicly available research and performance data released by the Department in recent years. For example, to the best our knowledge, there has been no performance data released to date on the Restart programme.

How could these challenges be addressed?

The international evidence base around employment support is large and varied. In short, there is no magic bullet from the international experience that we can provide to simply ‘lift and shift’. However, what the international evidence does suggest is a series of conditions and contexts that can help or hinder employment support programmes. If we reflect on the UK employment support system on that basis, we can identify the strengths and weaknesses in the UK approach to think about how we might drive improvements.

In summary, in terms of strengths DWP have developed extensive expertise around:

- programme design and commissioning;

- an excellent analytical community;

- excellent data and process around management information and outcomes validation that enable effective performance management and payment; growing use of valuable HMRC earnings data;

- a vibrant private, third sector and local authority community of employment support providers.

In terms of weaknesses, DWP are:

- highly centralised, meaning localities do not often have sufficient opportunity to work collaboratively with DWP strategically and Jobcentres operationally in order to build the types of locally integrated programmes that maximise effectiveness and pooled resourcing;

- contracted provision has in recent years been far too naïve in terms of the faith that it has placed on aggressively marketized contracted programmes’ ability innovate and to deliver effectively and equitably;

- the UK’s austere conditionality and sanctions regime is not aligned to evidence or common international practise. This does more harm than good in terms of DWP achieving its own objectives around supporting people to move into work and clearly does more harm than good for benefit claimants themselves;

- connections between the employment and health systems centrally and locally have improved since the creation of the joint Work and Health Unit but remain too disconnected in ways that undercut the DWP’s ambitions to seriously transform health related unemployment;

- whilst we empathise with the high level of desire to support in-work progression, we have serious misgivings about its measurement around narrow earnings progression, the application of conditionality to those already in employment, and the reality of stretched and weakly resourced Work Coaches to support it on the ground.

It is welcome that DWP have moved away from the aggressively cost-discounted and extreme PbR Work Programme type model which multiple of our and others research has evidenced carried significant risks, perverse incentives and undesirable outcomes both for claimants and for the DWP themselves in terms of meeting their own stated programme objectives (Whitworth and Carter 2017; Carter and Whitworth 2016). It is notable that the DNA of this type of contracted programme still exists within Work Programme’s successors (e.g. Work and Health Programme, Restart), even if a somewhat diluted form. This is something that we urge the Committee to continue to be aware of and we caution any re-hardening of that approach given its evidenced problems.

Within Jobcentre Plus and direct services

As we have published in recent academic work (Whitworth 2018), we believe that there are major weaknesses in the Jobcentre employment support offer. However, there are also significant opportunities for meaningful positive reform that helps DWP to better utilise its resources and achieve its objectives whilst simultaneously better helping unemployed and economically inactive individuals to achieve their employment aspirations.

Our academic research highlights three core problems in the Jobcentre employment support regime. We refer to these as the three Cs:

- Capacity: caseloads are far too high to enable meaningful employment support to all;

- Connectivity: Work Coaches and Jobcentre are too isolated from important wider services and budgets locally (e.g. health, housing, debt, etc.) that are needed to support many of their benefit claimants within the employment support;

- Conditionality: the Jobcentre is premised on an internationally aggressive conditionality and sanctions regime that does not map onto evidence and that undercuts rather than supports its effectiveness.

In terms of capacity, there are simply not enough Work Coaches for the numbers of benefit claimants that need support, in order for that support to be meaningful. Caseloads are far too high to enable meaningful employment support to all. The result is acute rationing of employment support from Work Coaches to claimants. As a result, Work Coach support is effective for far too small a percentage of the total unemployed and inactive caseload.

In terms of connectivity, Work Coaches locally are too isolated from the various wider local services, partners and budgets (e.g. health, housing, substance misuse, debt, etc.) that are also needed to support many of their caseload. This means both that those benefit claimants fail to receive the type of integrated support offer which they require, but also that Jobcentre cannot in effect supplement serious limits to their own budgets by leveraging in resource from other local partners who address shared population groups and overlapping problems. This is particularly acute given current resource constraints, and it is imperative that DWP strategically and Jobcentre operationally work proactively and collaboratively with local partners to build locally integrated employment support partnerships that maximise and coordinate all of the budgets and services that are available. It is only by doing so that we can together maximise both the effectiveness and value for money of the collective spend and that Jobcentre and various local partners can better support these shared client/individuals/patients and their multiple overlapping support needs.

The Jobcentre conditionality and sanctions regime is aggressive compared to international perspective and the evidence is clear around its limited (indeed negative long term) employment effects. Including its significant economic as well as physical and mental health harms to benefit claimants, in particular those who are already most vulnerable and disadvantaged.

Within partnerships with independent providers

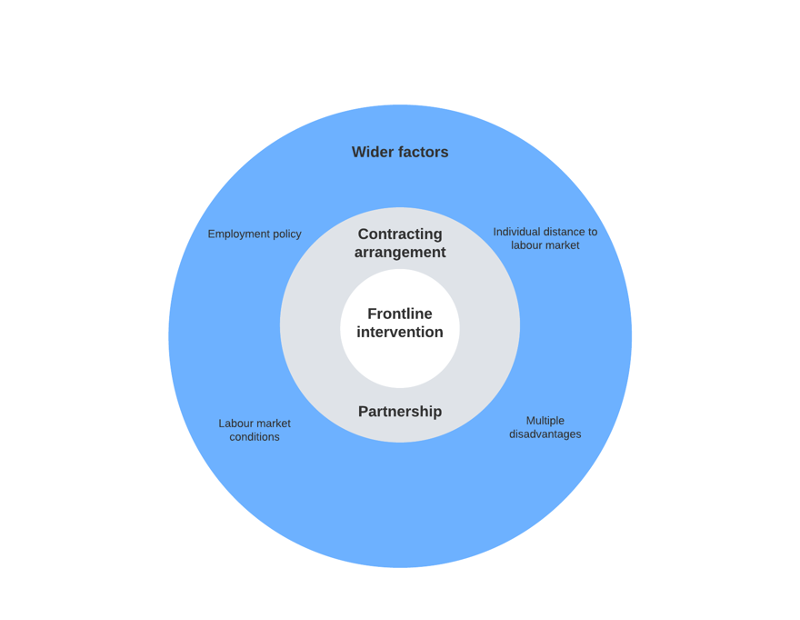

Evidence from both our own research and wider literature on employment support for vulnerable populations suggests that effective support might lie at the intersection between productive partnerships and contracting arrangements, and good quality frontline interventions. A good-quality intervention may not be effective in a particular context if the contracting arrangement is overly transactional or creates perverse incentives, while the most effective collaboration in the world cannot achieve impact if the intervention it delivers is not itself effective.

What does a good quality intervention look like?

At the heart of successful employment programmes are well-designed interventions that meet the needs of the cohort of users they serve. A ‘good quality intervention’ may not be a single piece of support, but rather a package of support that is tailored to an individual’s support needs. This will likely include ‘direct’ employment support including personalised advice and skills training, but may also extend to health, housing, and financial advice (Whitworth and Carter 2017). The overarching programme may specify a particular set of frontline intervention(s), or adopt a ‘black box’ approach, leaving the choice of appropriate support to the service provider. A strong evidence base of prior success may provide a strong foundation for the selection of appropriate interventions (either by the Department in programme design or by providers in a black box approach), although such interventions may still require tailoring to meet the specific context and needs of a particular cohort (Cartwright and Hardie 2012).

Contracting for collaboration

In addition to the quality of the frontline intervention, the way in which that intervention is delivered can also affect how successful it is. As noted above, many DWP programmes have relied on some form of PbR. Our research on the use of outcomes-based contracting, more broadly and specifically in employment support, suggests that well-designed outcomes-based contracts might offer a range of benefits, including improving collaboration and facilitating innovation (Carter et al. 2018). However, it also indicates the need for careful design and definition of ‘outcomes’ in order to ensure the interests of both purchaser and provider are adequately aligned. GO Lab research suggests that a robust outcomes framework requires tight definition of the eligible cohort, careful alignment of outcomes to policy intent, and accurate pricing of those outcomes (FitzGerald et al. 2019). Evidence from research on the Work Programme further emphasises the importance of cohort and outcome definition, including better segmentation of groups based on their distance from/barriers to the labour market and/or a focus on group rather than individualised outcomes (Carter and Whitworth 2015).

More broadly, contracting partnerships may be enhanced by adopting a more relational approach. Evidence suggests that traditional transactional contracts may be inappropriate for more complex services (Brown et al. 2018), and instead relational contracting, emphasising collaboration and flexibility through trust, may be more appropriate to address both internal and external uncertainty (Ball and Gibson 2022). Employment programmes, particularly those serving vulnerable groups, face both the challenges of adequately addressing multiple and often reinforcing barriers to employment for their service users (the right-hand side of Figure 1, above), and wider labour market conditions and employment policy (left-hand side). Relational contracting frames these as challenges to be overcome collaboratively by the purchaser and provider in order to achieve the overarching aims of the contract – supporting service users into good jobs – rather than assuming each party will attempt to maximise its own self-interest (Van Slyke 2007).

Case study – MHEP

The Mental Health and Employment Partnership (MHEP) programme offers an example of how an evidence-based intervention can be combined with a collaborative partnership structure. The following draws on insights from the GO Lab’s evaluation of MHEP projects co-commissioned under the Life Chances Fund (Hulse et al. forthcoming). In MHEP, each outcomes contract is led by a local authority/clinical commissioning group and payment is made contingent on the achievement of pre-specified, measurable outcomes: engagement of users, job entry, and job sustainment. This allows the delivery of an intervention known as the ‘Individual Placement and Support’ model (IPS). IPS is based on ‘place then train’ principles and there is evidence suggesting that it is more effective in traditional approaches such as vocational training and sheltered work (de Graaf-Zijl et al., 2020). Service providers, local commissioners, and the MHEP team have all suggested the interaction between the IPS intervention and the surrounding outcome contracting arrangement has been generally fruitful – although not without challenges.

We have found that the outcome contract allowed a clear focus on performance parameters which helped retain consistency and stability. Given limited capacity in commissioning units, providers were able to access more support than they would without MHEP involvement, in three main categories: operational, analytical, and convening & advocacy.

MHEP's analytic inputs involved performance monitoring, enhanced data access and benchmarking. Some interviewees found great value in the data analysis and intelligence MHEP provided, which was seen as over and above what stakeholders could normally access in traditional commissioning. Although projects were used to working towards similar outcome measures, MHEP’s performance management function was seen to drive additional focus on achieving outcomes. The operational support in the MHEP project took the form of IPS specialists, solution-orientated support and commissioning/contracting guidance, while convening and advocacy inputs included MHEP sign-posting to funding opportunities, leading Life Chance Fund application and advocating for IPS and high-impact services. Providers spoke highly of the working culture within the partnership. Most importantly, MHEP’s role in identifying and successfully unlocking the Life Chances Fund funding was key in adding financial and human resources to projects, which was seen as hard to access otherwise.

On the other hand, some stakeholders were more cautious in describing MHEP's distinction over working with local authorities. While they acknowledged that MHEP’s assistance in applying for and unlocking Life Chances Fund funding had been key, they did not perceive its other functions to be markedly additional to existing practices. Providers sometimes found MHEP’s approach too theoretical and removed from the actual delivery of IPS. This was particularly the case where local knowledge from the local authority was seen as vital. In addition, it was perceived that the language used by MHEP was sometimes very different and caused confusion.

Overall, the MHEP example shows that in order to enable high quality IPS and IPS-like services to take hold may require a multi-faceted employment services offering, including 1) support to develop and implement outcome-based contracts at local level; 2) finance since it brings together third-party investment through a social impact bond and facilitates the pooling of government funding from central outcome top-up funds (Life Chances Fund) and local co-commissioners (local authorities and/or clinical commissioning groups); and 3) a robust high-quality intervention as it also facilitates access to IPS services, specialists and technical resources.

As academic researchers centred on evidence as to what works regards the effectiveness, cost efficiency and experiences of different employment support designs we commend the DWP’s policy activities around IPS and Supported Employment. We applaud DWP for the work that it has done both to follow and to grow the international evidence around IPS and Supported Employment and we recognise the degree of innovation as well as rigour that the DWP are showing in these interventions and their evolution.

Conclusion and recommendations

Many recent DWP employment programmes have been successful at achieving the economy criteria of value-for-money, but have perhaps done so at the expense of other elements – effectiveness, efficiency and equity. They have lacked appropriate support for those furthest from the labour market, have struggled to adapt to changing labour market conditions, and have failed to share data and learning.

However, promising insights from the theory and practice of employment support and broader public service contracting offer an alternative that might better serve a more holistic conception of value-for-money. These insights suggest that improved direct provision, as well as the combination of carefully designed but flexible partnership arrangement and high-quality, person-centred intervention, can better serve those most in need of support into employment.

In order to achieve this, the Department should:

- Address challenges within Jobcentre Plus around capacity, connectivity and conditionality

- Explore alternative, more relational partnership models that actively facilitate flexibility and adaptation, including co-commissioning with local actors

- Ensure the quality of a holistic package of interventions is considered, appropriate and personalised to the needs of individuals

- Improve data sharing to allow assessment and learning by the wider community

Ball, N. and Gibson, M. (2022). Partnerships with principles: putting relationships at the heart of public contracts for better social outcomes. Government Outcomes Lab, Blavatnik School of Government, University of Oxford.

Brown, T. L., Potoski, M. and Van Slyke, D. M. (2018). Complex Contracting: Management Challenges and Solutions. Public Administration Review 78(5): 739-747.

Carter, E. (2018). ‘Making markets in employment support: does the variety of quasi-market matter for people with disabilities and health conditions?’, in: Needham, C., Heins, E., Rees, J. (Eds.), Social Policy Review 30: Analysis and Debate in Social Policy. Policy Press, Bristol.

Carter, E., FitzGerald, C., Dixon, R., Economy, C., Hameed, T. and Airoldi, M. (2018). Building the tools for public services to secure better outcomes: Collaboration, Prevention, Innovation. Government Outcomes Lab, Blavatnik School of Government.

Carter, E. and Whitworth, A. (2016). Work Activation Regimes and Well-being of Unemployed People: Rhetoric, Risk and Reality of Quasi-Marketization in the UK Work Programme. Social Policy and Administration.

Carter, E. and Whitworth, A. (2015). Creaming and Parking in Quasi-Marketised Welfare-to-Work Schemes: Designed Out or Designed In to the UK Work Programme? Journal of Social Policy 44(2): 277-296.

Cartwright, N. and Hardie, J. (2012). Evidence-Based Policy: A Practical Guide to Doing It Better. Oxford University Press.

De Graaf-Zijl, M., Spijkerman, M., & Zwinkels, W. (2020). Long-Term Effects of Individual Placement and Support Services for Disability Benefits Recipients with Severe Mental Illnesses.

FitzGerald, C., Shiva, M., Carter, E. and Airoldi, M. (forthcoming). Procuring Value-for-Money: Reframing accountability, effectiveness and cost in the design of public service contracts.

FitzGerald, C., Carter, E., Dixon, R. and Airoldi, M. (2019). Walking the contractual tightrope: a transaction cost economics perspective on social impact bonds. Public Money & Management 39(7): 458-467.

Gardiner, L. and Gaffney, D. (2016). Retention deficit: a new approach to boosting employment for people with health problems and disabilities. Resolution Foundation.

Wilson, H. and Finch, D. (2021). Unemployment and mental health: Why both require action for our COVID-19 recovery. Health Foundation.

Hulse, E., Shiva, M., Hameed, T. and Carter, E. (forthcoming). Mental Health and Employment Partnership LCF Evaluation. Government Outcomes Lab, Blavatnik School of Government.

Rees, J. Whitworth, A. and Carter, E. (2014). Support for All in the UK Work Programme? Differential Payments, Same Old Problem. Social Policy & Administration, 48(2), 221-239.

Riley, T., Bivand, P. and Wilson, T. (2014). Making the Work Programme work for ESA Claimants: Analysis of minimum performance levels and payment models. Institute for Employment Studies.

Scholz, F. and Ingold, J. (2020). Activating the ‘ideal jobseeker’: Experiences of individuals with mental health conditions on the UK Work Programme. Human Relations 74(10).

Van Slyke, D. M. (2007). Agents or Stewards: Using Theory to Understand the Government-Nonprofit Social Service Contracting Relationship. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 17(2): 157-187.

Vegeris, S., Adams, L., Oldfield, K., Bertram, C., Davidson, R., Durante, L., Riley, C. and Vowden, K. (2011). Flexible New Deal evaluation: Customer survey and qualitative research findings. Department for Work and Pensions.

Whitworth, A. (2018). Transforming employment support for individuals with health conditions?: 3Cs to the aid of the Work, Health and Disability Green Paper. Journal of Poverty & Social Justice.

Whitworth, A. and Carter, E. (2017). Rescaling employment support accountability: From negative national neoliberalism to positively integrated city-region ecosystems. Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space, 36(2).