Exploring the Potential of Outcomes-Based Financing in Early Childhood Care and Education

“How can we fund early learning systems in a way that truly improves outcomes for children?”

“How can we fund early learning systems in a way that truly improves outcomes for children?”

That question framed the first webinar series on Outcomes-Based Financing (OBF) in Early Childhood Care and Education (ECCE), hosted by the Government Outcomes Lab (GO Lab) and NORRAG, in partnership with the Education Outcomes Fund (EOF).

The discussion brought together policymakers, funders, and practitioners from around the world, representing at least 13 countries, to explore how linking funding to measurable results could strengthen ECCE systems and ensure that more children get the best possible start in life.

Why ECCE matters and where the challenges lie

Mara Airoldi, Academic co-Director at the GO Lab, opened the session with a simple premise: “What we really care about is improving early childhood care and education.”

She introduced ECCE as a holistic concept covering children from birth to age eight, spanning education, health, nutrition, protection, and emotional and social development.

Despite widespread agreement that early learning is the foundation for lifelong success, many systems remain underfunded and fragmented. Only about 40% of children in low-income countries have access to organised ECCE, compared with around 80% in high-income countries[1]. Funding levels remain below 3% of education budgets, far short of the 10% benchmark recommended by UNESCO.

Mara identified five interlinked challenges facing ECCE systems today. She began with fragmented policy coordination noting how responsibilities are spread across education, health, and social protection sectors, making joint planning difficult and often leaving gaps in service delivery. She highlighted the diverse and uneven provision of services, pointing out that public, private, community, and faith-based providers all operate under varying standards, creating inconsistencies in quality.

Turning to the people who make these systems work, Mara underscored a third challenge: limited workforce capacity and recognition. Too many ECCE teachers, she said, remain under-trained and undervalued, a situation that undermines both quality and staff retention. The fourth challenge lay in measurement and data gaps; essential outcomes such as social-emotional skills and executive function are difficult to capture and rarely tracked systematically. Finally, she drew attention to the persistent equity and access gaps that continue to exclude disadvantaged children, those with disabilities, and those in rural areas from the opportunities they deserve.

Mara positioned outcomes-based financing (OBF) as one of several tools that could help governments and partners respond to these systemic challenges.

At its core, OBF links funding to verified results rather than pre-agreed inputs or activities. Instead of paying organisations simply to deliver a service, payments are released only when specific, measurable outcomes are achieved, such as children enrolling in quality early learning, improving developmental scores, or attending regularly.

By shifting the focus from how money is spent to what it achieves, OBF aims to:

- Align incentives across multiple actors, including governments, funders, and service providers, around a shared definition of success.

- Encourage flexibility and innovation, allowing providers to adapt their approaches to local contexts as long as they achieve agreed results.

- Improve accountability and transparency, by establishing clear, measurable outcomes and independent verification of results.

- Strengthen data systems, since reliable measurement becomes essential for payment and learning.

- Foster collaboration across ministries and sectors, creating shared outcome frameworks that cut through fragmentation.

In the context of ECCE, where progress depends on many interconnected factors (health, learning, nutrition, and family engagement) OBF can offer a structured way to coordinate these efforts. It does not replace traditional grants or public funding, but can complement them by incentivising performance and building an evidence base about what works best for young children.

Mara noted that while OBF is not a silver bullet, it offers a practical framework to link ambition with evidence and to focus resources on outcomes for children, rather than inputs or activities.

ECCE Outcomes Funds

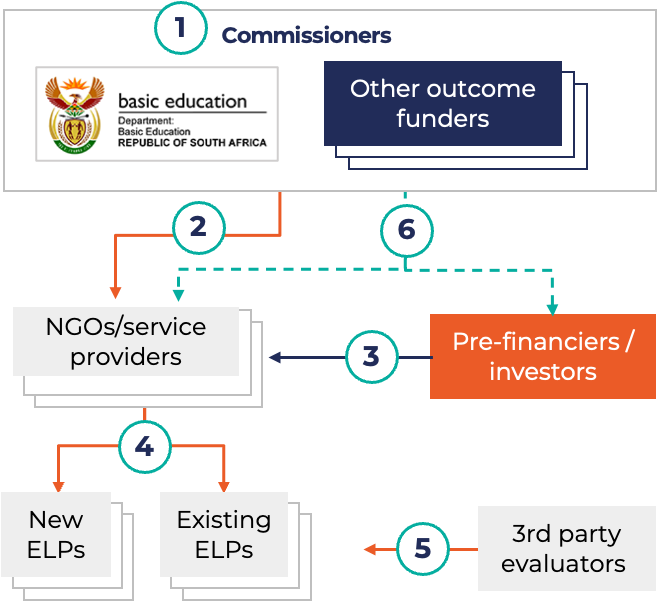

Adriana Balducci from the Education Outcomes Fund, introduced ECCE Outcomes Funds launching in Rwanda, Sierra Leone, and South Africa supported by EOF.

Each bring together governments, donors, and delivery partners to expand access to quality early learning for children. The funds channel pooled resources into hundreds of early childhood development (ECD) centres, with payments tied to measurable outcomes such as increased enrolment, improved quality standards, and demonstrable child development progress. In all three countries, funding is released only when results are independently verified, helping to ensure that investment translates directly into better outcomes for children.

Adriana highlighted several recurring sector challenges and opportunities:

- Fragmentation and coordination gaps: “Fragmentation is one of the key challenges in ECCE…the OBF model has helped support greater alignment across this large and complex sector”.

- Tight funding environments: OBF helps governments focus limited resources where they have the most impact, by linking disbursements to measurable results.

- Balancing access and quality: In Sierra Leone, payments are tied to bringing new early learning centres up to minimum quality standards, ensuring “scale doesn’t come at the expense of quality.”

- Inclusion and equity: In Rwanda, the government is interested in incentivising inclusion of children with disabilities, resulting in a premium payment for every child who both attends and demonstrates developmental progress.

- Government ownership: Governments co-design, co-manage, and co-fund every EOF programme. “It’s a strategy we use to ensure ownership and sustainability” Adriana said.

She described South Africa’s upcoming Outcomes Fund as particularly ambitious: co-funded by the Department of Basic Education and local philanthropies, it aims to reach 100,000 children across 1,000 early learning programmes, a first step toward universal ECCE by 2030.

Lessons from Bogotá

Siegrid Holler, Instiglio, brought a practitioner’s lens, sharing lessons from the City of Bogotá’s outcomes-based ECCE initiative, the first of its kind in Colombia.

The programme links part of local ECD centre funding to three measurable results:

- Attendance: ensuring regular participation by children.

- Retention: reducing dropout and improving continuity of care.

- Quality of service: assessed using tools developed by UNICEF, UNESCO, and the World Bank, focusing on interactions between carers, children, and their environment.

Participation was voluntary. Providers opting in could earn a performance bonus of around 5% of their contract value. It was noted that despite this modest financial incentive, the pilot helped shift attention toward defining and achieving tangible results, prompting richer conversations about what success in early learning actually means.

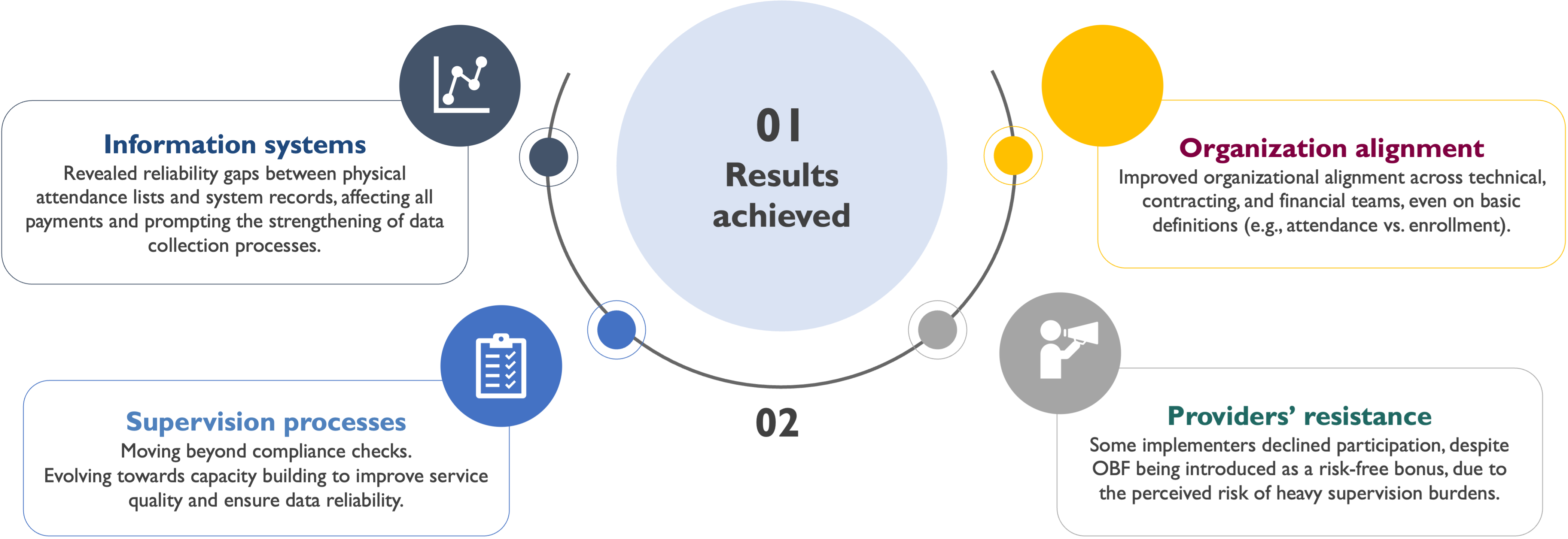

Key lessons from Bogotá include:

- Cross-departmental collaboration is essential: engaging technical, legal, and procurement teams early helps embed the approach in government systems.

- Simplify and clarify measurement: defining clear, shared indicators avoids confusion and builds trust.

- Reduce administrative burdens: providers feared extra bureaucracy; simplifying reporting and focusing on meaningful indicators increased buy-in.

- Data systems need investment: “We identified some issues in the data, some contradictions between the paper base and the operating system...it had to be strengthened”

- Supportive supervision, not control: shifting from compliance checks to coaching visits helped build provider capability and improve quality sustainably.

Siegrid noted that outcomes-based approaches can reveal the underlying barriers to progress and give both governments and providers room to learn, adapt, and strengthen their systems.

Play2Learn+

Claudia Lennon at 54 Reasons shared an on-the-ground perspective from the Play2Learn+ programme in Tasmania, a Payment by Outcomes contract jointly funded by Australia’s Department of Social Services and the Paul Ramsay Foundation.

Tasmania was chosen because it has the highest levels of child social exclusion in Australia, with only 48.9% of children developmentally on track (below the national average of 52.9%).

The programme focuses on children aged 3-4 from disadvantaged families, with payments linked to:

- Engaging 300 children who meet eligibility criteria (low childcare attendance, concession card holders).

- Attendance at 10 or more “Launching into Learning” sessions, which connect parents and children to schools.

- Improved kindergarten readiness scores on a government tool assessing developmental progress.

- Claudia reported encouraging progress: strong participation rates and above-target attendance at learning sessions. However, she noted that measuring developmental outcomes is complex and context-sensitive.

Her key lessons included:

- Plan for sustainability from day one: Claudia encouraged participants to think beyond short-term pilots and consider from the outset how successful models could be sustained and integrated into existing service systems.

- Strong partnerships matter: she reflected that outcomes-based contracting changes the relationship between funders and service providers, creating a more balanced partnership built on joint accountability for results.

- Be transparent with data: involve frontline staff in interpreting and responding to results.

- Adapt as you go: “Be bold in saying, we’ve actually got it wrong”.

- Keep children at the centre: “When things get tough… making sure that we keep the service recipients at the centre… is a really solid way of coming back to the table about why we’re all there.”

Audience insights and reflections

The session opened up to audience questions, sparking an exchange of ideas and reflections. One of the first questions centred on how programmes can ensure that funding truly reaches the children who need it most. Panellists shared a range of strategies, from setting clear eligibility criteria for low-income families, children with disabilities, and rural communities, to offering premium payments for harder-to-reach groups. They also highlighted the importance of thoughtful design, including evaluation protocols that prevent perverse incentives, such as unintentionally penalising lower-performing centres.

Speakers agreed that engaging finance ministries early is crucial for embedding OBF within national systems. Examples from Peru and South Africa illustrated how fiscal ministries can become powerful champions of the approach once they see its potential.

The conversation turned to the role of AI and digital tools in improving measurement. Adriana shared that EOF is exploring how AI could reduce evaluation costs and enhance real-time learning, while participants pointed to initiatives like Oxtrack in Nigeria and Kenya, which use AI to assess teacher quality and pedagogy.

Finally, Claudia reflected on the unique role of philanthropy as a bridge, helping to connect different parts of government and maintain a shared focus on long-term outcomes.

Looking ahead

Across the discussion, a consistent message emerged: OBF is not just a funding tool, it’s a learning framework. It encourages reflection, evidence use, and collaboration across sectors to improve how services are delivered.

Mara closed by thanking speakers and participants for an “honest, constructive dialogue” that reflects a growing movement. The evidence base, she noted, is still developing, but early experiences show OBF’s potential to mobilise funding, improve coordination, and embed accountability around what really matters: outcomes for children.

This session was the first in a two-part series. We invite you to join the next discussion will on 21 January, delving deeper into practical lessons from implementation (register here).

[1] UNESCO. (2024). Early childhood care and education: Landscape review 2010–2022. UNESCO.