- Impact bond

- Employment and training

- Europe

Finland

6 mins

Kotouttamisen (KOTO) Social Impact Bond

Last updated: 26 Jan 2022

- Kotouttamisen (KOTO) Social Impact Bond

- SDGs and project locations

- INDIGO Key facts and figures

- Target population

- The problem

- The solution

- The impact

- Timeline

- Project insights

- Contact Details

- References

- Kotouttamisen (KOTO) Social Impact Bond

- SDGs and project locations

- INDIGO Key facts and figures

- Target population

- The problem

- The solution

- The impact

- Timeline

- Project insights

- Contact Details

- References

The Kotouttamisen (KOTO) Social Impact Bond was launched in 2017 to support the integration of migrants into Finnish society by helping immigrants find employment by linking tailored vocational and language training to shortages in the Finnish labour market.

Project Location

Aligned SDGs

INDIGO Key facts and figures

-

INDIGO project

-

Commissioner

-

Intermediary

-

Investor

-

Provider

-

Project administrator

- FIM Vaikuttavuussijoitukset Oy (formerly Epiqus Oy)

-

Launch date

January 2017

-

Start of service provision

2017

-

Duration

3 years

-

Capital raised (minimum)

EUR 14.30m

(USD 16.11m)

-

Cohort size (targeted)

2,500

Target population

Immigrants aged 17-63, who have been granted a residence permit on the basis of international protection and who have registered as unemployed job seekers at the Employment and Economic Development Office

The problem

Although Finland does not receive a large number of refugees overall, the relative rise in 2015 was noteworthy. According to Statistics Finland, over 30,000 new asylum seeker applications were received in 2015– ten times higher than the usual annual number. Not unlike some other European countries, this was met by concerns of an ‘islamization of society,’ a 26% rise in racially motivated hate crimes between 2011 and 2015, and the rise of far-right factions with anti-immigrant sentiments. Several thousand refugees have been deported in recent years amid ongoing amendments to application rules and tightening of asylum procedures.

Although Finland’s success as one of the world’s leading welfare states provides great support to both asylum seekers and those granted asylum, there are significant disparities in employment between migrants and native-born Finns (OECD, 2017). High unemployment rates have raised further concerns around integration as well as public expenditure.

The solution

To support the integration of migrants into Finnish society the Finnish Ministry of Economic Affairs and Employment implemented an employment programme using a social impact bond (SIB) approach. Launched in 2017, the KOTO SIB aims to provide jobs for 2,500 migrants over the course of the three-year implementation period. The KOTO SIB supports immigrants find employment by linking tailored vocational and language training to shortages in the Finnish labour market. These jobs are primarily in manufacturing, construction, trade and services, where the shortage of skilled workers is particularly acute.

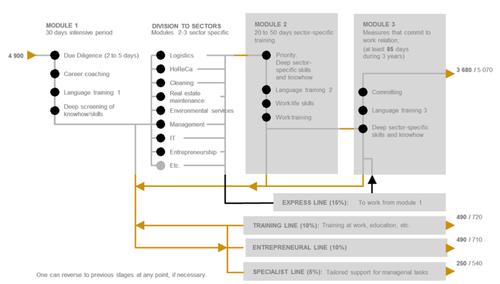

The KOTO SIB is designed to encompass language training, general career coaching, as well as more specific work skills. The process is structured around three modules:

- Module 1 features due diligence, career coaching, language training level 1 and a deep screening of skills over an intensive period of 30 days.

- Module 2 provides 20 to 50 days of sector specific training, with a focus on sector specific skills, in addition to language training level 2, work-life skills and more specific work training.

- Module 3 is completed in 85 days over three years based on commitment to work relationships, language training level 3 and deep sector-specific skills.

There are also four ‘lines’, or programme variations, that run in parallel to the three modules. The Express Line transitions the individual from module 1 to work directly. The Training Line adds training at work and further education. Whereas the Entrepreneurial and Specialist lines also offer tailored support for entrepreneurship and managerial tasks, respectively.

Furthermore, the project brings together a cross-sector collaboration while using an outcomes contract and social investment. Diverse stakeholders from the private, public, and non-profit sectors are aligned around shared objectives and collaborate closely to achieve them together. Investors provide upfront capital and take on the risk of the project. Meanwhile, the Finnish government is expected to pay only when pre-agreed outcomes are achieved.

The impact

In October 2020, preliminary results were published by the Ministry of Economic Affairs and Employment of Finland. A total of 2200 immigrants have participated in the SIB, of which about 1100 had gained employment by October 2020. 1700 participants received training for more than 70 days- a key metric within the project. It is reported that more than 50% of participants who completed the training were successfully employed.

The most prolific employers were from the logistics, hotel and restaurant, cleaning, construction, financial administration, information technology and manufacturing industry sectors.

However, final results are yet to be determined by an external evaluator. In an evaluation planned for 2021-2022, the evaluator will compare the SIB participants’ tax payments and unemployment benefits to those of the control group. The SIB will be considered a ‘success’ if the participants are found to have paid more taxes and received fewer unemployment benefits than the control group. Final results of the RCT are expected in early 2023.

Outcomes framework

The impact will be evaluated through a randomised controlled trial (RCT) with the primary outcome measure being the differences in tax collections and unemployment benefits between control and intervention groups. 70% of service users are randomised into the intervention and the remaining 30% are randomised into the control group.

The hypothesis is that those immigrants who benefit from KOTO SIB (the intervention group) will be paid lower unemployment benefits than immigrants not involved (the control group) while paying more in taxes. This should result in savings for the government, who will then pay 50% of any money saved directly back into the fund (to investors).

While ultimate outcome payments are based on the above measures, the projects also tracks and reports on the number of individuals trained and supported into employment. A bonus of €1500 will be paid to investors for each immigrant who has achieved 70 days of training (as outcomes payments). This amount is half of the market price for the training service, which leads to further savings for the government.

According to the project’s estimates, the government could potentially save €35 - 40 million over the 6-year period (including the pilot phase), or €70 million in the “best” case scenario.

| Outcomes | Metrics | Outcome Target | Evidence | Preliminary results (Oct 2020) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Increased employment of refugees & immigrants | Support refugees & immigrants into employment | 2500 individuals | Administrative data | 1100 |

| Training for refugees and immigrants |

70 days of training completed for each refugee/immigrant |

2500 individuals | Administrative data | 1700 |

| Increased tax collections | Difference in tax payments between treatment group and control group |

Higher tax collections from treatment group |

RCT | N/A |

|

Reduced unemployment benefits |

Difference in unemployment benefit claims between treatment group and control group | Lower unemployment benefit claims from treatment group | RCT | N/A |

Timeline

-

January 2017

SIB launched

-

2017 - 2020

Service delivery period

-

2020-2023

Monitoring period

-

2023

Final results of RCT announced and outcome payments to be paid out

Project insights

An outcomes-based approach can allow greater flexibility and innovation in supporting refugees and migrants

In Finland, the government would traditionally pay for inputs and activities (e.g., the number of service users, number of courses, number of hours of training). But with the outcomes or results focus of the social impact bond, the focus instead shifted to providing jobs and speeding up this process of finding a job.

Whereas before refugees and migrants might have gone through almost 5 years of training before entering the job market, the SIB reduced this to just a few months. Service providers could now follow a ‘place-then-train’ model, offering more flexible training and employment services. In addition, they could hire coaches who were best suited to the job (e.g., those with similar cultural and linguistic backgrounds as the service users) rather than having to adhere to strict requirements on qualifications and experience for these coaches.

Most importantly, as this was a pilot, there were multiple aspects that needed to be tweaked over time. This included the expansion of the cohort to include immigrants, addressing the length of training to accommodate refugee preferences and needs, and customisation of the service. Due to the focus on outcomes and results and the flexibility that this allowed the service provider, these changes were successfully incorporated into the project.

Referral mechanisms and contracting must be planned early

The biggest challenge in the project was the low number of referrals of refugees and participants into the service in the first year. This was because referral mechanisms had not been established from the beginning and were not written into formal contracts.

While the responsibility for referrals lay with employment offices (“TE offices,” which operate at a municipality level), these were detached from the project’s development process and had little contact with other stakeholders. As a result of low referrals, engagement and outcomes within the project were adversely impacted.

Going forward, a key recommendation is to co-design projects and plan referral mechanisms early on. Projects must decide and clearly communicate referral pathways, eligibility criteria, and ideally reflect this into formal contracts. They must also think through ways of protecting service providers and countering underperformance if these don’t come through as planned.

User voice and lived experience should be incorporated to understand refugees’ and migrants’ differing needs

While it may be easy for a project to set a certain aim around getting service users into employment very quickly, this might not always be feasible or indeed even a preference for refugees and migrants.

As refugees have often experienced trauma, undertaken long journeys and arrived in a foreign country where they don’t always speak the language, they might not be prepared to be launched straight into the job market. They might still be finding their bearings and settling in, or dealing with protracted asylum processes, which might affect their readiness to work.

In addition, service users’ needs are heavily influenced by their age and their family status. Young refugees and migrants with no family responsibilities may prefer to go into education first, including language training. However, older service users and those supporting dependents might be keen to get a job as quickly as possible rather than spending time in the classroom. Others still might not want to stay in that country and might be planning to either go back or move on to a different country.

It is therefore crucial to understand these different needs and motivations before designing the service and cohort, as these have a direct impact on engagement and outcomes. It is also key to build in some flexibility in the service so that these different motivations can be catered to, and refugees can be helped in the best way possible. An outcomes-based contract is one way of enabling this flexibility and customisation.

Evaluation should balance rigour and practical considerations

The KOTO SIB is evaluated through a randomised controlled trial (RCT), which is often upheld as the ‘gold standard’ in research and evaluation. However, several stakeholders found the RCT challenging to work with, especially as this meant some participants would be randomised into the control group and therefore ‘deprived’ of the service.

RCTs can be expensive and involve long timescales. Expanding the service before the end of the monitoring period could jeopardise the RCT’s design and make it difficult to attribute impact. As results for the RCT are not expected until 2023, scaling the service to new cohorts and geographies is not possible in the meantime.

Finally, while using measurable and quantifiable outcomes is important in an outcomes-based approach, stakeholders also recommended capturing softer, more qualitative outcomes in future projects. These can help provide additional context around an individual’s wellbeing and progress.