Value, it’s not just in the numbers

Posted:

8 Jul 2019, 5:08 p.m.

Authors:

-

Leigh Crowley

Project Associate

Leigh Crowley

Project Associate

-

Mehdi Shiva

Economist

Mehdi Shiva

Economist

Topics:

MeasurementPolicy areas:

Health and wellbeing, Employment and trainingHere at the Government Outcomes Lab we concern ourselves with improving socio-economic outcomes for people with complex social needs. Appropriate policy responses to people with complex social needs is challenging and potentially financially costly. For example, the homeless not only have a lack of housing, but their needs may include any combination of the following: substance misuse, mental health conditions, offending behaviour, primary care needs, unemployment issues and learning disabilities. In short, there is no silver bullet to improve the outcomes for this cohort.

In the first instance, our willingness to pay (WTP) to support this cohort may largely be driven by the financial cost of providing a service – will the service cost ultimately be compensated by long-term financial costs if the service is not delivered? If the answer to this question is yes there is a financial case to proceed. However, if the answer is no the support offered to this cohort will have to reach beyond finance analyses to identify broader sense of ‘value’.

It is in this grey area – where the financial case is less clear – that moral considerations of the extent to which this policy issue or cohort matters to a society comes to the fore. In an attempt to close this grey area this blog will incorporate Jonathan Wolff’s (2018) conception of the ‘engaged philosopher’ into the policy appraisal process alongside data and economic analysis. The rationale for incorporating the engaged philosopher methodology is to support evaluations of possible policy responses by establishing and weighing the moral arguments of whether a policy is justified.

Do we ‘value’ our problem?

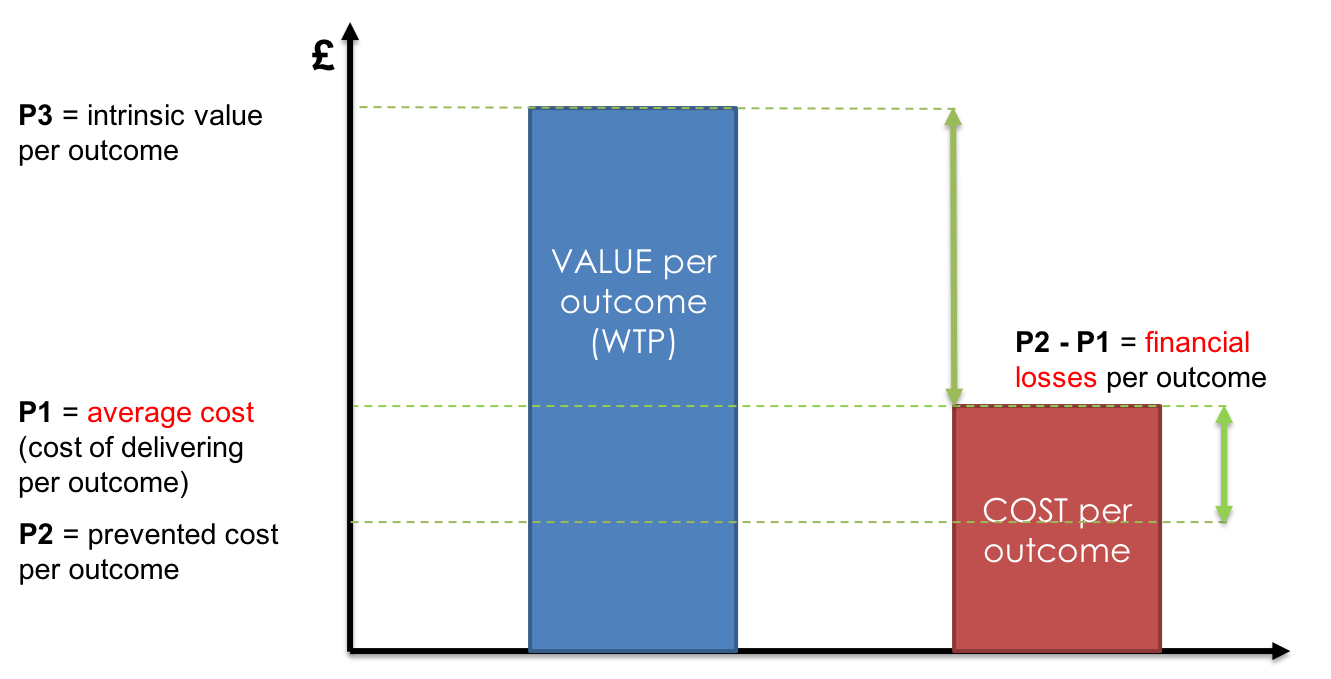

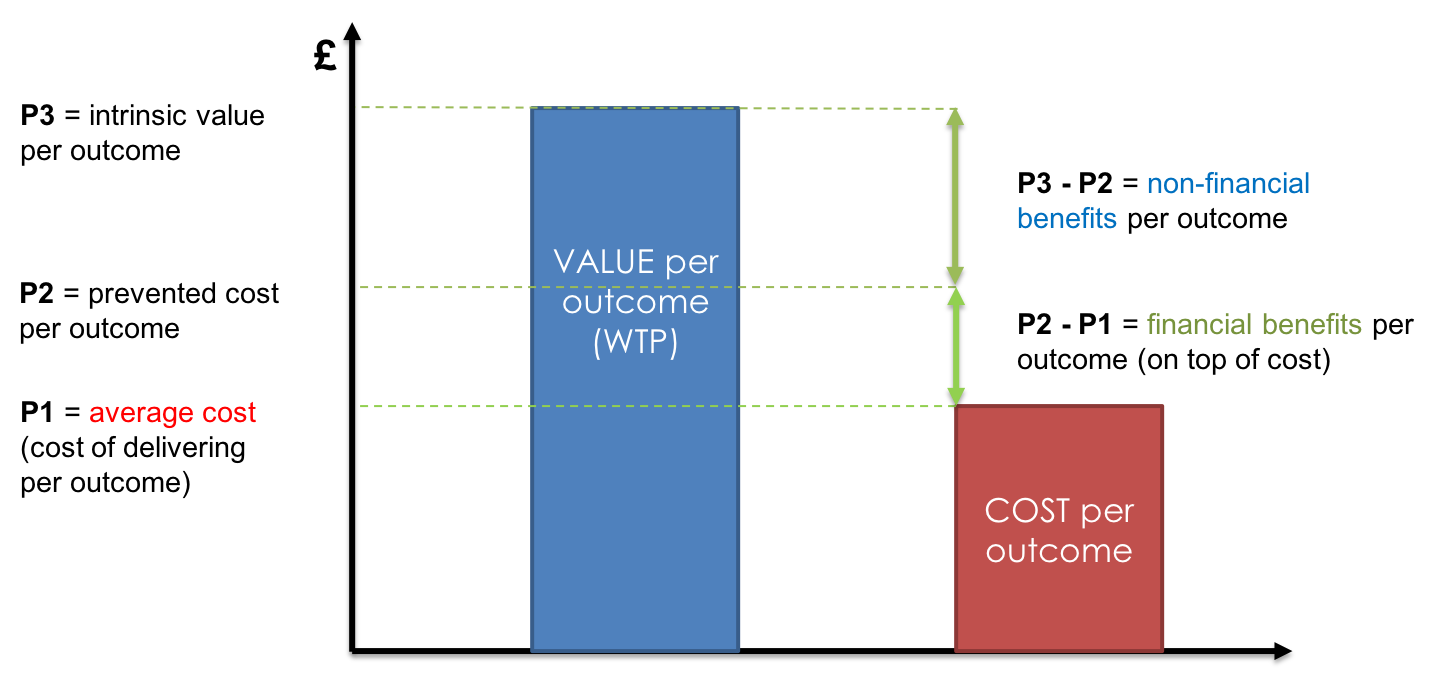

For any given policy problem our desire to find a remedy can be attributed to the ‘value’ we attach to eliminating - or at least reducing - it. A data-driven approach to a feasibility assessment of a particular policy response will utilise tools such as 'cost-benefit analysis' or 'cost-effective analysis' to determine the expected costs and benefits. These tools enable us to not only capture the prevented financial and non-financial costs, but also the ‘intrinsic value’ of policy issues to society. Our pricing outcomes guide recommends two approaches to measure and monitories benefits (benefits being a proxy of value). The ‘intrinsic value’ of an outcome is the amount that society values a particular outcome. And ‘prevented costs’ attempt to measure fiscal savings delivered by the outcome to the ultimate payer of service provision.

The foundations of economic theory indicate that a transaction will only take place if WTP surpasses the cost of delivering services (Figure 1). However, how might we respond when the cost of delivering a desired outcome is greater than financial savings accrued by the final payer of the service, but less than the benefits to the wider society (Figure 2)? For instance, returning to our earlier example of supporting the homeless, net financial benefit estimates of the Supporting People programme is around zero.

See the figures below that are taken from our pricing outcomes guide.

What the numbers alone don’t tell us

Even when the cost of delivering a service to the homeless is higher than the predicted savings there can still be a strong moral imperative to provide support despite financial losses. It is in these muddy waters, where economic analysis and moral considerations mix, that the skillset of the engaged philosopher is able to support. The engaged philosopher is able to identify and articulate the moral dilemmas that underlay policy debates, and potentially chart a path forward with the identification and evaluation of possible solutions.

Before possible policy responses to homelessness can be considered comparisons across time and space should be used to develop an understanding of how the problem came into being, additionally comparisons can help prevent the same mistakes being repeated. Economists approach this task by building data models that attempt explain trends based upon analysis of past policy outcomes, while an engaged philosopher seeks to provide a deeper contextual understanding of homelessness causes and consequences. Wolff cautions that even when a problem is well-known “real understanding requires an appreciation of not just what is being publicised in the headlines, but the underlying position regarding law and regulations, as well as facts of behaviour”. Failure to fully appreciate the issue at hand will ultimately lead to bad policies. By cutting through messy political debates and potentially simplified economic analyses the engaged philosopher is able to clearly articulate the current state of play as well as the underlaying political and moral arguments.

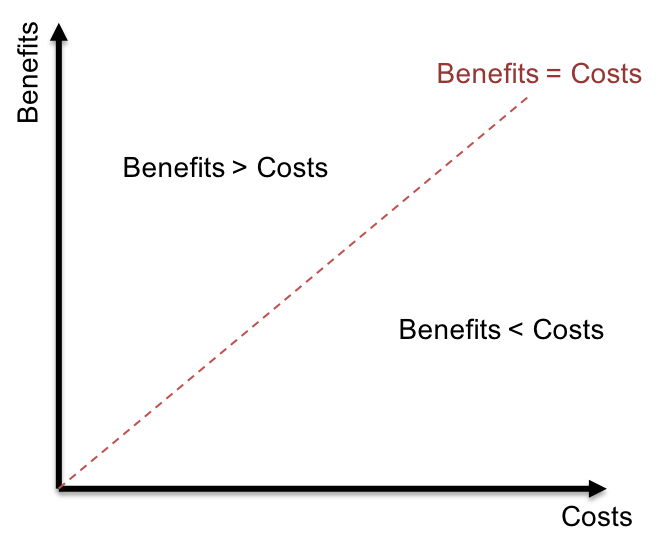

The insights gained from comparisons can be used to develop a menu of possible policy responses to homelessness. Though, like with any appetising menu, it is very difficult to decide what course to take, therefore we will want to appraise the ‘value’ of possible solutions. Economic analysis, such as benefit to cost ratio (Figure 3), is an important consideration for policy makers when they are deciding how best to allocate scarce resources. However, this analysis is unlikely to be the determining factor when benefit is less than cost, as is potentially the case with homeless people. The engaged philosopher can support evaluations of possible solutions by establishing and weighing the moral arguments of whether a policy is justified. The engaged philosopher informs policy debates by using their acquired knowledge to investigate a specific aspect of the policy debate in a level of detail and clarity that they would not have been pursued if they thought it was only one consideration among many, and then is able bring these ‘one-eyed’ considerations into the decision-making process.

An engaged philosopher can make a significant contribution to the policy process by increasing the awareness of the moral arguments underpinning distributive justice. This is because data alone is unable to tell us whether a policy ought to be statutory or non-statutory. For example, support to homeless, due to high costs and low benefits, might not be highlighted as a priority for politicians, but wider society may place a high moral value on supporting them, in which case statutory legislation is the appropriate response. Therefore, policy making would be well served by incorporating both data and philosophical considerations into the design process.

References

Wolff, J. (2018). Method in Philosophy and Public Policy: Applied Philosophy versus Engaged Philosophy. In A. Lever, and A. Poama, (Eds). The Routledge Handbook of Ethics and Public Policy. London: Routledge.