- Development Impact Bond

- Agriculture and environment

- Employment and training

- Poverty reduction

- South America

Peru

5 mins

Asháninka – Peru Development Impact Bond

Last updated: 19 Oct 2021

The Asháninka impact bond was the first impact bond in Latin America. It was launched in 2015 and sought to support sustainable cocoa and coffee production within the Asháninka community, an indigenous community living in the Peruvian Amazon.

Project Location

Aligned SDGs

INDIGO Key facts and figures

-

INDIGO project

-

Commissioner

-

Intermediary

-

Investor

-

Provider

-

Evaluator

- Royal Tropical Institute (KIT)

-

Launch date

January 2015

-

Start of service provision

February 2015

-

Capital raised (minimum)

USD 110k

-

Service users

99

Target population

The target population included Asháninka families (typically 2 adults and 5 children). Indigenous Asháninka live near the Ene River in the Peruvian Amazon, and the intervention targets, specifically, the Kemito Ene producer’s association. The population was only considered if they paid their membership fees and were active members of Kemito Ene

The problem

The Asháninka are a group of indigenous people living near the Ene River in the Peruvian Amazon. They rely on agriculture for their livelihood. However, their production of cocoa and coffee, which accounts for most of their income, is not efficient due to post-harvest loss and leaf rust disease.

Better farming practices, as well as improved collection and post-harvest techniques, are key to increasing Asháninka’s monetary income, which they rely on to ensure education and health.

The solution

The DIB aimed to support sustainable cocoa and coffee production and marketing by indigenous Asháninka. The intervention was delivered by Rainforest Foundation UK (RFUK) with the help of its partner organisations in Peru. The intervention was focused on improving the collection and post-harvest techniques for cocoa, investment in marketing, promoting commercial agreements, controlling leaf rust disease and restoring growing plots, and, building nurseries for planting resistant varieties of coffee.

The DIB’s goal was twofold. First is to increase the productive output of coffee and cocoa by members of the Kemito Ene Producers' Association (KEA), a coalition of Asháninka farmers. Second is to develop and strengthen the production process itself - with an underlying aim to improve the livelihoods of KEA members and have a subsequent positive externality for the families and the broader community. The DIB was designed to be implemented over a relatively short period of time to enable a rapid evaluation of the idiosyncrasies inherent to the process and help determine whether this funding mechanism was effective in this context.

Source: Oroxom, R and Glassman, A. (2018) & KIT Royal Tropical Institute (2015).

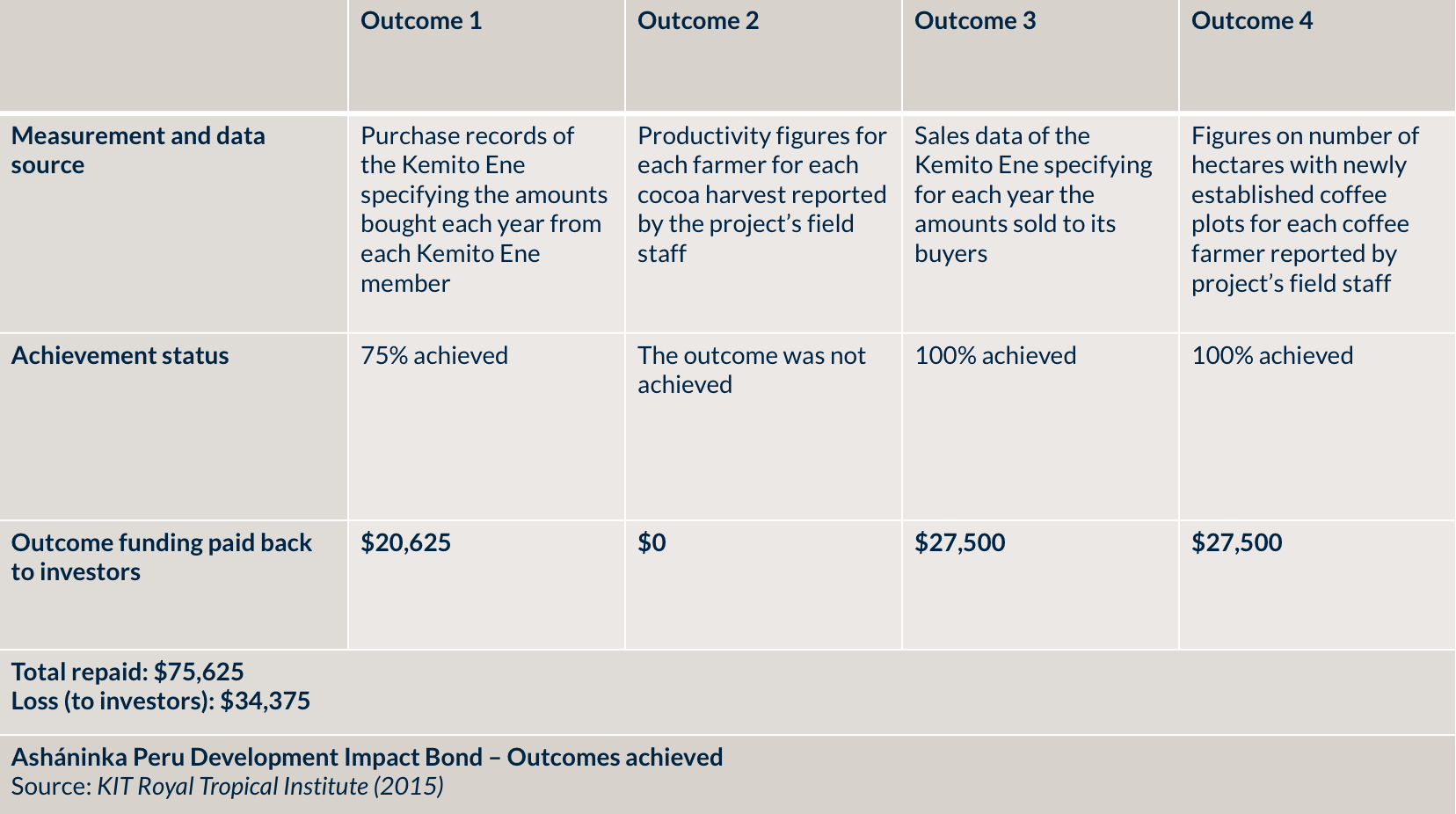

The impact

Out of a total of 99 members of KEA who participated in the project, 45 of them increased their sales by over 20%, by 2015 which represented a sale of 47,428 kg of cocoa to different buyers. This amount exceeded the target of 35 tons to be sold by KEA, initially set by the project. Furthermore, over than half of the farmers who participated in the project (62 out of the 99) were also able to increase their area of land, allowing for an improvement in the plantation of several coffee varieties.

Source: Source: KIT Royal Tropical Institute (2015).

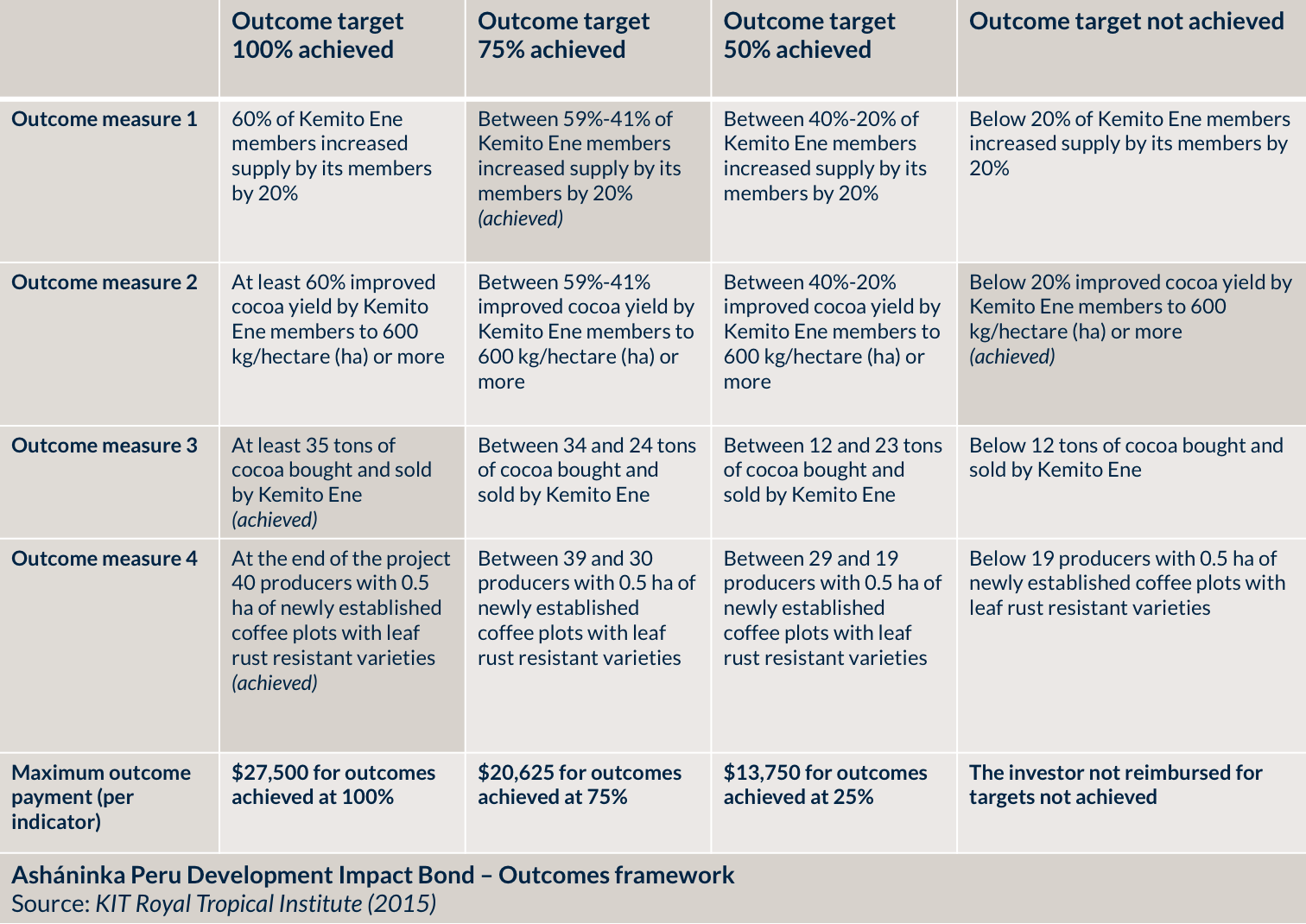

Outcomes framework

As explained in the KIT evaluation, the partners on the DIB project agreed that the total value of the DIB would not exceed $110,000 covering the outcome payment and all administrative, service and related fees and expenses.

The following results were agreed upon among all the parties involved, formulated as specific, objectively verifiable project performance indicators:

60% of Kemito Ene members increased their supply to the Association by at least 20% thereby improving their income received from Kemito Ene;

At least 60% of Kemito Ene members improved their cocoa yield to 600 kg/ha or more;

At least 35 tons of cocoa were bought and sold by Kemito Ene in the last year of the project;

At the end of the project, 40 producers have 0.5 ha of newly established coffee plots with leaf rust resistant varieties.

It was agreed among the parties to assign the same weight to each indicator, implying that each indicator represents a maximum of 25 percent of the maximum project budget assigned by the commissioner. This means each of the four outcome indicators represented a maximum of $27,500 of the maximum project investment of $110,000.

The repayment for each outcome was contingent upon meeting the required metric, which was divided across 3 levels (50%, 75%, and 100%). Thus, repayment began when the 50% target was achieved, and full repayment required meeting the 100% target for all four outcomes.

Source: KIT Royal Tropical Institute (2015).

Evaluation methodology

To assess the project’s results, KIT, as the evaluating partner, conducted a field mission visiting the project office in Satipo and project sites in Tabecharo and Rio Ene, Junin province, Peru.

The assessment drew upon both quantitative and qualitative data and research, including:

- Review of project documentation (including progress reports, field activity reports and publications);

- Meetings and discussions with the RFUK (project) team, both in the project office, during travel and at the field sites, mainly focusing on information and data collection and obtained results;

- Analyses of data sourced from the RFUK team;

- Field work: through direct observations at two project sites, one for coffee and one for cocoa;

- Focus group discussions: with coffee and cocoa farmers at the two project sites, involving women and men; and

- Informal interviews with female and male farmers and other stakeholders during the field visits.

Source: KIT Royal Tropical Institute (2015).

Timeline

-

December 2013

Baseline study commences.

The baseline was established at the end of December 2013. This meant that the terms of comparison and the definition of success were set in relation to this date. The impact achieved during the year of 2014, which was not considered to be part of the project, played a critical role in the success of achievement of impact metrics 1 and 4.

Source: KIT Royal Tropical Institute (2015).

-

July 2014

Feasibility study begins.

-

January 2015

Contract is signed.

-

February 2015

Service provision starts.

-

October 2015

Project is completed and service provision stops.

Project insights

Achievement of outcomes

The failure to meet the target for Outcome 2, increasing the cocoa yield to 600 kg per hectare, can be attributed to three challenges:

- The project team realised at the start of the project that the productivity figure collected in their baseline study (400 kg/ha) was inaccurate. The cocoa yield was significantly lower in their project areas, for a number of reasons such as low yielding varieties and suboptimal management practices;

- In the initial stages of the project, a severe pest called Mazorquero broke out which adversely impacted cocoa’s productivity; and

- The fertilisation programme adopted for the project by KEA would only see results (an increase in production, and yield) from 2016, after the intended end of the project timeline.

Sources: KIT (2015) & Oroxom and Glassman (2018).

- The project team realised at the start of the project that the productivity figure collected in their baseline study (400 kg/ha) was inaccurate. The cocoa yield was significantly lower in their project areas, for a number of reasons such as low yielding varieties and suboptimal management practices;

Strengthening outcomes and metric clarity

Upon evaluation, KIT noted that greater emphasis could have been placed on the initial formulation and precision of the indicators, which would have strengthened the clarity of intended results for all parties.

For example, the first indicator, which refers to an increase of 20% in supply, may be compared with a very low value (1kg to 1,2 kg), and still be regarded as success. The clear outline of measurable targets is often outlined as a pillar of successful impact bond design.

Source: KIT (2015).

The baseline

The Asháninka impact bond included a baseline that began at the end of 2013, and thus included an evolution over a longer timeframe than the project's duration, from January to October 2015.

There is uncertainty about how outcome variables evolved in the period between the baseline and the beginning of the intervention. Consequently, some of the effect in the results reported may not be attributable to the impact bond intervention itself.

Focus on results

Greater emphasis should have been placed on a results-driven focus to project design as the DIB allows for operating beyond some limits of conventional development projects. Conventional development projects typically have strict rules by donors regarding project design, approach, priority themes, reporting requirements, etc.

Source: Belt, J., Kuleshov, A. and Minneboo, E. (2017) & KIT (2015).

Interview with Aldo Soto, Rainforest Foundation UK

Contact details

References

Communication with Aldo Soto, Rainforest Foundation UK.

Rainforest Foundation UK (2014) Kemito Ene at Festival Press Release.

This case study was compiled by Maze – Decoding Impact.

Page last updated: September 2022

Downloads and Resources

Oroxom, Glassman and McDonald (2018) Structuring and Funding Development Impact Bonds for Health – Nine Lessons from Cameroon and Beyond

Download PDF