Learning outcomes at all costs – is outcomes-based funding in the education sector a smart buy?

Posted:

9 Mar 2022, 10:30 a.m.

Author:

-

Laura Bonsaver

Policy and Engagement Associate

Laura Bonsaver

Policy and Engagement Associate

Topics:

Impact bonds, Cross-sector partnerships and collaboration, Outcomes-based approachesPolicy areas:

EducationTypes:

Engaging with Evidence series

In this article, Laura Bonsaver highlights key learnings that emerged from our latest Engaging with Evidence session on the use and cost-effectiveness of outcomes-based funding in the education sector.

In this article, Laura Bonsaver highlights key learnings that emerged from our latest Engaging with Evidence session on the use and cost-effectiveness of outcomes-based funding in the education sector.

The state of global education – a sobering picture

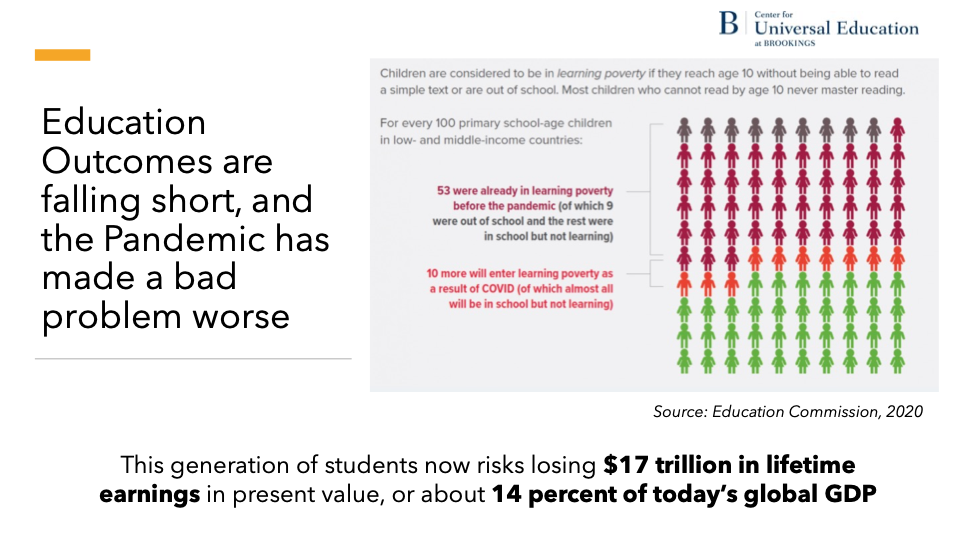

Even before the outbreak of Covid-19, we were facing a global learning crisis. Two years on, the pandemic has disrupted education systems around the world and exacerbated existing issues. With growing evidence that school closures have led to a loss in foundational skills and increased levels of illiteracy amongst school children (according to UNESCO, almost 60 million children globally were still out of school in 2021), organisations across the world have been rallying together to design and develop new interventions to help keep young learners from slipping through the net.

Building on their partnerships, organisations are having to work hard to innovate and adapt programmes to suit children’s evolving needs. Additionally, financial pressures increase the need to make the best use of limited resources. It is vital that we understand the most cost-effective ways to deliver interventions.

Can outcomes-based contracting step up to this challenge?

At our webinar last month, Dr Emily Gustafsson-Wright, Senior Fellow at the Brookings Institution, argued that while outcomes-based contracting might not be the panacea across all contexts, adopting a greater focus on outcomes could improve the likelihood of addressing the learning crisis.

According to our impact bond dataset, there are currently 30 impact bonds across the world working in the education sector. With flexibility central to these innovative financing models, many organisations have been able to adapt and tailor interventions to learner and contextual needs. Grace Wood, Education Adviser for FCDO Ghana, saw similar benefits from a government perspective. By aligning financing to results and focusing on the end outcomes for children, governments and partner organisations were able to encourage and incentivise more innovation and creativity than with alternative financing models. Particularly in the uncertain context of the pandemic, the flexibility of outcomes-focused programmes provided space to understand how to improve efficiency in real time and thus increase value for money.

Panellists also made a case for the approach helping to strengthen ecosystems in the long-term. Miléna Castellnou, Chief Programs Officer at the Education Outcomes Fund (EOF), explained that on top of the direct improved learning outcomes, outcomes-based contracting can help change mindsets in government. The approach can encourage them to have a more outcomes-focused approach, and thus bring systemic change to broader programme design. In addition, testing several interventions and putting a greater emphasis on data collection can improve internal capabilities. It equips governments with a greater understanding of what works throughout programme delivery and indicates which programmes they could scale up in future.

How cost-effective are these programmes?

While many intervention-focused evaluations have been published on outcomes-based projects around the world, there are still very few economic evaluations of the funding mechanism. However, Dalberg Associates Dayoung Lee and Gagandeep Nanda recently undertook research to understand the level of impact achieved through outcomes-based funding, and at what cost.

With the Quality Education India Development Impact Bond soon coming to an end, Dayoung and Gagan set out to draw broader lessons on the outcomes-based financing ecosystem in education in India, as well as to understand the cost-effectiveness of education interventions more broadly. In other words, does outcomes-based financing pay off? Is it worth the additional costs involved? How do we reduce these costs in future projects? And what types of interventions should policymakers and funders look to invest in going forward?

Leveraging rich data collected on impact, they explored twenty-three programmes across four different funding models. Eventually, they narrowed down to a carefully selected group of six interventions, and found 50% higher learning outcomes achieved for outcomes-based funding compared to non-results settings for same interventions, with costs no higher. With these encouraging results, Dayoung concluded that the considerably higher outcomes combined with little change in costs made the model a “smart buy”. They found that the flexibility to pivot the interventions proved cost-effective as it allowed freedom to stop spending money unnecessarily on ineffective activities.

Gagan and Dayoung emphasised that these results are not limited to impact bonds, but several types of “smart contracting” with a focus on outcomes. They were also able to identify what helped drive success in some outcomes-focused programmes, such as carefully selecting partners based on past performance and starting with small contracts before scaling them up over time. Going forward, Gagan hopes that more funding will be deployed to support intervention types with proven cost effectiveness. Overall, Gagan and Dayoung felt that interventions using outcomes-based funding were able to achieve meaningful gains at a time of urgent crisis in the education sector.

What next?

At the end of the session, panellists agreed that these insights are not limited to just India or the education sector but apply to outcomes-based contracting more broadly. Miléna Castellnou from the Education Outcomes Fund, argued that emerging evidence on cost and impact is critical and offers proof of concept of mechanism - something many evaluations do not address.

Looking ahead, Gagan emphasised the continuing need to bolster our evidence around outcomes-based contracting. Finding data for their research was challenging, and there is a clear need for better access to data to support a stronger evidence base.

There is also still the need for outcomes-based funding readiness amongst providers and within governments to ensure they can adapt and focus on outcomes – again, including but not limited to the use of impact bonds. Emily from Brookings added that to make this change, it is vital to have champions within government driving this shift in mindset and for pre-existing tools to be shared to avoid the expensive reinvention of the wheel. We will be exploring ecosystem and service provider readiness at our next Engaging with Evidence webinar in April.

Tackling the global education crisis poses a huge challenge, but supported by the right evidence and approaches, outcomes-based contracting could provide a valuable part of the solution.