Families & fortunes: the importance of stakeholder alignment when working with families at scale

Sam Magne from The National Lottery Community Fund reflects on its latest report from the Ecorys/ATQ evaluation of the Commissioning Better Outcomes programme (CBO) - and on the lynch pin-role that social workers find themselves in, in an ambitious plan to make specialist family services available, pan-London wide, to children on the edge of care.

Sam Magne from The National Lottery Community Fund reflects on its latest report from the Ecorys/ATQ evaluation of the Commissioning Better Outcomes programme (CBO) - and on the lynch pin-role that social workers find themselves in, in an ambitious plan to make specialist family services available, pan-London wide, to children on the edge of care.

You may have heard about the study just launched by the Competition and Markets Authority. It will investigate concerns flagged by a Local Government Association report, which highlighted large, private-equity backed firms increasing their dominance of the children’s care-home market. But when it comes to initiatives backed by social investment that seek to prevent children from ending up in care in the first place, it’s important to ensure the sheep aren’t mixed up with the goats of the bigger CMA picture.

And so in this blog, we get a glimpse of why it’s essential that actors at the frontline of edge-of-care work have transparent insight into how good money design can serve their systems-changing initiatives, if existing queasiness among local government and social work teams are not to be quickened about socially invested ‘impact-first’ finance initiatives. And we look at how social workers are key to making it all work well.

Helping children at scale

In our evaluators’ kick-off visit to the pan-London Positive Family Partnership (PFP) initiative, we hear how a group of councils clubbed together to commission this edge-of-care service, on a Payment by Results (PbR) basis, with the upfront costs financed by social investment intermediary – Bridges Outcomes Partnerships. BOP’s finance is backed by – wait for it – a local government pension pot, among other sources including charitable foundations and dormant accounts. But despite the alignment of such interests, BOP has been at pains to play down the role of the finance, preferring to call the deal a Social Outcomes Contract (SOC) rather than a Social Impact Bond (SIB). Personally, I think both names only serve to hide a potentially powerful scaling and flexibility function which the social investment helpfully promises to play in this arrangement.

I won’t dwell here on the fascinating insights about the PFP intervention itself which are set out in the report – save to mention that it works flexibly with both Functional Family Therapy (FFT) and Multi Systemic Therapy (MST) evidence-based methods. The goal is to keep children out of care for as long as possible, judged by each 7-day period for which an eligible child remains out of care over 2 years.

Instead, let’s look at what the contracting mechanism is intended to do for the intervention and its commissioners. On the flexibility point - the finance enables the teams to spot and implement opportunities for enhancing PFP’s chances of achieving its goal for children. (That’s especially interesting, and something for the next blog on PFP). But the primary function of the finance is to set the service up to work at scale.

Practical stumbling blocks

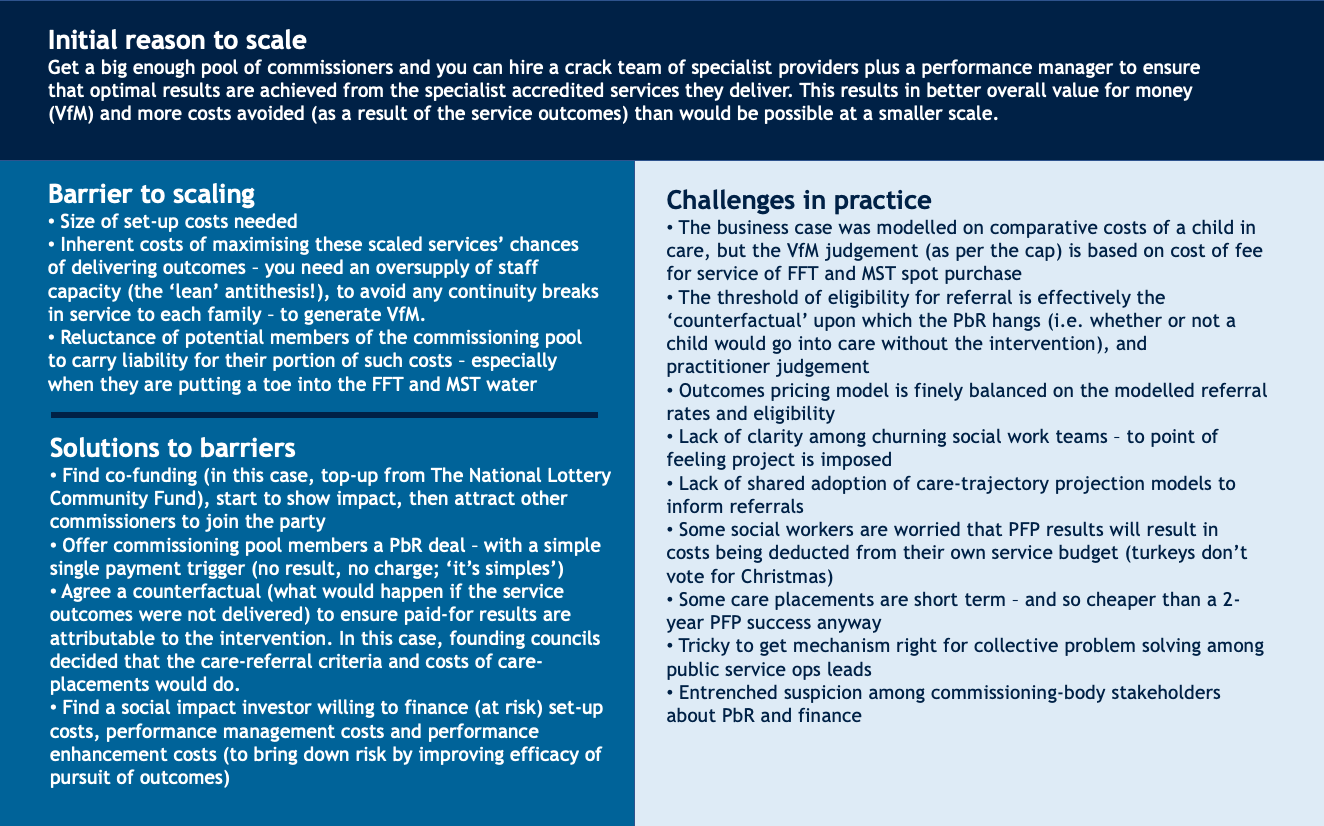

The graphic below summarises the case for scaling – and the challenges of implementing the logic in practice. The question it reveals as being pivotal for the SOC arrangement is: does the budgetary perspective of the social workers - who are charged with administering the project’s vision by acting as gatekeepers to the service - match up with the designers’ perspective on which the financing of the service was originally modelled?

Such practical challenges faced by the SIB have resulted in referral hesitancies among some boroughs’ frontline staff, prompting the following reflections from those involved:

“While the contracted commissioners are much more realising that this [the SOC] is a benefit because you only pay for the ones that are successful, the people that hold the budget and social care are thinking differently. It has to come out of their budget, so they think ‘it needs to be somebody that definitely will go into care. Otherwise, I have to save money because it comes out of my budget.’” – Provider (PFP)

“I think other authorities, and I would say the ones that are being more successful, are referring slightly earlier [than us]. So they are looking at those children that are on the trajectory of care…. So the professional judgement is: we know where the family is going, they are going to end up going to that edge of care panel, but they just get to them that little bit earlier, so that’s what we’re trying to encourage here really.” – Commissioner

Want to read the report?

Getting everyone on the same page

As the evaluators report, the simple payment trigger is intended to keep everyone focused on a common goal, while keeping the complexity of the finance and the commissioning co-op arrangements in the background. But the devil is always in the detail and the early part of the PFP story shows that the lynchpin of success is whether folks on the ground feel they are on the same page as the design level stakeholders. As in many SIBs/SOCs, the emphasis rests on the VfM benefits that the arrangement will bring through scaling and performance; but unless you get the gate-keeping right, neither of those gains can materialise.

The difficulty this initiative faced at that starting gate hung on the calibration of the threshold of need for referring a child. Getting that right is critical to the credibility of the PbR arrangement itself, as it acts as a quasi-counterfactual against which to claim the project is delivering each result. Get it wrong, and the whole impact-first finance system that backs the SIB faces undue extra risk.

The next two evaluation visits will look closer at PFP’s careful balancing act and, at whether selecting PbR (and the finance to support it) as the solution for barriers to scaling and to achieving VfM objectives, is holding up as the most suitable tool to pull from the commissioning box. In the meantime, an allied question in a Policy Evaluation & Research Unit paper hangs in the air, which perhaps the CMA study could also usefully reflect on: if front-line social workers and their clients were to become more deeply involved in the design and scenario testing of future contracting and finance mechanisms for care and edge-of-care services, what kind of people-led arrangements might we get next?

Samantha Magne

Samantha Magne