Whose data is it anyway?

Posted:

7 Mar 2023, 5 p.m.

Author:

-

Srinithya Nagarajan

Policy Engagement & Communications Associate, Government Outcomes Lab

Srinithya Nagarajan

Policy Engagement & Communications Associate, Government Outcomes Lab

Topics:

Outcomes-based approaches, Impact bonds, DataTypes:

Peer learning, INDIGO

There is a tremendous value in learning from data shared within organisations. Have you ever been in a situation where you had the opportunity to share ‘your’ data, but you were not sure whether it was okay to do it? When the ownership of data is unclear, we may not share data and others may follow suit. As a result, we end up in a lose-lose situation where we, and other peers, miss the learning opportunity. But does it need to be this way? In this blog, Srinithya Nagarajan shares the key insights from a recent INDIGO peer learning session on the topic of data ownership and access.

There is a tremendous value in learning from data shared within organisations. Have you ever been in a situation where you had the opportunity to share ‘your’ data, but you were not sure whether it was okay to do it? When the ownership of data is unclear, we may not share data and others may follow suit. As a result, we end up in a lose-lose situation where we, and other peers, miss the learning opportunity. But does it need to be this way? In this blog, Srinithya Nagarajan shares the key insights from a recent INDIGO peer learning session on the topic of data ownership and access.

This blog builds on contributions from Mara Airoldi, Ruairi Macdonald, Juliana Outes Velarde, Harry Bregazzi and the participants of the INDIGO peer learning session.

Data is essential to inform our decisions and learn from past experiences. Many practitioners consider data to be a public good and seek academic institutions to be an honest broker in providing the information while ensuring the required level of quality. However, there is disagreement among stakeholders on what types of data can be shared publicly. There are also ethical considerations and concerns over confidentiality and compromising commercial or privacy interests. Although there is an agreement on the importance of open data, there are genuine challenges.

In November 2022, the INDIGO network convened a diverse group of practitioners working with outcomes contracts to discuss data sharing practices. The goal of the session was to discuss which data can easily be shared and which data should be kept in confidence.

What data do we have, and what data do we want?

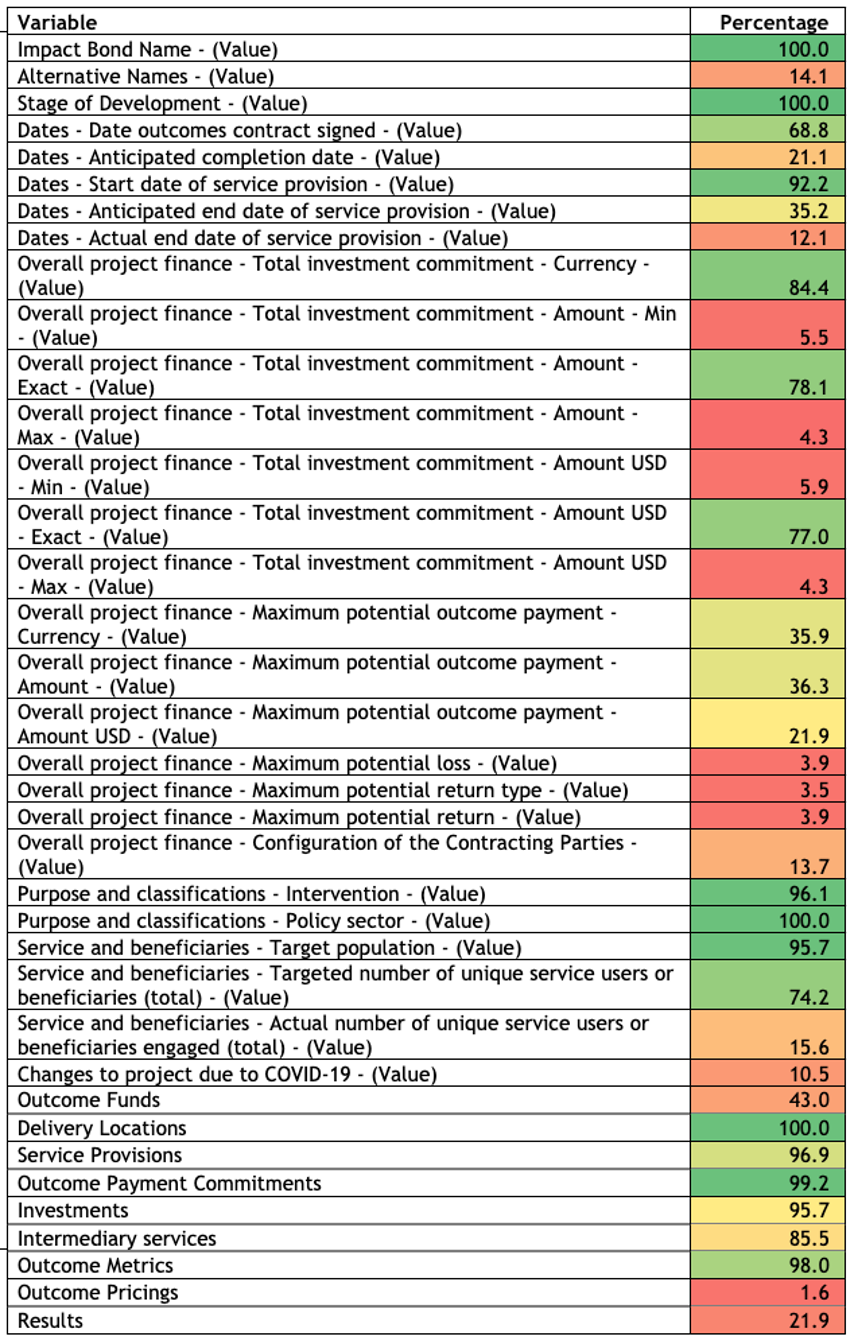

GO Lab Senior Data Steward Juliana Outes Velarde discussed data completeness of the Impact Bond Dataset, an open dataset that we co-produced with the community of organisations working on impact bond projects. The process of collating the dataset has proved a catalyst for thinking through, and discussing with stakeholders, a collective response to these challenges. The data completeness varies significantly from project to project. The following pictures show the percentages of data coverage that the Impact Bond Dataset has for every variable.

Table 1: Impact Bond Dataset Data Completeness Report as of 14 November 2022

There is significant variation in data completeness across different variables. Variables with good coverage include the impact bond name, stage of development and policy sector. Outcome pricing and results do not have good coverage. However, we need to exercise caution in interpreting the red variables. For instance, red variables such as alternative names and outcomes fund indicate that many projects do not have alternative names or an associated outcomes fund. These are not instances of low coverage, but simply the nature of impact bond projects.

Philip Messere, based at The National Lottery Community Fund, shared that useful data for an outcome funder is about service users, outcome metrics, progression through the pipeline to achieve outcomes, final outcomes achievements, outcome payments and cost breakdown. It would be helpful to have a clear understanding of how other parties are defining and measuring costs. If there is no clarity on this, there is a risk of cost breakdown inconsistency. GO Lab Fellow of Practice, Dr Nevilene Slingers, based at South African Medical Research Council, shared that as an intermediary, it was difficult to access outcome pricing data. Andrew Levitt, based at Bridges Outcome Partnership, explained that the data that fund managers find helpful is about outcomes achievements and the factors behind those achievements.

Barriers to data sharing, and how we might overcome them

GO Lab Fellow of Practice Daniella Jammes, based at Freshfields Bruckhaus Derringer, shared that data protection is key when considering sharing data. In most circumstances, it would not be an issue if project data is aggregated, and it is hard to link individuals to the data. However, there are risks associated with smaller datasets where it might be possible to identify a cohort and/or an individual. In addition, information that is prohibited by the contract cannot be shared. Most contracts come with a confidentiality clause, but this clause tends to be vague. A potential solution is to agree upfront on what is commercially sensitive. This template can be a guide for outcomes contracts on what data can be made public.

When it comes to competition law, generally, it is allowed to share data that helps the market function effectively if the information is not commercially sensitive. Information that is already in the public domain cannot be commercially sensitive. Price-sensitive information (e.g., cost and outcomes pricing data) is more likely to be commercially sensitive. However, data that is commercially sensitive today, may not be in couple years’ time. The timing is completely dependent on the market’s functioning.

Outcomes-based contracts involve a mixture of parties, jurisdictions, and law and policy contexts. This ‘melange’ contributes to differences in commercial sensitivity concerns which need to be treated differently according to the specificities of contexts. One potential solution is for outcome payers to buy the data and acquire the right to release it. The clear acquisition and ownership secure the learning in outcomes contracting. Data is to be acquired and published as an output can be included at the start or added in at a later stage of a project’s contract.

There may be real costs associated with acquiring and publishing data. It might be time-consuming to figure out what data, how and when to release data. The INDIGO Data Dictionary, Social Impact Bond Contract Template, and resources from Creative Commons can be helpful tools in answering the questions posed above. It is important to consider the timing of data release. The risk of immediate scrutiny is not an irrational fear. It is often easier to publish data at the end of the project timeline. However, the published data needs to be accompanied by a qualitative story of the context. This could be in the form of case studies to qualitative evaluation. Without the narrative, data could be misinterpreted or misconstrued.

Pompy Sridhar, based at MSD for Mothers, told us that data sharing is all about joint learning for a sector’s growth. Lessons can be derived from microfinance where different stakeholders recognised the need to share data fairly and widely. In the health sector, there is so much data. However, one needs to find a way to communicate insights while respecting people’s privacy. Engagement to gather and publish more data could happen from the ground up by developing incentives and agreements as to what data is possible to collect, how the data should be shared, what insights are to be shared and to which stakeholders.

Towards data transparency

Despite the challenges of data sharing, experts identified a number of features which may help to facilitate greater transparency. Data sharing is easier once the project has finished, when there is clarity on who or which organisation owns the data, and when all stakeholders agree on the importance of the transparency agenda.

So, how about your completed projects? Although you may be busy with the live projects, can we build a legacy together of what you have done in the past? We will make sure others in the community will do so too, so that we can keep learning together. We hope everyone in the INDIGO community continues to engage in this conversation.