Awarding outcomes-based contracts

This guide explores outcomes contracts. It offers pointers on procurement and engagement and highlights ‘stumble steps’ to watch when closing the deal.

Overview

57 minute read

Awarding the contract for an impact bond is a complex topic that can vary across different countries. One impact bond will usually have multiple contracts between the various stakeholders involved, but this guide will focus on the ‘outcomes contract’. The ‘outcomes contract’ will set out the terms for when payment is made.

Impact bonds are new and complex ways of addressing social issues. There will be a number of differences between awarding a traditional contract and awarding the outcome contract that underpins an impact bond. These differences occur throughout the procurement process, from initial engagement with the market to closing the deal.

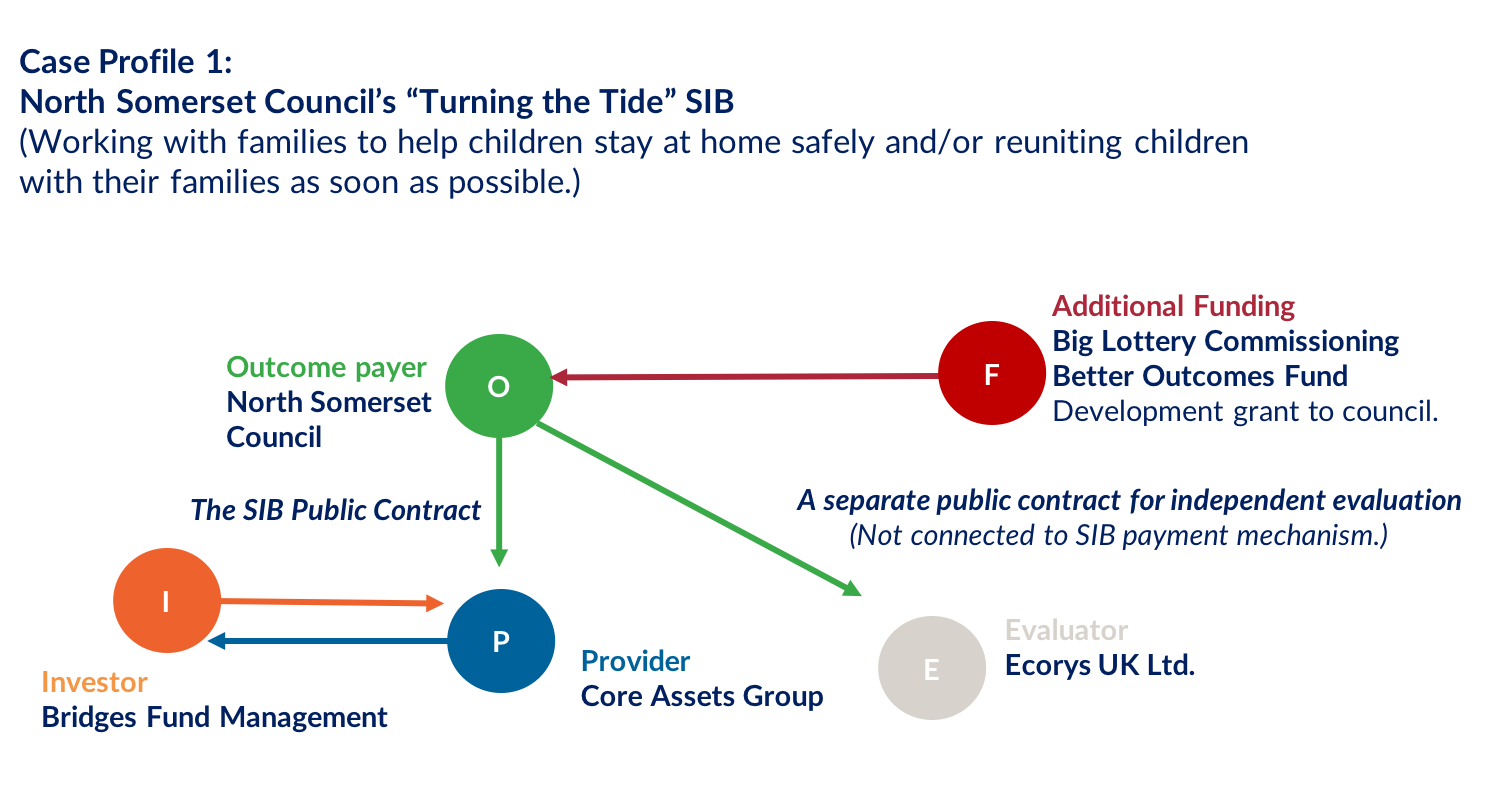

One major difference is the parties involved. Outcome payers, providers, investors, and a range of intermediaries may take part, and the relationship between them can be structured in a range of ways.

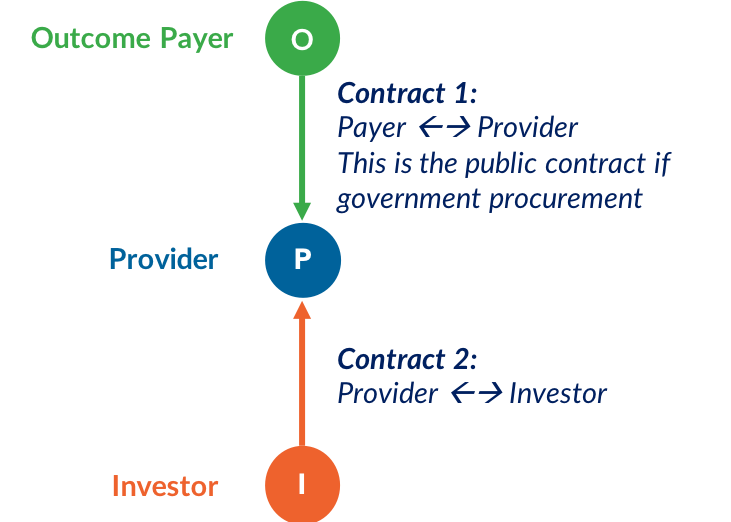

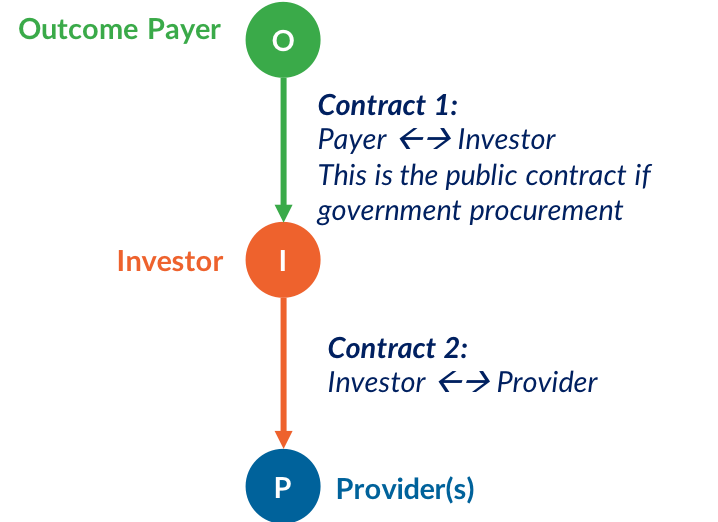

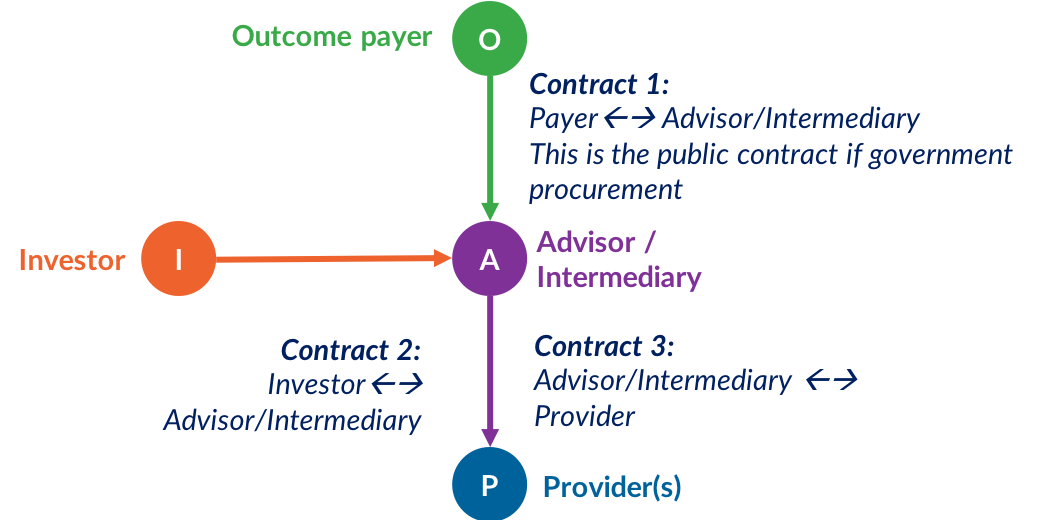

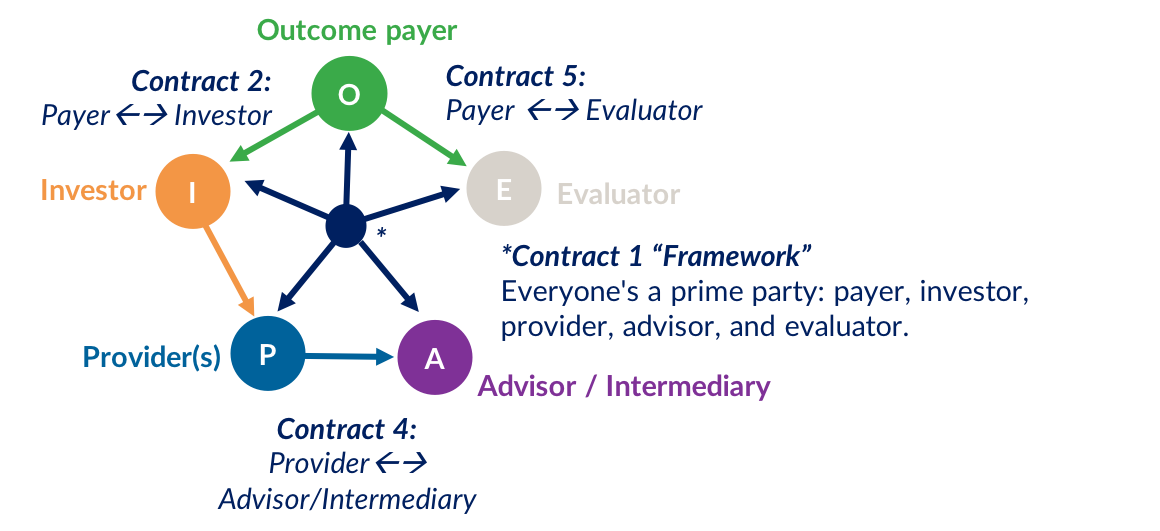

The primary outcomes contract may be between the outcome payer and provider, investor or an intermediary, or it may be a multiparty contract that incorporates all of them.

Outcome payers and investors may also differ in how much they want to participate in the contract, on a spectrum from active to passive.

Pointers for procurement and engagement

When developing an impact bond, the market and how you engage with it will be different, but the following pointers may help you to navigate the procurement process more effectively.

- Impact bond with friends. Outcome payers can collaborate in a number of ways, co-contracting to share costs and reach more beneficiaries, and learning from the experience of others.

- Widen market engagement. Outcome payers should engage with potential providers and investors early and often to understand and develop the market for impact bonds.

- Be flexible about how outcomes are achieved. Specifications should define outcomes, but not how they should be achieved (except for minimum service standards to protect beneficiaries).

- Secure the strategic benefits. Evaluations, data sharing and transparency help the outcome payer (and others) learn from what worked and retain capacity.

- Engage with service users and their representatives. Consult with service users and involve them throughout procurement and delivery.

Structuring an outcomes contract

While broad advice is helpful, it is also helpful to have more concrete examples of how to structure an outcomes contract. The UK SIB Template Contract and the Educate Girls ‘Framework’ Contract may provide a useful starting point, and in particular may be preferable to standard terms and conditions, which may be inappropriate for impact bonds.

Potential ‘stumble steps’ on the path to a deal

The allocation of risks and closing the deal will also be different when awarding impact bonds. If the risks are not effectively mitigated, parties may back out. In addition, there are a number of other issues which may arise throughout the procurement process:

- Few high-level impact bond norms/laws. Impact bonds are new tools, and so there are few established norms or formal regulations to guide your thinking. In the short term, learn from others and develop lawyers/procurement specialists; in the longer term, develop norms and regulations.

- Transaction too expensive. The complexity of impact bond contracts results in high transaction costs. This can be mitigated if payers collaborate and build on existing resources.

- Number of service users too low/too high. If participant numbers are low, the provider may be unable to cover costs. Parties must also know the maximum number of service users to build financial models. Contracts may guarantee minimum referrals or decrease prices as referrals increase.

- Active/passive preferences unfulfilled. Different parties have different preferences about how active they want their role in the impact bond to be. It is important that a particular impact bond is configured to reflect the preferences of the other parties you want to attract.

- No contractor protection in case of termination. Providers and investors may worry that they will not be adequately compensated if the contract is terminated early by the outcome payer. Termination clauses set out when and how the contract can be ended, and how payments will be determined.

- Inappropriate payment and monitoring terms. The payment and monitoring requirements of impact bonds differ from those of traditional contracts. Avoid using ‘standard’ terms, or make them clear early to allow providers to build them into their plans.

- Lack of flexibility for changes. Impact bonds are a new way to address complex social issues, and so it’s unlikely that everything will work perfectly from the outset. Contracts should include flexibility for changes to be made, in order to avoid the need for re-procurement.

Introduction

The primary audience for this guide is the outcome payers who wants an active role in the design and performance of the impact bond. It will also be useful to anyone involved in structuring the impact bond. The primary subject of this guide is their outcomes contract.

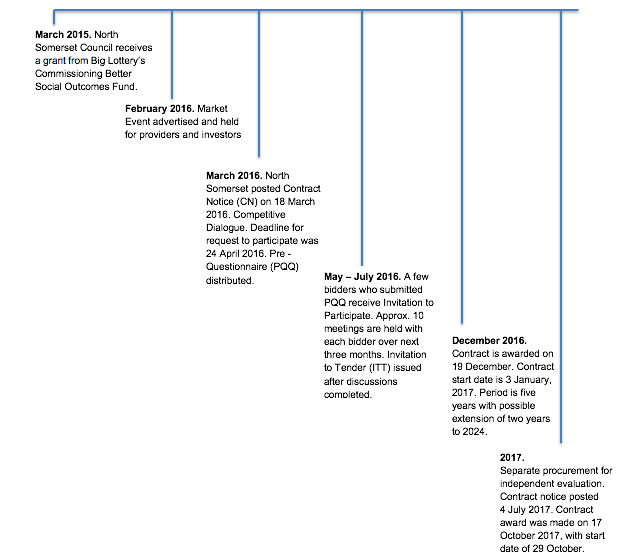

The guide will offer five pointers on procurement and engagement, before describing the structure of an outcomes contract. It will also highlight seven stumble steps to watch when closing the deal. Examples and case profiles are included with associated documents on the GO Lab website.

A note on language: whilst the terminology changes in different countries, this guide will use the term impact bond to refer to social impact bonds, social impact partnerships (a term often used in US legislation) and development impact bond.

What will you learn from this guide?

This guide takes a practical approach to awarding the outcomes contract. It will inform you of different options, the considerations you need to make, as well as offering case studies that will share how others approached this task. More specifically, it will:

- help you think about other comparing different contexts

- help you identify your active vs passive preferences and those of other actors

- give you an understanding around what is different about contracts in impact bonds

- share five pointers for procurement and engagement

- explore the essential elements of an impact bond outcomes contract

- share seven ‘stumble steps’ to watch for when closing the deal

- provide IB case profiles and associated documents

If you are putting together an outcomes contract, we encourage you to also read these resources:

An introduction to impact bonds– If you are new to impact bonds this will help you get to grips with the basic concepts.

Setting and measuring outcomes– This guide will give you an understanding of the outcomes that you need to set and how to measure them.

Pricing outcomes– This guide will help you set up the payment mechanism and set a price for outcomes

Case studies– These will provide information about specific impact bonds. These case studies are more numerous and have a wider focus than the case profiles in this guide.

Throughout this guide we refer to these guides and other resources and examples. We have case profiles in the appendix.

Does this learning apply in your context?

This guide seeks to be helpful to practitioners in many different countries and contexts. This is an ambitious undertaking as there is no single model for the number of parties or their roles, there are lots of different labels for similar things, and context is critical.

For example, in country X there may be good data about the children in the local neighbourhoods and each school, but in country Y, we may not have data on the number of children in the local neighbourhood, their ages, or their attendance at schools.

We encourage the reader to be thoughtful about applying the promising practices highlighted in this guide. What works in one place does not necessarily work in another place. This is particularly important when our subject matter includes highly regulated activities, including provision of social services to vulnerable populations, public procurement, publicly funded projects, data collection, etc.

Beyond regulations, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) has a framework of four “pillars” that may help the reader think about context when translating or generalizing procurement and contracting lessons learned. These four pillars are from the OECD Draft Methodology for Assessing Procurement Systems (MAPS). The following table includes some suggested questions designed to help the reader think about whether this material will apply in the reader’s context.

| OECD MAPS Pillar | Questions to consider before translating or generalising lessons learnt |

|---|---|

| 1. Legal, Regulatory and Policy Framework |

|

| 2. Institutional Framework and Management Capacity |

|

| 3. Procurement Operations and Market Practices |

|

| 4. Accountability, Integrity and Transparency |

|

Does this learning apply to your set of actors?

In addition to contextual variations addressed above, there are variations in the preferences of the parties (stakeholders) in an impact bond. We frame these preferences as varying along a spectrum of passive vs active. Understanding your preferences and the preferences of other parties on this spectrum will help you understand what other actors want from or need in the contract. Understanding your preferences will also help you decide what lessons learnt from other impact bonds are more or less relevant to you. The contractual and practical implications of an active vs. passive investor are discussed more in Chapter 1 and Chapter 4.

Do I have to read everything?

You should only read everything if you work for an outcome payer, such as a government agency or charitable foundation, and you want an active role. Otherwise, the following should help you decide what to skip:

- Chapter 1. What is the deal? This should helpful for most people. It is a general introduction to various configurations of the parties and contracts in an impact bond. High-level policy targets, including the Sustainable Development Goals are briefly addressed. The role of the impact investor is highlighted. The risks to be allocated and/or mitigated are summarised.

- Chapter 2. Five pointers for procurement and engagement. This chapter is less relevant for parties who don’t have access to public money, and/or the impact bond is being designed to scale a specific provider. The focus is on the process of engaging new actors and maintaining flexibility for different solutions for outcomes.

- Chapter 3. What is the outcomes contract structure? This should helpful for most people, but is more technical. The UK social impact bond contract template and the Educate Girls Development impact bond contract are analysed. However, the focus is on the outcome payer’s contract.

- Chapter 4. What ‘stumble steps’ do I need to watch when closing the deal? This should be helpful for people involved in designing and closing the deal. We identify and offer suggestions for avoiding seven potential ‘stumble steps.’

- Chapter 5. Case Profiles. This should helpful for most people. The links to actual documents and templates should be helpful for more technical professionals. We plan to add case profiles as information becomes available.

- UK Annex: Awarding the Public Contract in a Social Impact Bond. This annex is most useful to UK commissioners and public procurement professionals. It may also be useful for other actors in the UK and public procurement professionals in the EU. (Annex coming soon)

What is the deal?

The contracts used in an impact bonds are different from those in other types of contracting such as fee-for-service or grant based agreements. The outcomes payer is not only paying for outcomes, it is also getting a deal to pay after and only if specified outcomes are achieved. This chapter will explore what is different about contracting in impact bonds.

The market and how you engage will be different

Often we think of you – the outcome payer — as entering the market to buy a service. To do so you are likely to have some kind of selection process. If you are a government or entity spending public money there will be public procurement rules designed to secure best value and avoid corruption. As outcome payers you likely have imperfect information – also known as ‘information asymmetry’ – about what services are needed by the beneficiaries, how best to deliver those services, and the cost of delivery.

Another information asymmetry is that you will have less information than the provider about how well the project is proceeding on the ground. So you enter the market wanting to find the best provider about whom you can be confident that they will deliver the service ethically and effectively, and report performance reliably.

All of the above is also true in an impact bond, but if you are paying after and only if outcomes are achieved, this has an effect on the way you engage the market. This is because:

- The provider will need help to cover operating costs and to share some of the risk, which means that they need an investor. (This is the crux of the impact bond.)

- You (the outcome payer) may need to be informed about and/or “warm” the market for a social investment not just for the services.

- You may need to team with other payers to increase the number of beneficiaries to be served and attract more provider and social investment interest and economies of scale.

- Due to the novelty of the process, there may be fewer bidders, only one bidder, and/or the bidder may be a special purpose vehicle.

- To secure the strategic benefits of an impact bond for the contracting authority, some procurement issues have heightened importance.

- In addition to information about the integrity and reliability of the provider, you may need similar information about other parties who may be active, including the investor, intermediary, performance manager, and/or evaluator.

- An active investor or intermediary may hold the most information about the services, their costs, and how performance is going.

In Chapter 2, we offer five pointers for procurement and engagement which address the differences stated above.

It is important to note that the outcome payer is not always the actor driving the market engagement. Active providers, investors, and intermediaries may also enter the market place looking for a buyer to join an IB. This a valid approach, but the focus of this guide is the active payer in the market.

Allocating risks and closing the deal will be different

If you are paying providers after and only if they achieve outcomes, this changes the allocation of risk and way you close the deal.

In all impact bonds there is some transfer of risk from the outcomes payor to the outcomes investor. The most obvious and explicit is the risk that the outcomes are not achieved because the intervention was not successful, so payment is not due. However, other risks also arise in different contexts. In an international context, currency fluctuations are a bigger issue in impact contracts than regular service contracts or grants. Outcome payment, outcome funding, and service delivery may be coming from or happening in different countries with different currencies. The delay between performance and payment increases the risk that fluctuations affect the relative values of the payment, funding, and delivery transactions. Another issue is that the government may change and decide that the contract should not be performed, meaning that the outcomes cannot be achieved even if there has been an investment in start-up or mobilisation.

The extent to which the investor has money on the line is clearly an important practical issue. Therefore, even if they are not a party to the outcomes contract between the payor and the service provider, the impact investor is very motivated to understand this risk and mitigate it. If the risk is too high, that party may balk and walk away, which may cause the deal to collapse.

A potentially bigger issue for the field is the reality that there are no rules governing high-level impact bonds – specific international norms or national laws. In some contexts the novelty and lack of formal rules from above causes implementation problems. This can cause practical difficulties for procurement and legal professionals in compliance-focused environments who do not yet have tried-and-tested templates and compliance practices.

A related practical problem that has emerged is that many organisations’ standard procurement practices and template contract documents do not account for the role of the impact investor. Standard procurement and template contract documents likely have terms that clash with the risk mitigation solutions that may be agreed at a high level between the parties.

The UK government has tried to address these challenges by providing a SIB Template Contract which provides a structure and important terms. However, the critical elements are mostly left blank because they are so dependent upon the specifics of each impact bond. You will, therefore, need to apply the specifics of your SIB into this structure. This will include details on the authorities’ obligations, especially around the qualifying criteria for participants and number of referrals, and your data sharing policy and management information terms, which are important so you can monitor outcome achievement.

The GO Lab has identified seven ‘stumble steps’ to watch that can cause the parties to stumble when trying to close the deal and offers ways to overcome them.

The parties to the deal

The parties involved in impact bonds are outlined in our introduction to impact bonds. In summary, the main players are the outcomes payer, service provider and social investor. The additional stakeholders include evaluators, intermediaries, special purpose vehicles.

The major difference between an impact bond and from other ways of contracting is the active involvement of the investors and/or intermediary. Most basic philanthropic or government contracts focus on two parties: the funder or contracting authority (the outcome payer) and the grantee or contractor (the provider). The government pays and the contractor provides. A grant may be given and the grantee does its best to deliver the services and perform the activities as promised.

However, in an impact bond the provider gets paid after the outcomes are achieved. The investor provides working capital as many provider organisations are charities they may not be able to afford to get paid after they complete the work. Furthermore, payments are made only if outcomes are achieved. Investors take on the risk instead of providers in exchange for a potential return.

An active investor may be a charitable foundation or a specialist team at a financial institution. If not, the investor may want an active intermediary involved. The impact investor and/or intermediary likely understands the intervention and are generally experts managing the risks throughout contract formation and performance.

To maximize the likelihood of success, the investor and/or intermediary will likely be involved in pricing the outcomes, developing the bid, and approving the public contract. They may be involved in managing the data that show whether people are being referred into the treatment and intervention, and whether outcomes are being achieved. Investors may establish a Special Purpose Vehicle (SPV) – a legal entity created solely for the IB. The SPV may be also created for multiple impact bonds.

Investors can be involved in different ways at different times in the development of an impact bond. At one extreme, investors have led projects from the start. At the other, investors have dealt only with providers and had no contact at all with outcome payers. The reality is usually somewhere in between.

Whatever point in time the investor joined and whether or not they are a party to the contract with the outcome payer, the investor will likely play an important and influential role.

Four basic example configurations

Having explained the role of the investor, this section will outline how the parties can configure themselves. There are four basic possibilities:

1. The outcomes contract is between the outcome payer and the provider(s).

Investors can partner with a provider, who is the prime or principal contracting party. This is the simplest and works well when there is just one outcome payer and one provider. This is common in the UK where local government authorities have public (government) contracts with service providers. The service providers are the prime contractors and they have a separate contract with the impact investor. The role of the impact investor is a matter that the outcome payer can explore and weigh up in pre-procurement engagement and through the procurement process, but the outcome payer will not contract directly with the impact investor.

2. The outcomes contract is between the outcomes payer and the investor(s).

Investors can be the prime or principal contractor, and sub-contract to one or more providers. This may be preferable in more complex arrangements where there are multiple outcome payers and/or multiple providers. Investors need to participate in partnership with providers for this approach to work.

3. The outcomes contract is between the outcomes payer and an intermediary, e.g. a special purpose vehicle (SPV).

Instead of the investor being the prime or principal contractor, the advisor or intermediary can play this role. A special purpose vehicle is a legal entity (usually a limited company) that is created solely for a particular financial transaction or to fulfil a specific contractual objective. They are important if there are multiple investors.

4. A multiparty contract referencing additional agreements.

The parties may decide that they all want to be part of the same contract perhaps with additional contracts between individual parties.

|

In practice, there are multiple variations of these three simple models. For example, the Pan-London SIB for Children on the Edge of Care has multiple commissioners and a Special Purpose Vehicle owned by the impact investor. The Educate Girls DIB has a configuration in which five parties are party to a ‘framework’ agreement (i.e. most like figure 4 above). See the Chapter 5 Case Profiles. |

|

Considering a special purpose vehicle (SPV)? Impact investors and/or providers may establish a special purpose vehicle (SPV) - a legal entity (usually a limited company) that is created solely for a financial transaction or to fulfil a specific contractual objective. Consider the advantages and disadvantages to see if they are relevant to you: |

Advantages

|

Disadvantages

|

The parties’ active vs. passive preferences

The parties to any impact bond have different preferences along a spectrum from active to passive. These preferences likely influence the configuration of the impact bond.

Outcome payer

Let’s start with the outcome payer. If you are an active outcome payer, you likely want control over provider and investor performance. For example, in impact bonds in the UK, the payer is most often a local government. They must be very active as they are subject to procurement rules regarding provider and/or investor selection. They often have statutory duties to protect individual beneficiaries receiving the service, and may hold the data on outcomes achieved. In contrast, a private donor who is approached by a fundraiser may be delighted to simply make donations upon the achievement of outcomes. This private donor may be free to donate to their favourite relevant charities without any competitive process and it may be most efficient for them to outsource performance measurement or evaluation to another party.

Investor

Now let’s consider the investor. The active investor wants a direct contractual and financial relationship with the outcome payer. For example, the active investor may set up and own a special purpose vehicle (SPV) to contract with the outcome payer and then have providers as subcontractors with the power to change these providers if they underperform. In contrast, there may be many investors or groups of investors that are looking for socially impactful investment opportunities but have no interest in managing the impact bond and may need the flexibility to enter and leave the impact bond at different points. Most investors in the world beyond impact bonds are passive investors, which is an important factor for some people thinking about scaling up. If you have stock in Google or have a savings account in a Bank, you don’t expect to manage Google or the Bank. You probably do expect regular performance reports though.

The following table provides sample preferences of the various parties, along with example impact bonds to consider.

| Party | Passive | Active | Example IB to Consider |

|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome payer |

|

|

|

| Service provider |

|

|

|

| Investor |

|

|

|

| Advisor / Intermediary |

|

|

|

Risks to be allocated and/or mitigated.

The essence of an impact bond is to transfer risk from the provider to the investor. It is important to note that not all impact bonds allocate all the risks to the investors and not all investors bear the same risk. Some risks may be assumed by the provider. The outcome payer may retain some risk through service payments or start up fees. Grant payments are another way that there is less of a risk transfer.

There are other less obvious risks that arise and may need to be allocated and/or mitigated. The following table is offered to describe the various risks in an IB with some notes. (This risk categories and risks listed are informal and are likely not exhaustive.)

| Risk category | Risk |

Likely risk source |

Likely risk bearer | Mitigation / notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcomes | Outcomes are not achieved by the provider. | Provider | Investor |

This is the crux of the impact bond. i.e. the transfer of this risk from the payer to the provider then to the investor. Not all impact bonds allocate all risks to investors and not all investors bare the same risk. Service payment initiation fees leave some risk with the outcome payer. The provider may not want or be able to transfer all risks to the investor. |

| Outcomes are not achievable at specified rates or levels. | (Whoever designed the outcome) | Investor, (but perhaps every party) | This is more likely to happen where there's poor data on the beneficiaries. The parties can agree to amendment. However, if the contract is a public contract subject to the procurement rules, amendment may not be possible unless this flexibility was included in the original notices and specifications. We suggest building in this flexibility. | |

| Outcomes as defined have no meaningful impact on beneficiaries. | Outcome payer | Beneficiaries, outcome payer | This is a design problem outside the scope of this guide, but it should be considered in the engagement and procurement stages. | |

| Outcomes are achieved but reported as not achieved. | Provider, performance manager/evaluator | Investor | This could be due to a mistake in reporting or evaluation. A process to challenge the data or evaluation findings can be included in the contract. If due to corruption or negligence this would likely lead to dispute. If a corruption issue, conceivably all parties could be at risk for civil or criminal action. The ability of a party to limit liability or to indemnify others may depend on jurisdiction. | |

| Outcomes are not achieved but are reported as achieved. | Provider, performance manager/evaluator | Outcome payer | As above | |

| Service | The service and/or its delivery is harmful to beneficiaries. | Beneficiary | Outcome | Conceivably all parties could be at risk for civil or criminal action. The ability of a party to limit liability or to indemnify others may depend on jurisdiction. |

| Delivery is made impossible due to events outside the parties’ control. | NA | Investor, service provider. | This risk seems readily assignable between the parties. | |

| Service is terminated by the outcome payer. | Outcome payer | Investor, outcome payer (all parties) | Provide a process for changing payers. A termination fee could be included in the contract. If the outcome payer is a government responsible for referring beneficiaries, there could be a guaranteed minimum number of beneficiaries. | |

| Service is terminated by the provider. | Provider | Investor, outcome payer (all parties) | Provide a process for changing providers and/or one of the other parties assuming the role / project assets of the provider. Provide consequences. | |

| Payments & financing | Outcome payer defaults or is delayed on payments. | Provider or intermediary | Investor | Have the outcome payer make payments into an escrow account as services are performed. (It may be a problem for some payers if payments become due years after the services are performed.) |

| Outcome payer makes payments to provider or intermediary who defaults on payment to investor. | Use a configuration in which the investor is paid directly and/or payment is made into an escrow account. | |||

| Currency fluctuation. | (The IB designer to a limited extent) | Investor | The investor receives a return on investment after the achievement of outcomes. The value of the payment currency may change in the interim. We have observed at least one IB where the payment and investment amounts were specified in different currencies |

Five pointers for procurement and engagement

The GO Lab has developed 5 pointers for procurement and engagement aimed at outcome payers. These pointers may be relevant for other parties, especially as the outcome payer may not always be driving the impact bond development.

1. Impact bond with friends

Consider collaboration with other potential outcome payors. Join a team that already exists. Re-use existing SIB and DIB templates. If you are a government agency, consider co-contracting.

Every local place and beneficiary is unique, but many social problems extend beyond local boundaries. Increasing the number of beneficiaries can reduce the per-beneficiary costs and attract more potential providers and impact investors. The transaction costs involved in an IB are significant and could be shared by outcome payers. The outcome payers in some early impact bonds are deliberately sharing their experiences and documents for use by others in an attempt to reduce future transaction costs and scale the market.

If you are a government agency, you might want to consider co-contracting (sometimes known as co-commissioning) with other regions as part of procurement preparations. One benefit of co-contracting is that risks around referral rates can be mitigated and shared by the outcome payers.

| Five London borough councils have come together to co-commission the Pan-London SIB for Children on the Edge of Care. The co-commissioners are the London Boroughs of Bexley, Merton, Newham, Sutton, and Tower Hamlets. (A sixth borough council, Barking and Dagenham, joined after the award of the public contract.) The cocommissioning relationship is formalised in a 2017 “Inter-Borough Partnership Agreement.” See Chapter 5 Case Profiles for more information. |

|

DIFID, USAID, and an anonymous donor are collaborating as outcome payers in the Village Enterprise DIB being delivered in Kenya and Uganda. Village Enterprise is a micro-enterprise graduation programme that aims to increase the incomes of individuals living on incomes of less than £1.90/day through training, seed grant funding, and mentoring. See Chapter 5 Case Profiles for more information. |

2. Widen your market engagement

Engage with a broad range of investors and providers. Use your convening power to create new potential matches.

The impact bond marketplace is small compared to overall spending on social services and development. If outcome payers wish to leverage impact mechanisms, more providers will need access to investors.

One solution identified is for outcome payers to host ‘market-warming’ events. Like traditional events, providers can be presented with requirements and asked for solutions. Potential investors should also be invited and encouraged to meet with providers.

Government agencies that would be outcome payers should utilise public procurement mechanisms to publish their interest in paying for outcomes via an outcomes contract. Government agencies subject to the EU Procurement Directive can utilise the Prior Information Notice (PIN) notice process for this purpose and should clearly state that they are in the market for providers and investors.

Additionally, this suggestion has transparency benefits. Clear notices will help develop your market in the long term by helping other providers understand that you are procuring impact bonds, and buying with ‘after and only if’ terms so they can prepare for such a deal in the future.

3. Be flexible about how outcomes are achieved

Your specifications should focus on the social outcomes rather than on how they are to be achieved – except when it comes to minimum service standards.Consider linking outcomes to the Sustainable Development Goals. (Note we are not suggesting flexible outcomes. Nor are we saying the proposals should be vague.)

In your communications to the market, be as flexible as possible regarding the inputs and activities required to achieve the outcomes, allowing the provider to propose how they will achieve them. There are benefits to this flexibility. During market engagement and procurement, you may receive more interest and more alternative solutions or innovation. During contract performance, all parties may be more responsive to lessons learnt if the service delivery can be adjusted.

This flexibility around the “how” is sometimes called ‘black box’ procurement. The concept of a ‘black box’ is that the outcome payer does not focus on the inner workings of the intervention (the box) they just see inputs and outputs. What the outcome payer includes in the specification of the work they are procuring and how they assess the proposals received is a different question.

In a ‘grey box’ scenario there may be a mix of flexibility alongside minimum service standards.

In many situations, minimum services standards are important and are rightfully inalienable. Many of the beneficiaries are vulnerable people such as children in care or in difficult family situations. As an extreme example from the international development context, there have been serious ethical issues around forced and/or highly incentivised sterilisation programme in India as a means to control the population. In many projects, data is required to be collected about beneficiaries and these data may be subject to data protection and other rules. Clearly, specifications should include minimum service standards necessary to protect beneficiaries, while allowing as much flexibility as possible regarding how to achieve the outcomes.

For government agencies subject to EU or similar procurement rules, flexibility around the “how” may be especially important and helpful. If you are too detailed about the inputs and activities in your notices and invitation to tender documents, then making changes may require a contract cancellation and re-procurement. Even if the contract provides for changes, changes cannot be beyond the scope of published notices. As fun as procurement is for everyone, nobody wants contract cancellation and re-procurement for the same outcomes!

A focus on outcomes rather than activities may present an opportunity to advance the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development adopted by all United Nations Member States in 2015 and the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).The 17 Sustainable Development Goals are defined in a list of 169 SDG Targets (see definitions here) and progress towards these being tracked by 232 unique Indicators. (See SDG Tracker here.) Many outcome payers have aligned their mission and spending priorities towards these goals. Flexibility around the outcome in an impact bond allows the outcome payer to spend resources towards a goal while seeking solutions from providers that are specific to local communities.

Working with partners to specify outcomes during engagement and procurement is likely an effective way to operationalise SDGs (or other policy goals) and collect performance data. As noted in Chapter 1, buyers likely have imperfect information about what services are needed by the benefices, how best to deliver those services, and the cost of delivery.

Note that this pointer is not about flexibility on the outcomes or beneficiaries. Outcomes and beneficiaries need clear definitions. See our technical guide on Setting and measuring outcomes guide for more information.

Also note that this pointer does not suggest that proposals should be vague. The buyer should understand the solution. An active outcomes payer will require detailed information from potential providers during their assessment of solutions, including information on risk management, costs and operating model, mobilisation and implementation. (See example from North Somerset in the call out box below.)

|

In December 2012, Birmingham County Council advertised a contract titled, “Children in Care Services - Payment by Results.” The contract sought to reduce the number of children in residential care because of evidence that foster placement can be better for children. Foster care is also less expensive than residential care for the council. The advertisement stated, “The Council has chosen not to prescribe the services to be deployed, the provider will identify the most appropriate service offer through access to the needs profile, current service take up of the cohorts and the application of their expertise.” The Specifications included a high-level outcome: “The improvement of outcomes of the young people within the defined Cohorts of Children in Care, by ensuring that young people remain or are returned home, where appropriate, or placed in family placements. Additional outcomes were also provided, but were very flexible about how the outcomes could be achieved. The specification stated: “Due to the nature of this procurement i.e. service interventions are not being prescribed by the Council at the outset this service specification should be regarded as being subject of dialogue through the procurement process. It sets out the principles of what we wish to achieve and will be modified as the procurement progresses.” (Cover page of the specifications.) The Specifications also stated that, “The majority of inputs will be determined by the service proposed by Tenderers and will be developed as the procurement progresses.” See Chapter 5 Case Profiles for another example in North Somerset Council's “Turning the Tide” SIB. |

|

This pointer does not mean that proposals should be vague. Example from North Somerset. In North Somerset Council's “Turning the Tide” SIB, the Commissioner was initially flexible about how the outcomes were to be achieved and invited a wide range of solutions. Nonetheless, in the procurement process, the Commissioner sought detailed information about potential providers’ solutions, including costs and operating model, mobilisation and implementation. The proposals invited were asked to respond to the evaluation criteria in the table below: See Chapter 5 Case Profiles for information on North Somerset Council’s SIB. |

| Evaluation Area | Criteria | Weighting |

|---|---|---|

| Financial |

Cost of delivery to the council:

|

25% |

Contractual Delivery Model:

|

15% | |

| Quality |

Quality of intervention:

|

25% |

Quality of people delivering the intervention:

|

15% | |

Quality Assurance/Governance:

|

10% | |

| Implementation |

Implementation and mobilisation:

|

10% |

4. Secure the strategic benefits

Secure the strategic benefits of an impact bond with an evaluation, transfer of data and data capacity, and transparency. That ‘black box’ or ‘grey box’ should eventually be opened for learning.

The potential benefits (and limitations) of impact bonds are outlined in the introduction to impact bonds. The outcomes contract can play a critical role in securing these benefits. If this is not done well, too much knowledge and power may be transferred to a small amount of investors. Learning or capacity that has been developed may be lost when the contract ends. To secure these strategic benefits, the GO Lab encourages outcomes payers to think about the following:

(a) Evaluations

Many impact bonds require an evaluation as part of the payment mechanism, but others make payment on the basis of administrative data. In both scenarios an evaluation may be helpful to understand what happened and how it happened. There are many benefits to conducting an evaluation, as highlighted in the GO Lab’s evaluating outcomes-based contracts. Delivery of an evaluation or participation in an evaluation project can be specified in the contract.

(b) Measures, measurement, and data

Recall that the investor or provider will be doing a lot of performance measurement to manage progress towards the outcomes. The outcomes payer should consider how much of these performance data they need to oversee performance and include it in the outcomes contract in the form of a Data Sharing Agreement. The Data Sharing Agreement should include delivery of data in a reusable format with clear data definitions. The Data Sharing Agreement and/or reporting terms should describe regular points in time when data are shared and their meaning explained.

Some impact bonds are implemented in data desserts. There may be little or no information about the beneficiaries or the activities in the absence of the intervention. This means that measuring the achievement of outcomes is a significant undertaking in itself. Resources will be spent on developing a process to collect data. The outcome payer should think about whether this process and associated tools is an asset that should be transferred to the public agency or other party at the end of contract. Training and/or transfer of intellectual property may be required for the transferee to maintain the data collection process. If so, this should be part of the original specifications and the contract so the provider can address this issue in the proposal.

If you are a government agency, data access and any transfer of the data collection process should be included in notices, pre-qualification materials, full tenders, and the contract. Consider including this issue in the tender evaluation/award criteria scoring as well.

(c) Transparency

Transparency during contracting and performance is important. The impact bond mechanism is relatively new, so more people understanding how it works may help scale the market and reduce transaction costs. Open data on spending can also help outcome payers see where others are spending and on who or what, so they can co-coordinate their efforts in a smarter way.

In the development context, there is an International Aid Transparency Initiative (IATI) which provides an open data standard about how aid money is spent. An increasing number of governments are using the Open Contracting Data Standard (OCDS) to make their public procurement data and documents publicly available. (IATI and OCDS are essentially a public list of data definitions with a process for sharing the data.)

The outcomes contract should explicitly state that the contract itself may be shared publicly, but perhaps with the other parties having the opportunity to redact confidential information. Where there is to be an evaluation, the outcomes contract should provide for the public release of the evaluation. The outcomes contract could also allow periodic transparency reports to be released describing performance. The contract could require that these reports be available in IATI and/or OCDS standards as may be appropriate.

A potentially thorny issue relates to pricing outcomes. It is the GO Lab’s opinion that prices paid for outcomes should be open data, especially if payment is made with public funds. We also feel that data about prices paid should be accompanied by appropriate and sufficient explanation so people can understand the prices and their context.

5. Engage with impact bond beneficiaries and their representatives

Don’t lose sight of the beneficiaries. Ensure the service has been co-designed by beneficiaries or their representatives. Consider how beneficiaries should be involved in service delivery, feedback, and monitoring of outcomes.

Most of this guide focuses on the outcome payer, the provider, and the investor. However, we cannot lose sight of the beneficiary. All high-quality providers are likely to have high levels of engagement with beneficiaries. Nonetheless, outcome payers may want to consider how they can include beneficiaries more explicitly in impact bond development and implementation. This could be achieved by running a consultation alongside a market warming initiative and/or asking the bidders to describe the ways in which beneficiaries have been engaged in the design of the intervention and are to be engaged during performance.

If impact bonds are to scale up and have greater impact, the issue of consultation and engagement will likely grow in importance in the future.

What is the outcomes contract structure?

In this chapter we outline the UK Government’s SIB Template Contract and additional elements for an international development context. We compare the UK SIB Template Contract to the Educate Girls “Framework” (DIB) Contract. (Educate Girls case profile coming soon)

Obviously, one of these instruments is a template and one is a specific executed contract. One problem we have is that UK SIB parties have been slow to share their executed contracts. Nonetheless, the similarities and differences are instructive.

Many of the core terms are the same and, in the Educate Girls contract, England and Wales is the governing jurisdiction. Significant differences include the way multiple parties are handled and the presence of an evaluation. We suggest parties start with an impact bond contract as a starting point rather than use standard service contract terms and conditions. In the UK, we have observed problems with local governments trying to attach standard terms and conditions to the impact bond. (These problems are addressed in the next Chapter.)

UK SIB Template Contract

The underlying aims of the UK SIB Template Contract are:

- “Providing a balanced document that should be broadly acceptable to commissioners, service providers and investors.

- Striking a balance between simplicity, materiality and proportionality.

- Providing a clear position on substantive issues (to limit time spent negotiating those) but leaving it open for genuine project specifics or issues of particular concern to commissioners, service providers and investors (if any) to be added in.”

(Drafting Principles in the SIB Template Contract Guidance Document.)

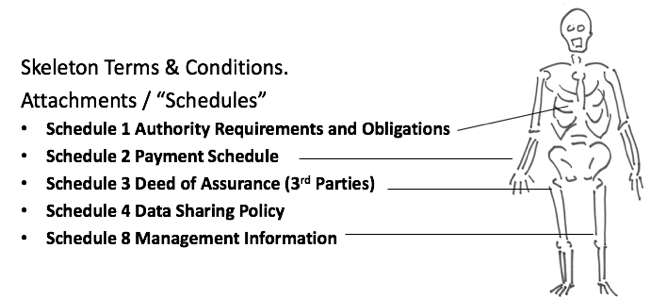

The Template provides contract terms that reference key attachments or “schedules,” which are appendices for essential elements of the impact bond. If the Template is the bones of the SIB, the schedules are the organs. The SIB Template schedules are mostly blank and need to be completed according to the needs of the specific impact bond.

The blank gaps in the Template schedules are somewhat necessary due to the variation between different SIB projects. Nonetheless, the GO Lab believes templates or examples from existing SIBs would be helpful. As noted above, UK SIB parties have been slow to share their executed contracts. If parties to existing SIB parties shared more of their contractual documents, this would likely reduce the transaction costs for other local authorities. Parties to new SIBs could set expectations that contract documents will be redacted and shared. (This was one of the issues made in the fifth engagement / procurement pointer “Secure the strategic objectives.” See Chapter 2.)

Parties in the UK SIB template contract

The UK SIB template contract is designed for two parties: a public (government) contracting authority and a prime contractor. A Deed of Assurance (Schedule 3) is provided as the mechanism by which the contracting authority may want to tie-in a subcontractor. (See Chapter 1 for discussion of SIB structures.) For example, if your direct contractor is an SPV or investor, you may want some control over changes to the subcontractor providers. Alternatively, if your prime contractor is a provider, you may want some control over any changes to a subcontractor who is providing performance monitoring data. The Deed of Assurance includes Step-In Rights in Favour of the Authority (i.e. outcome payer) which can result in the payer becoming the direct client of the subcontractor. (See Schedule 3, Section 7.)

Outcomes specification and payment terms in the UK SIB Template

Among the most essential elements of a SIB are the outcomes specification and the payment terms. The SIB Template Contract addresses these elements as Schedule 1 Authority Requirements and Obligations, which includes the outcomes specification, and Schedule 2 Payment Schedule.

The content of these schedules will be a combination of the specification, the bid, and the negotiations. The GO Lab technical guide on Setting and measuring outcomes and Pricing outcomes can be consulted during this process. The main point for procurement and legal professionals here is to avoid additional requirements about inputs or implementation. Earlier in this guide, the second procurement pointer highlights that transparency notices and specifications should be specific on the outcomes to be achieved, but flexible on how the outcomes should be achieved. (See Chapter 4.) The same reasoning exists here. During contract performance, all parties may be more responsive to lessons learnt if the service delivery can be adjusted without the need for a contract amendment or re-procurement.

Performance Data and (no) Evaluation Data in the UK SIB Template

The SIB Contract Template provides a Schedule 4 Data Sharing Policy andSchedule 8 Management Information, but these schedules are also both blank slates. Earlier in this guide, the fifth procurement pointer highlights the importance of having a good data sharing policy to secure the SIB’s strategic objectives. Later in this guide, the issue comes up again as a fourth hurdle to closing the deal in the context of inappropriate monitoring terms.

Most recent SIBs in the UK do not use impact evaluations as part of the payment mechanism. Payments are often tied to relatively short term outcomes that are reported using administrative data collected by the provider and/or the government authority that is the outcome authority. When they happen, evaluations of UK SIBs tend to be been separately commissioned outside of the outcomes payment mechanism.

Educate Girls DIB Framework Contract

The Educate Girls DIB included five parties from four different countries. None of these parties was a public (government) agency nor were they spending public funds.

The core agreement between the parties was referred to as the ‘framework’ contract. This framework contract is similar to the UK SIB Template Contract in its skeleton terms. However, rather than describe the outcomes and payment terms in attachments, the Educate Girls DIB had three additional “connected” but separate agreements between the various parties:

- Outcomes Payment Agreement between the outcomes payer (a private foundation) and grantor (Investor)

- Grant and Services Agreement between the grantor (investor) and the provider

- Evaluation Agreement between the outcomes payer and the evaluator.

The outcomes and payments are described in these other agreements. The attachments (schedules) to the framework include the following:

- Schedule 1: Randomisation Tables (for the evaluation).

- Schedule 2: Conditions Precedent.

- Schedule 3: Performance Management Framework.

- Schedule 4. Child Protection Policy.

Parties in the Educate Girls DIB Framework Contract

While the UK SIB Template contract is designed for two parties – the government contracting authority and a prime contractor, who would likely be the provider or a special purpose vehicle – the Educate Girls contract is between the outcomes payer, the grantor (investor), provider, and the evaluator. There is no need for a Deed of Assurance in this scenario because all the essential parties are prime / direct contractors.

Outcomes and Payments in the Educate Girls DIB Framework Contract

The outcomes description and payment terms in the Educate Girls DIB are not defined in the framework contract or its attachments. These are found in ‘connected’ but separate contracts between the parties described above.

Other clauses in the UK SIB Template Contract and the Educate Girls DIB Framework Contract

The following table compares the UK SIB Template Contract and the Educate Girls DIB Framework Contract as it relates to many standard contract issues. Note that this table does not cover the larger contract structure issues related to parties, outcomes, and payments addressed above.

| Clause Subject Matter | UK SIB Template Contract Clause # | Girls Contract Clause # | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Definitions and interpretation | 1 | 1 | |

| Statement of shared aims | 2 | ||

| Commencement and duration | 3 | 2 | |

| Mobilisation | 4 | 3 | |

| Deed of assurance | 5 | The Deed of Assurance is for binding subcontractors. The Educate Girls Framework has five (prime) parties to the contract. | |

| Contractor warranties and representations | 6 | 4 | |

| Conflicts of interest | 7 | 5 | |

| General assistance and cooperation | 8 | 6 | |

| The services | 9 | ||

| Authority obligations | 10 | ||

| Authorised representatives | 11 | ||

| Review, monitoring and information/review and access | 12 | 9 | |

| Payment provisions | 13 | ||

| Change procedure | 14 | ||

| Data protection | 15 | The Educate Girls contract predates the UK’s Data Protection Act 2018 and does not say a lot about data protection. There are relevant provisions in Clause 20 CONFIDENTIALITY, including a reference to the jurisdiction where data was collected. | |

| Freedom of information | 16 | The Educate Girls parties are not subject to the FOI Act and the contract does not include provisions similar to FOI. | |

| Confidentiality | 17 | 20 | The UK SIB Template Contract provisions are more detailed and restrictive. The Educate Girls contract states that “aggregated anonymised data may be made public.” |

| Publicity | 18 | 19 | |

| Intellectual property | 19 | 17 | The UK SIB Template Contract secures a license to the payer to use any intellectual property developed by the provider for the purposes of the services. The Educate Girls contract does not include such a license. |

| Indemnities | 20 | For the Educate Girls DIB, indemnities and insurance are addressed in the Grant and Services Agreement between the Grantor (Investor) and the Service Provider. | |

| Insurance | 21 | For the Educate Girls DIB, indemnities and insurance are addressed in the Grant and Services Agreement between the Grantor (Investor) and the Service Provider. | |

| Force majeure | 22 | 11 | |

| Bribery, corruption, gifts and fraud | 23 | ||

| Default/termination of the appointment of provider | 24 | 13 | |

| Continuing obligations on termination | 25 | 14 | |

| Transition to another contractor | 26 | The Educate Girls contract did not provide for transition to another service provider. | |

| Transfer of undertakings /protection of employment (TUPE) and employees | 27 | This is about UK specific regulations designed to protect employees transferred to another business. | |

| Pensions | 28 | Concerns transfer of employee pensions. | |

| Dispute resolution procedure | 29 | 15 | The timeline in the UK SIB Contract Template is shorter / moves more quickly. The Educate Girls provisions include Evaluation Dispute Resolution procedures. |

| Assignment and subcontracting | 30 | 16 | |

| Change in ownership | 31 | ||

| Entire agreement | 32 | ||

| No partnership or agency | 33 | 21 | |

| No waiver | 34 | 22.2 | |

| Severance/partial invalidity | 35 | 22.1 | |

| Notices | 36 | 23 | |

| Contracts (rights of third parties) Act 1999 | 37 | 22.3 | |

| Law and jurisdiction | 38 | 24 | The Educate Girls contract specifies the laws of England and Wales as governing. (In Clause 20. CONFIDENTIALITY there is a reference to data protection and confidentiality requirements in the jurisdiction where the data was collected.) |

| Integrity of the project | 7 | The Educate Girls is subject matter specific, whereas the UK SIB Template Contract is general. Clauses 7 and 8 reflect the concern for integrity and minimum service standards that are especially in a development context. | |

| Child protection | 8 | The Educate Girls is subject matter specific, whereas the UK SIB Template Contract is general. Clauses 7 and 8 reflect the concern for integrity and minimum service standards that are especially in a development context. | |

| Evaluation | 10 | The UK SIB Template Contract does not have an evaluation clause. Most UK SIBs do not use an independent evaluation linked to the payment mechanism. | |

| Transaction expenses | 18 |

What ‘stumble steps’ do I need to watch when closing the deal?

In a medieval castle a ‘stumble step’ was designed to be a different height than the previous steps so invaders would trip up and fall when climbing the stairs. The GO Lab has observed 7 potential ‘stumble steps’ which may cause your deal to fall. We also offer suggestions on how to avoid tripping on these when closing the deal. (We are not commenting here on whether these are inherent in the design.) In the previous chapters we identified the structure of the contract. In this chapter we are focused on practical issues around getting the parties to sign the contract and launch the project. In addition to these specifics solutions, some general considerations will help mitigate these potential hurdles:

- Involve your lawyers and procurement professionals early in the process.

- Start with the UK SIB Template Contract or an example suited to your context.

- Consider using “conditions precedent,” in which a list of issues must be resolved during the start-up period before performance can begin.

- Do not over go over-board with complexity and keep the contract as light and simple as possible.

|

Using “conditions precedent.” Example from the Pan-London SIB. One promising practice comes from an interesting element of the Pan-London SIB contract mentioned earlier: the use of “conditions precedent.” The contract was awarded on September 1, 2017, but performance could not begin unless a number of issues were resolved during a six-month initiation phase. Issues to be resolved after award and before performance included:

See Chapter 5 Case Profiles for more information on these SIBs. |

1. There are few high-level impact bond norms or laws.

Suggestions: Acknowledge that we are in emerging and evolving space with few international norms or national laws. Consider the regulatory and policy environment and other contextual factors. Engage the lawyers and procurement early. Focus on policy documents and the emerging best practices in published documents.

Impact bonds are an innovation that is emerging in social service delivery. There is no reference to impact bonds in long-standing high-level international tools such as the United Nations Model Procurement Law or the international commercial terms published by the International Chamber of Commerce (ICC). Nor is there any reference to impact bonds in the European Procurement Directives (2014). Too our knowledge, impact bonds have not been tested in courts.

In the country with the most impact bonds – the UK – there are no impact bond-specific statutes or regulations. The UK’s central government policy in favour of impact bonds has been driven not by legislation or regulation, but through funding and softer policy tools. The outcomes funds run by central government to help support to local government-run impact bonds are quite flexible. In contrast, the US Social Impact Partnerships to Pay for Results Act (SIPPRA) is a federal law that is quite prescriptive about, for example, the type of evaluation required in the impact bonds funds it will support.

The lack of express legislative or regulatory guidance may make it more difficult to get impact bonds off the ground. The point here is not that legislation or regulations prohibit IBs. On the contrary, for example, the EU Procurement Directive has a lot of flexibility to be leveraged. (See UK Annex.) The point is that while many procurement and legal professionals excel at innovation and the art of procurement and lawyering, others are more comfortable (or are forced to operate) in an environment of compliance that is highly regulated.

Acknowledging these realties, may help keep the gears on an impact bond moving. Identifying and engaging legal and procurement professionals who are able to operate in this environment is important. Engaging them with enough time to analyse legal risks early in the process is also important.

In the immediate term, sharing lessons learned and resources is especially important in the absence of high-level norms, legislation, or regulations around outcomes-based contracting. Resources such as the UK SIB Template Contract and, for example, the Educate Girls framework contract become especially valuable. (Of course, the reason for this guide is to promote access to lessons learned and these resources.) A medium term solution is to support capacity development of procurement and legal professionals. A longer term solution is perhaps to develop high-level norms, legislation, or regulations around outcomes-based contracting.

2. The transaction seems too expensive for us right now.

Suggestions: Engage additional outcome payers. Re-purpose and then share resources. Join or create flexible, expandable contract mechanisms.

A common criticism of impact bonds is that they are complex and expensive to launch – the transaction cost is too high for a specific party at a specific time. Whether the impact bond costs are worth the promised net benefit to society is still being explored, but is not the point here.

Whatever the overall costs and benefits to society, a practical question is who bears the costs when launching the impact bond. A lot of the issues that could otherwise be spread across the life of the contract – or just ignored – now have to be handled up front at contract inception. The deal can die as the upfront transaction costs to the payer or other parties become clear.

Sharing these costs is the first and most obvious potential solution. Efforts to spread these costs include accessing development grants, pro-bono legal services, and/or accessing outcomes funds / trusts. The parties to an individual impact bond may have come together specifically to access such mechanisms. If you have not done so already, consider expanding the collaboration to include other parties interested in helping to fund evaluation, learning, and capacity development.

Most of the impact bonds launched in the UK involve local government outcome payers who are incentivised by grants and top-up funds from central government funds / trusts, such as the Life Chances Fund. In most cases, the costs for evaluation and learning from the projects have been borne centrally rather than on the individual project. In the development context, the potential for capacity development around data collection and data use is a benefit that different funders have been trying to encourage through different mechanisms. If your impact bond promises learning or capacity development outcomes that are valuable to other funders, you should consider engaging those funders.

A second solution, also obvious in theory, is to re-use and then share resources and tools. The previous point was to get help funding your learning. This point is to use the learning of others. The UK SIB Contract Template will be a good starting point for many potential SIBs. However, UK SIB parties have been reluctant to share their actual contracts and associated documents, making this obvious solution difficult in practice. DIB parties seem more open to sharing. The resources available associated with guidance on the GO Lab website are designed to assist parties reduce their transaction costs. We encourage parties to re-use these resources and share their own resources. (See also the 4th pointer for procurement and engagement: Secure the Strategic Benefits.)

A third, more radical and potentially impactful solution, is to join (or set-up) impact bonds that are expandable. A few contracts have been established to allow new providers and beneficiaries to be added into the contract. The logic behind this suggestion is similar to the logic behind the multiple award schedules in the US context. The idea here is that the individual actors can on-ramp or off-ramp and the transaction costs for individual orders is reduced because some of the terms are fixed at the expandable contract level. The example of the Pan London SIB is instructive and the Interagency Partnership Agreement used in the Pan London SIB may be an especially helpful resource here. (See below and in the case profile in Chapter 5. See also the 1st Pointer for Procurement and Engagement: IB with Friends.)

(The point here is that the transaction costs may be unbearable by one actor at the start of the process. However, if the overall costs are higher than the net benefits to society in any timeframe, no amount of sharing or spreading the costs should be justifiable. If there is no social net benefit, we should all be prepared to say that these steps are not to be climbed. For more information on cost benefit analysis of IBs see the pricing outcomes guide)

|

In practice, there are multiple variations of these three simple models. For example, the Pan-London SIB for Children on the Edge of Care has multiple commissioners and a Special Purpose Vehicle owned by the impact investor. The Educate Girls DIB has a configuration in which five parties are party to a ‘framework’ agreement (i.e. most like figure 4 above). See the Chapter 5 Case Profiles. |

3. The number of beneficiaries is too low or too high.

Suggestions: Consider expanding your focus to include more beneficiaries. Consider guaranteeing a minimum number of beneficiaries / referrals into the service. Consider roll-over options.

There are two overlapping issues here – the second of which is more relevant. The first issue is that the scale of the impact bond is important to attract parties and ensure the anticipated benefits to society outweigh the costs. The issue of scale may be addressed by collaborating with more partners and perhaps creating expandable contracts to increase the number of beneficiaries. (See previous step.)

The second is a very practical issue about the extent to which the parties will commit to a specific scale in the contract. This issue is particularly important when the payer is a small local government focused on a group of local beneficiaries for whom they are responsible. In these cases, the outcome payer may be responsible for referring individual beneficiaries into the service. The parties will therefore be very focused on the number and characteristics of people to be referred because this affects the minimum and maximum outcomes that may be payable.

The same issue may arise in the development context where the actual number of beneficiaries and their relevant characteristics may be fuzzy or inaccurate due to data quality issues. For example, if there are no good data on the number of school-aged children in a region, one cannot be certain how many of those children can be enrolled in school.

The problem is that if there are few beneficiaries, the contractor may not be able to cover their mobilisation or set-up costs. The parties may need to consider whether it is appropriate to guarantee a minimum number of eligible referrals. This effectively involves committing to a guaranteed payment for that minimum number whether or not the referrals are actually made – i.e. “meet the minimum or pay anyway.” The same end could also be achieved by prescribing a termination amount, as described below.

At the other end of the scale, the maximum number of beneficiaries and/or the maximum outcome payments will need to be set. This information is important for parties to build their financial models, so maximums should be addressed as early in the process as possible.

There may be some culture shock around the guaranteed minimum referrals or termination fee. The issue is likely more controversial where the payer is a local government and there is a small number of potential beneficiaries because the margin between minimums and maximums may be very narrow. If the margin is too narrow, the local government may too easily fall below the minimum.

One alternative or additional approach is to have different pricing for different ranges or numbers of referrals. The first group of beneficiaries would be higher prices with higher numbers at lower prices. This may give the authority extra value for money where the programme was scaled up, but could also be used to protect the contractor in circumstances where the level of referrals is lower than expected.

In all cases it is important to consider and describe a "qualified" referral or beneficiary, paying attention to the risk of the contractor undertaking creaming (only taking easy referrals) and parking (diverting attention from more difficult cases after they have been referred). Criteria for a qualified referral and/or supporting data should be included in the procurement documents.

Minimal and maximum beneficiary numbers are important information for parties to build their business and financial models – including both the pricing structure and the investment structure. The UK SIB Contract Template does not provide clauses on the minimum or the maximum number of people that will be served, but this can be included in Schedule 1 Authority Requirements and Obligations and/or Schedule 2 Payment Schedule. There is more information on this topic in the guide to setting and measuring outcomes.

4. Our active or passive preferences are unfulfilled

Suggestions: Identify your preferences and those of other parties on a spectrum of active vs. passive. Select an impact bond configuration that is likely to suits the preferences of the other parties you want to attract. Anticipate other parties’ likely expectations and performance needs.

As noted the in the introduction and expanded upon in Chapter 1, your preferences and those of other actors likely vary along a spectrum of active vs. passive. We have observed that active outcomes payers, such as government agencies, can be surprised by the high profile role of active investors or intermediaries. (Governments are more used to contracting with providers and the active role of the investor may cause tensions that need to be resolved.)

We are not suggesting that one preference is better than the other. It is too early to suggest that a specific combination is more or less likely to succeed. However, the table offered in Chapter 1 will may help you either set up an IB to attract the type of partner(s) or anticipate what other partners will need.

For example, if you know that you want to attract active investors or are already working with an active investor, you should probably set up or anticipate that the investor may want a direct contractual and financial relationship with the outcome payer – perhaps as a party to the outcomes contract. On the other hand, if you want to attract a lot of different investors to the project, including passive investors, you likely need a configuration that allows investors to enter and exit the IB with minimal disruption to the outcomes contract.

5. No contractor protection in case of termination

Suggestion(s): Use the termination clauses in the UK SIB Template Contract, which include voluntary termination after 24 months with payment to the contractor of an ‘Authority Default Termination Sum.’ If not using these terms, the authority should make cancellation terms explicit as early as possible.

In order to develop its financial model, the contractor (provider, investor, and/or intermediary) needs to understand what will be paid if the payer makes a voluntary termination or defaults. This is because the contractor may not have had the chance to achieve enough outcomes at the point of termination to cover their costs up to that point and the termination will deny them the chance to achieve more outcomes in the future and recoup their upfront costs.

One way to work out how much to pay a contractor on termination is to include a mechanism to estimate what outcome payments would have been made if the contract had been continued. On the one hand, the IB is premised on the possibility that some or all of the potential outcomes may not be achieved. On the other hand, the contractor has signed up for the opportunity to achieve all the outcomes and receive all potential outcome payments (or at least enough to get back their up-front investment).

The UK SIB Template Contract strikes a balance by providing a voluntary termination mechanism with an "Authority Default Termination Sum," calculated on a gross "Minimum Expected Outcomes" amount to be specified. However, the voluntary termination mechanism allows termination after 18 months of performance following services commencement and requires at least 6 months' notice (in other words, voluntary termination is not possible within 24 months under the template). This might give the contractor a chance to achieve some outcomes and give an indication of likely level of performance for the rest of the contract – but whether this is long enough will depend entirely on the payment terms of the particular contract.

Like any contract, the UK SIB Template Contract also provides a mechanism for contractor termination under certain defined circumstances (for example, bribery, corruption, gifts, and fraud), or following a performance improvement plan.

6. Inappropriate payment and monitoring terms

Suggestions: Consider using the UK Government’s SIB contract template and focus on how the outcome achievement is to be verified. Avoid adding ‘standard’ terms and conditions that create new risks of non-payment for outcomes. Alternatively, allow actors to address and/or price-in your standard payment terms by including them in preliminary market consultations, notices and/or specifications.

The UK SIB Template Contract has payment provisions which wrap around and complement Schedule 2 Payment Schedule. The clauses anticipate both Service Payments and Outcome Payments. Fundamental to a SIB is that Outcome Payments are made after and only if the specified outcomes are achieved. The Schedule 2 Payment Schedule is blank because there are different approaches to specifying the outcomes, defining the prices to be paid for outcomes, and determining that a specified outcome has been achieved (i.e. what triggers payment). The reader may find helpful the setting and measuring outcomes guide.

In the typical impact bond, the provider does not submit an invoice to the outcome payer. The provider likely does not control the data about whether outcomes have been achieved. Many ‘standard’ terms for traditional fee-for-service contracts include invoking, inspection, acceptance, and payment provisions are not appropriate for outcome payments. Typical monitoring requirements based on inputs or specific activities may also be inappropriate.

Performance data may be controlled by a performance manager, evaluator, or the even the outcome payer if the payer is a government agency with responsibility for beneficiaries. All parties will therefore be interested in accessing these data outcome has been achieved, then there needs to be a process around mutual access and validation of the data.

The UK SIB Template Contract clauses provide service fee payments on a monthly basis and Outcome Payments within twenty days of invoicing. Authorities may want to consider whether twenty days is sufficient time to process the Outcome Payment in circumstances where the trigger may rely on a third-party evaluation or not be a fixed date in time. The UK SIB Template Contract seeks to strike a balance with clauses on monitoring and information and audits that complement Schedule 8 Management Information and Schedule 2 Data Sharing Policy. The clauses allow the outcome payer to inspect the contractor three times a year or more times if required by statutory duty or under a performance improvement plan. Additionally, the authority can audit the contractor twice a year. Adding further monitoring requirements may increase contractor costs or constrain the contractor’s flexibility during delivery.