Impact bonds

This guide will explore what impact bonds are, the evidence to date and how they work in practice in different countries around the world.

Overview

3 minute read

Impact bonds (IBs) are outcomes-based contracts. They use private funding from investors to cover the upfront capital required for a provider to set up and deliver a service. The service is designed to achieve measurable outcomes specified by the commissioner. The investor is repaid only if these outcomes are achieved.

Outcomes-based contracts (including impact bonds) differ from traditional contracts by focusing on the outcomes, rather than the inputs and activities. Impact bonds are differentiated from other forms of outcomes-based contract by the explicit involvement of third-party investors.

Social impact bonds (SIBs), also increasingly referred to as social outcomes contracts (SOCs), generally refer to IBs in which the outcome payer is the government which represents the target group. This is similar to the INDIGO domestic impact bond, in which all of the outcome payers are located in the same country as service delivery.

Development impact bonds (DIBs) generally refer to IBs in which the outcome payer is an external donor - an aid agency of a government or multilateral agency, or a philanthropic organisation. In practice, DIB is often used interchangeably with what in our INDIGO dataset are identified international impact bonds - those in which at least one of the outcome payers is located in a different country from the service delivery.

However, these broad categories can disguise the diversity in models being used around the world, and many projects do not necessarily identify themselves with, or comfortably fit into, a particular category.

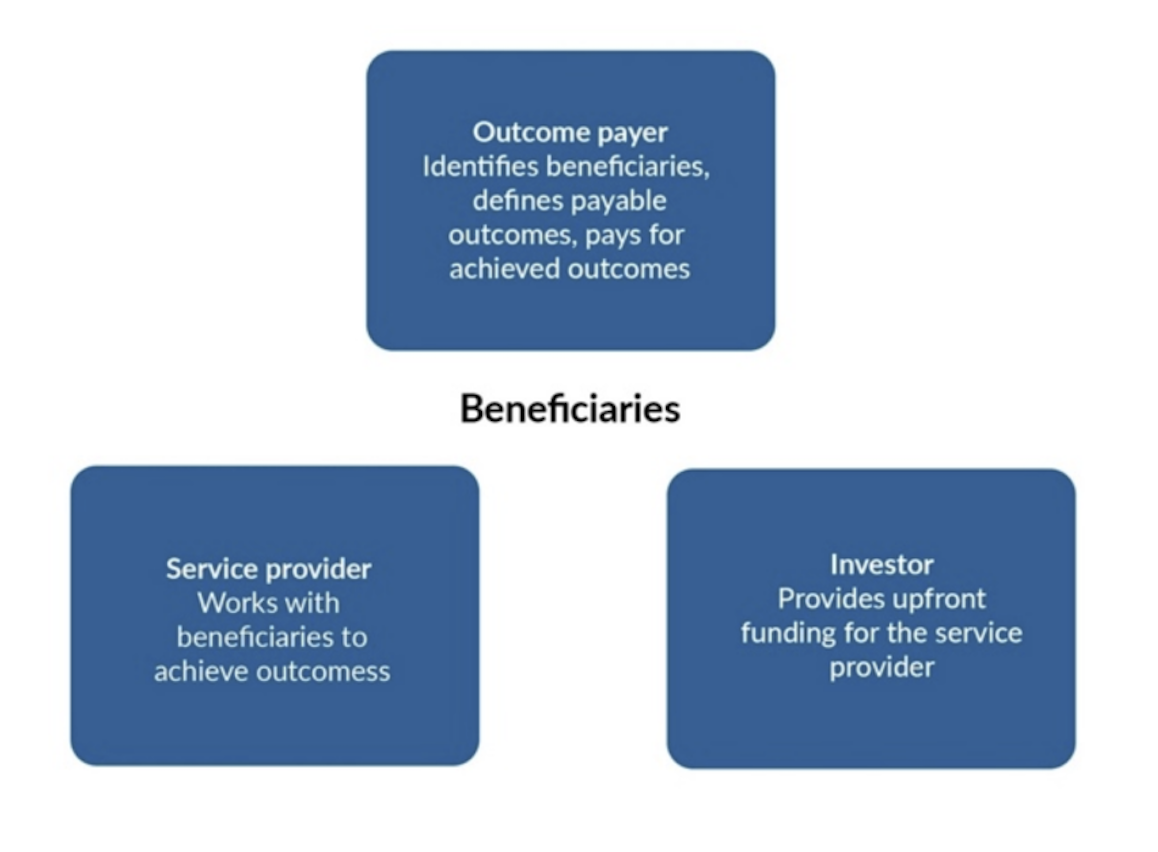

Impact bonds bring together three key partners to deliver better outcomes for a target group: the outcome payer, the service provider, and the investor.

Outcome payers are the commissioners. They identify social issues, specify payable outcomes that must be achieved to address these issues, and pay for achieved outcomes.

Service providers work with the target group to achieve the outcomes specified by the outcome payer, and receive payments based on specified outcomes being achieved.

Investors provide upfront funding for the service provider to finance the project, and are repaid based on specified outcomes being achieved.

The potential benefits and limitations of impact bonds

There are a range of potential benefits that impact bonds might bring to public services:

- Bring together expertise from different fields

- Allow investment in prevention/early intervention

- Enable new interventions to be tried and evaluated

- Enable greater flexibility and resilience in service delivery

- Level the playing field for voluntary sector and NGOs

However, there are also a number of possible limitations to their use:

- Not appropriate in all situations

- Complex and expensive to develop

- Outcomes difficult to define

- May not encourage innovation

- Financialisation of public sector/international aid

Impact bonds are not suitable for every situation, but in the right context can bring a range of potential benefits. Establishing whether an IB is appropriate requires an understanding of the broader evidence around IBs generally. Impact bonds are also being used in different ways in different contexts, so establishing the objective of the project and consideration of the particular factors which may affect whether a particular impact bond might work is important.

In 2018, the GO Lab published a report on all of the evidence from UK social impact bonds (SIBs) to that point. It highlighted three main ways in which social impact bonds may address traditional challenges in the public sector:

- Collaboration – payers and providers can work together to meet citizens’ needs, overcoming fragmented delivery and siloed budgets

- Prevention – facilitate a shift away from short-term reactive public services to earlier intervention, potentially saving money in long-term

- Innovation – risk transfer to investors allows room to try new things

The global evidence base for impact bonds is also growing, as the number of IBs deployed in a wide range of contexts around the world increases. However, at present the evidence for development impact bonds (DIBs) in low- and middle-income countries remains more limited than that for social impact bonds (SIBs) in high-income countries.

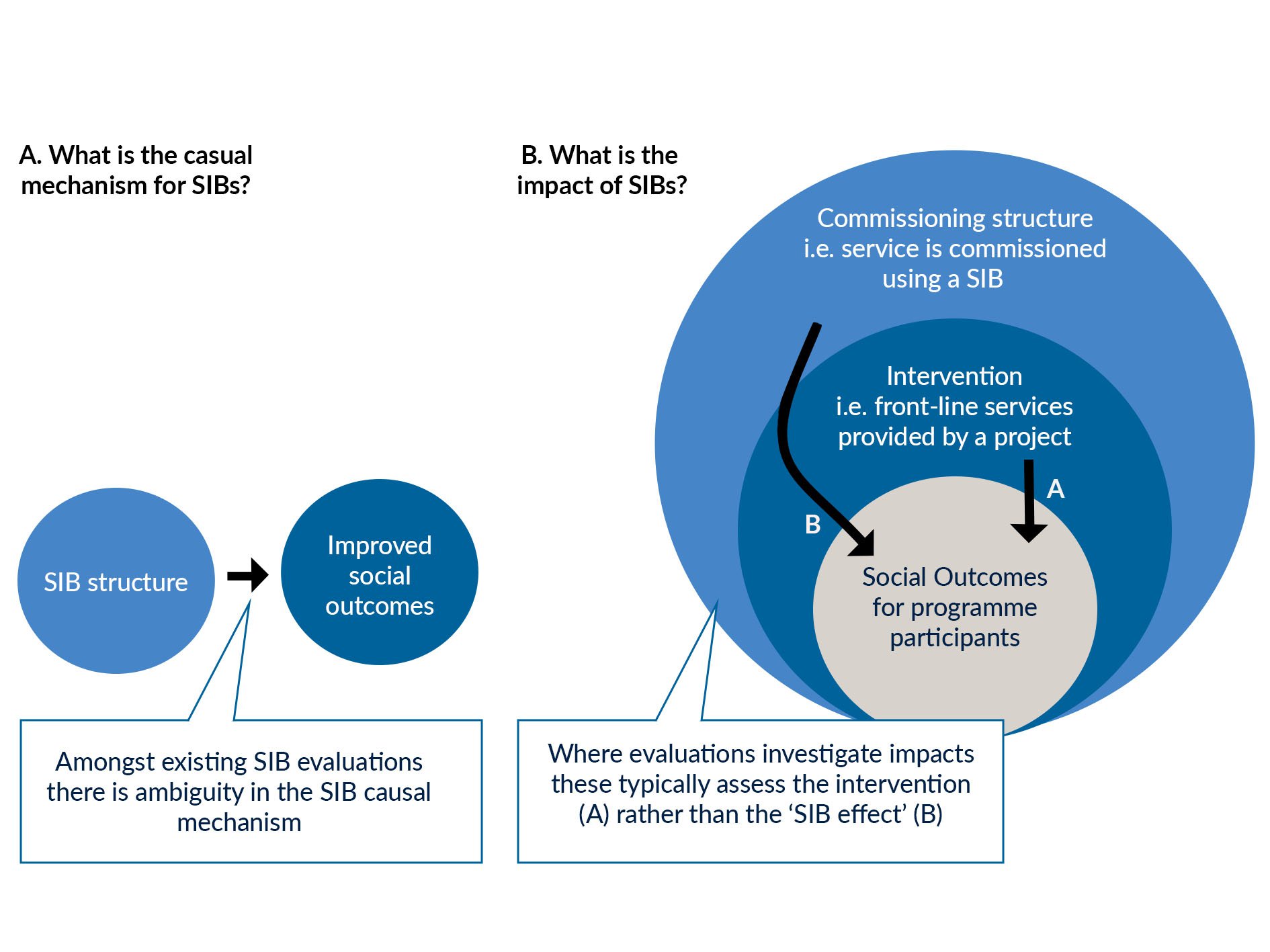

There are limitations to the evidence surrounding impact bonds. In particular, it is challenging to disentangle the benefits of a particular contracting or funding method from the benefits of the service itself. Further evidence will be required to properly establish the ‘impact bond effect’.

Do impact bonds offer value for money?

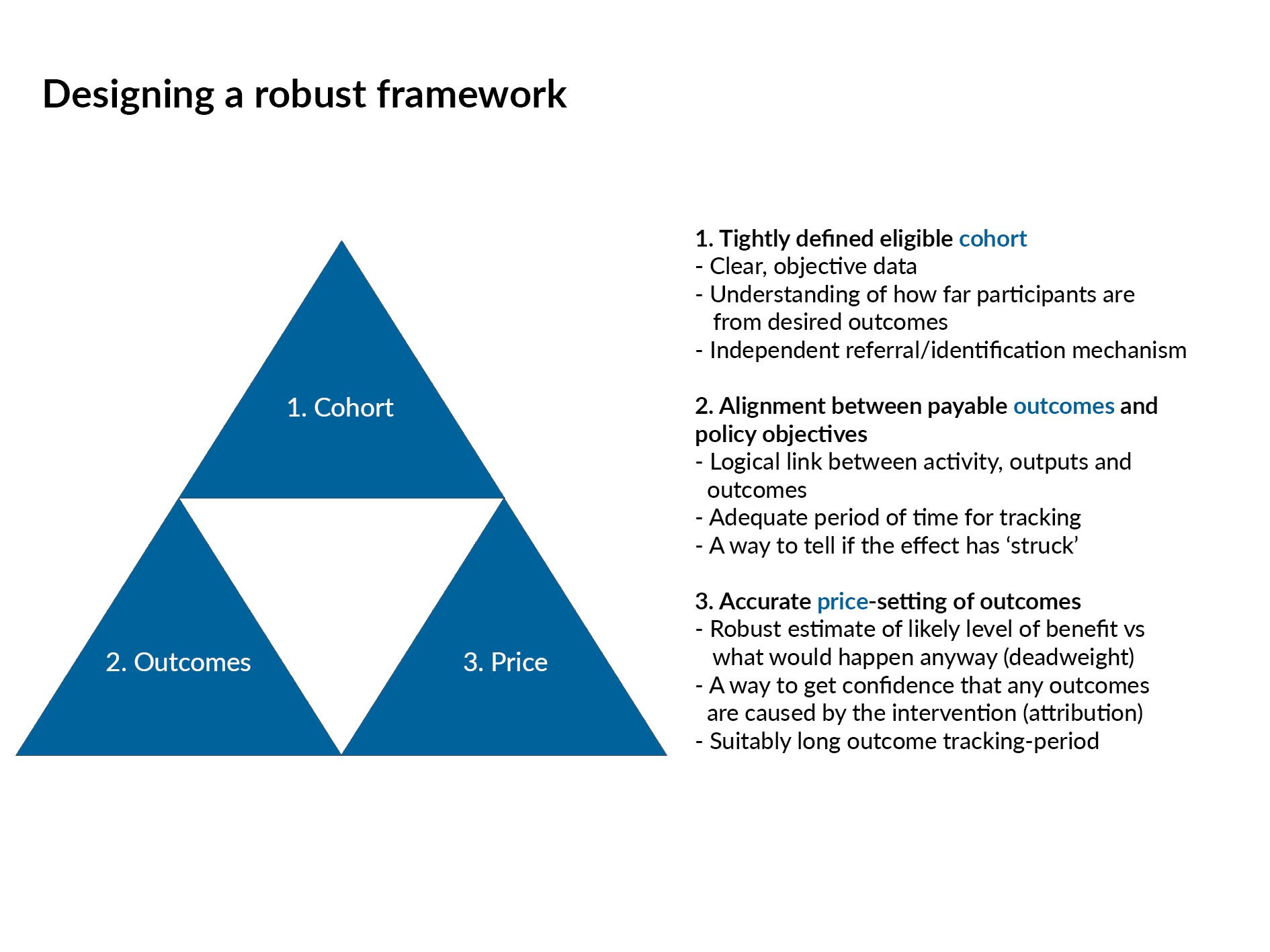

In order to maximise the chance that a particular impact bond will deliver desired outcomes and provide value for money, two things are of particular importance: (1) good relationships are maintained between stakeholders; (2) the contract is robust. The GO Lab has identified three key aspects of a robust contract:

- The eligible cohort must be tightly defined

- There must be close alignment between payable outcomes and policy objectives

- The price-setting of outcomes must be accurate

In practice, the benefits of a tightly specified contract must be offset against the ‘transaction costs’ of developing a contract, and an appropriate balance must be struck.

Key considerations when developing an impact bond

Even if there is evidence that IBs in general may provide a number of benefits, there is no guarantee that those benefits will be achieved in any particular impact bond. There are a number of considerations surrounding the business case, managing relationships and designing the service which may help to establish whether an impact bond is appropriate for a particular set of circumstances.

For more details, read these these frameworks, produced by Social Finance UK in partnership with the Government Outcomes Lab, which examine key conditions and competencies that enable successful delivery of outcomes-based partnerships.

What are impact bonds

5 minute read

This chapter sets out what impact bonds are, the key stakeholders involved and how they have developed over time.

In simple terms, an impact bond (IB) is a partnership aimed at improving social outcomes for service users. The service will only be paid for if and when outcomes are achieved.

A more nuanced definition as set by the GO Lab is as follows: impact bonds are outcome-based contracts that incorporate the use of private funding from investors to cover the upfront capital required for a provider to set up and deliver a service. The service is set out to achieve measurable outcomes established by the commissioning authority (or outcome payer) and the investor is repaid only if these outcomes are achieved. Impact bonds encompass both social impact bonds and development impact bonds.

Impact bonds are different from traditional contracts, such as fee-for-service, or grant-based contracts as they are focused on the outcomes rather than the inputs and activities. For example, an impact bond that is seeking to support young people at school would be more interested in improvements in grades (outcomes) rather than the fact that the children were going to after school classes or seeing a mentor (activities). This is a rather simple premise, but in practice it can be complex as designing a service around outcomes brings new challenges.

As with any contract there is a process of putting the idea into practice. For an impact bond this involves developing the business case, managing relationships, designing the services, planning for delivery. You can view our interactive impact bond lifecycle to see the process in more detail.

Key partners in an impact bond

Impact bonds bring together three key partners: an outcome payer, a service provider, and an investor. In practice, there may be multiple organisations that make up each of these partners as shown below.

Outcomes payer

Outcome payers identify the unmet needs and express a ‘willingness to pay’ for specific social outcomes. Often times the outcomes payer will initiate the impact bond. In high-income countries these are often government departments who are responsible for the specific thematic issue being tackled. In low- and middle-income countries these may still be government departments, but are more likely to be donors who are pursuing positive social outcomes in specific thematic areas. For example:

- In the US, the New York State Department of Labour was the outcome payer for a project to reduce reoffending and offer job training programmes.

- In Uganda and Kenya, DFID (now part of the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office, FCDO), USAID and an anonymous philanthropic fund based in the USA were the outcomes payers for a poverty alleviation project in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Service providers

Service providers offer a service or intervention intended to meet the needs of those beneficiaries and to achieve the outcomes desired. As in other forms of outcome-based contracting, the payment to the provider (wholly or partly) depends on whether outcomes are achieved. They have sometimes been the initiator of the impact bond, but this is less common. The service provider can be a non-profit, and NGO or may even be a private company. For example:

- In West Yorkshire in the UK, Fusion Housing was the service provider in the Fair Chance Fund project to help young homeless people move into accommodation.

- In India, Educate Girls was the service provider aiming to support young girls in Rajasthan to enrol and do well at school.

Investors

Investors provide arrangements to finance the project over its duration, rather than expecting the provider to finance from their own services or from loans with set payment schedules. Repayment to investors is based (wholly or partly) on whether the outcomes are achieved. This protects the service provider from (all or part of) the financial risk. The explicit involvement of one or more investors differentiates IBs from other forms of outcome-based contracting. They may be from foundations, corporates, banks or other private investors. For example:

- In the county of Essex, UK an impact bond sought to create more stable and supportive environments to prevent children from entering care. There were multiple investors, including Big Society Capital, Bridges Ventures, Ananda Ventures.

- In the Democratic Republic of Congo, Nigeria and Mali there was an impact bond to help improve rehabilitation services for those affected by conflict. There were nine private investors coordinated by the Swiss private Bank, Lombard Odier.

Whilst these are the three main partners, there are often other actors involved. They are Intermediaries and Evaluators:

Intermediaries

IBs sometimes use experts to provide specific services, often referred to as intermediaries. They encompass at least four quite different roles.

- Consultant – they will support the contractor to develop a business case for the project that secures internal and external approval to proceed. Consultants most often work on the impact bond before it is implemented and support it to come to fruition.

- Social investment fund manager – manages the funds on behalf of the investors and managers the project with the contractor.

- Performance management expert – who reports on the performance of the IB, providing an independent source of information and scrutiny to investors and the contractor. This might be required if there is a perceived conflict of interest in the provider measuring and reporting on their own performance, or if the provider lacks the skill to deliver the standard of reporting required by stakeholders.

- Special purpose management company – that brings together other parties in a contractual relationship and holds the contract directly with the contractor. They are also known as Special Purpose Vehicles (SPVs).

Evaluators

In many cases there will need to be an independent evaluation to determine whether a project has delivered according to the objectives set out by the contractor. The scale and form of the evaluation required for an IB will need to be decided early. This includes whether the evaluation should be commissioned externally or conducted in-house, either partially or wholly. Read the technical guide on evaluating outcomes-based contracts to give you an understanding of what you are trying to answer in your evaluation and some practical considerations to make.

| In 2017, researchers at the Brookings Institute mapped actors involved in impact bonds in low-and middle-income countries. The research identified 115 entities that were key actors, or providing additional support, in the planning and implementation of impact bonds in low- and middle-income countries. The most common were government agencies, non-governmental organisations and philanthropic institutions. |

|---|

What are the different types of impact bond?

Having explained the definition and key stakeholders of impact bonds, it is important to explain that there are different types and terms used to describe them.

- In the UK they have been referred to as ‘social impact bonds’ (SIBs), or increasingly, 'social outcomes contracts' (SOCs)

- In Europe they are often referred to as ‘social impact partnerships’

- In the US they are known as ‘pay for success’ (PFS) schemes

- In Australia they are often referred to as ‘social benefit bonds’

Whilst there are differences between the way these countries design and develop these programmes, they are referring to the same programme. This guide will speak of ‘social impact bond’ when referring to these programmes as not to confuse the language.

In low- and middle-income countries impact bonds are referred to as ‘development impact bonds’ (DIBs). There is a distinction to be made here that is more than the terminology we use. The difference between SIBs and DIBs is who pays for the outcomes. In a social impact bond, the outcome payer is generally a domestic government, whilst in a DIB the outcome payer may be a donor, such as a government or multilateral aid agency, or philanthropic funding. You can see this distinction in the examples provided above. In practice, DIB is often used interchangeably with what in our INDIGO dataset are identified international impact bonds - those in which at least one of the outcome payers is located in a different country from the service delivery.

How and why did impact bonds emerge?

2 minute read

An overview of why and how impact bonds emerged in the UK and then across the globe.

Starting in the UK

In 2009, UK Prime Minister Gordon Brown, committed the Government to piloting social impact bonds as a new way to fund the delivery of public services. They were proposed as a tool that would be used to tackle the most complex social problems in society, such as homelessness, long term unemployment or children on the edge of the care system. They would do this through bringing together multiple stakeholders and the government would only pay if outcomes were achieved. The idea was that new ideas could be trialled to tackle problems that had no easy solution.

The first impact bond was implemented in Peterborough prison in 2010 to reduce reoffending rates, known as the One Service. This has grown rapidly over the last decade (see our INDIGO Impact Bond Dataset for the latest information). They are working across a range of sectors, such as supporting children on the edge of the social care system, helping homeless people find sustainable housing, and helping integrate refugees into society.

The video below explores how impact bonds have developed since they began in 2010. Dr Chih Hoong Sin is Director at Traverse and has been closely involved with many impact bonds during design and development stages.

Building momentum around the world

As impact bonds began to build momentum across the UK the international community became interested. In 2012, the Center for Global Development (CGD), in partnership with Social Finance, formed a development impact bond working group to explore the feasibility of implementing impact bonds in low- and middle-income countries. This work shifted the potential pool of investors and outcome funders from domestic institutions to international organisations.

In 2013, the CGD/Social Finance working group reported on challenges and benefits of the development IB model. The final report included six case studies to describe potential application scenarios. One of these case studies was the template for the Educate Girls impact bond launched in India in September 2015. In Peru, a few months earlier, the Asháninka Impact Bond launched in February 2015 as the first development impact bond.

The total number of impact bonds around the world is increasing. You can see our INDIGO Impact Bond Dataset for the latest data on impact bonds that have been launched around the world, and an interactive map to explore the data. You can also see the Case Studies for a more in depth look at projects around the world.

Here is a timeline for how impact bonds have developed across the world. This offers a quick snapshot of activities, rather than a comprehensive list. Exact dates are debatable but the timeline reflects consensus where possible.

The benefits and limitations around impact bonds

4 minute read

This chapter will look at some of the potential benefits and limitations of impact bonds, and provide an overview of the emerging evidence around them

Potential benefits of impact bonds

Proponents see impact bonds as an innovative model that can help tackle complex social problems. From this perspective, outcome payers can try new approaches without fearing they have to pay if it is unsuccessful. Investors can help bring new ideas into practice, and providers can improve their practice by focusing on achieving real outcomes. Here is a more in-depth look at the potential benefits. This is not comprehensive, but gives a flavour of the main benefits cited:

- Bringing together expertise – Service providers often have a deep understanding of the beneficiaries and what is likely to work. Socially-minded investors may have both finance and contract measurement experience. Impact bonds allow outcome payers to bring together these competencies. Furthermore, impact bonds often encourage collaboration between service providers and they can work together towards the same umbrella outcome. For example, in the Buenos Aires impact bond, the Forge Foundation, Pescar Foundation, AMIA and Residuca worked together to support young people access skills and employment training so they could secure and maintain jobs.

- Unlocking future savings by investing more up-front. IBs enable contractors or outcomes payers to focus on prevention and early intervention services that might otherwise not get funded. For example, the Healthier Devon impact bond in the UK focuses on reducing the risk of people developing diabetes through making healthier lifestyle choices. Diabetes is a condition that can lead to complications and be expensive for health care providers. If this is effective this could reduce costs in the longer term.

- Enables new interventions to be tried. IBs might provide a way for contractors or outcome payers to pay only for interventions that are effective – and they provide a clear measure of what has been spent to deliver that impact. IBs potentially shift financial risk of new interventions away from the public sector. Whilst investors will do due diligence and seek a track record of performance and explore the evidence base, they may take on risk if it is a new intervention.

- Enabling greater flexibility in delivery of interventions. Unlike traditional methods of contracting, where contracts are designed around a presumption of existing expertise, IBs are designed for contracts where all parties accept a level of uncertainty and the need for change. This balances accountability for achieving outcomes, with the flexibility to innovate and try out new methods of delivering services. This is because by specifying outcomes rather than activities, service providers are free to adjust the way they deliver a service throughout the contract. This flexibility may also support greater resilience, as identified by GO Lab researchers in the response of Life Chances Fund projects to the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic.

- Strengthening and engaging the voluntary sector. One of the originating policy arguments for IBs is that they level the playing field for voluntary or non-governmental organisations (NGOs) in delivering outcomes contracts. This remains a principal consideration where social value and the strengthening of the voluntary sector, as well as economic value, are seen as key priorities. However, it is worth noting that not all impact bonds use non-profit organisations to deliver the service.

Potential limitations of impact bonds

Detractors may see impact bonds as contributing to the financialisaton of services for the most vulnerable populations. From this perspective, outcome payers may see them as complex and expensive option, service providers may feel it is against their ethos, and investors may see them as bespoke and not possible to scale. Here is a more in depth look at the potential limitations, again, this is not comprehensive:

- Impact bonds are not suitable for many cases – They are not a panacea and there are many cases where they are not appropriate, or possible. These include when the contract is small and the expensive set up costs cannot be justified; when outcomes cannot be measured in a meaningful way; or when programmes require immediate action, such as disaster response. There are actually very specific cases when impact bonds are appropriate - the final section discusses these feasibility criteria.

- Expensive to develop – Impact bonds are complex and demand a high level of commitment and capacity. This is often not readily available across the public sector or within donor agencies. Many contracts are small and this can mean that the costs cannot be justified. It is also the case that impact bonds are often bespoke and it is not always possible to scale the service which would decrease the costs.

- Difficult to define outcomes – For impact bonds to work effectively it is essential to identify quantitative and objective outcome metrics. This is very hard to do and often times people will measure outputs rather than outcomes. For example, children registering each day at school is an output, whereas children improving their grades by x amount is an outcome. It is often hard when dealing with complex social issues to identify the right outcomes.

- They may not foster innovation – There is an argument that impact bonds do not foster genuine innovation in providing and implementing services. This may be because investors prefer proven models that have been shown to deliver so they are assured they will get their money back with a return.

- They represent the ‘financialisation’ of the public sector or international aid – This is a highly debated topic and often people often make this from an ideological standpoint. Financialisation refers to a process whereby economic and public policy making are subordinated in favour of the interests of the financial sector. Those holding this position may argue that it is not moral to make profit out of supporting vulnerable people.

The evidence around impact bonds to date

4 minute read

This chapter gives an overview of the evidence around impact bonds, from a UK perspective and then looking to evidence around the world.

Evidence from the UK

As impact bonds began in the UK, a lot of the research has emerged from there. After looking at the state of play of all the social impact bonds to date, the GO Lab produced a report collating all the evidence. This is useful starting point.

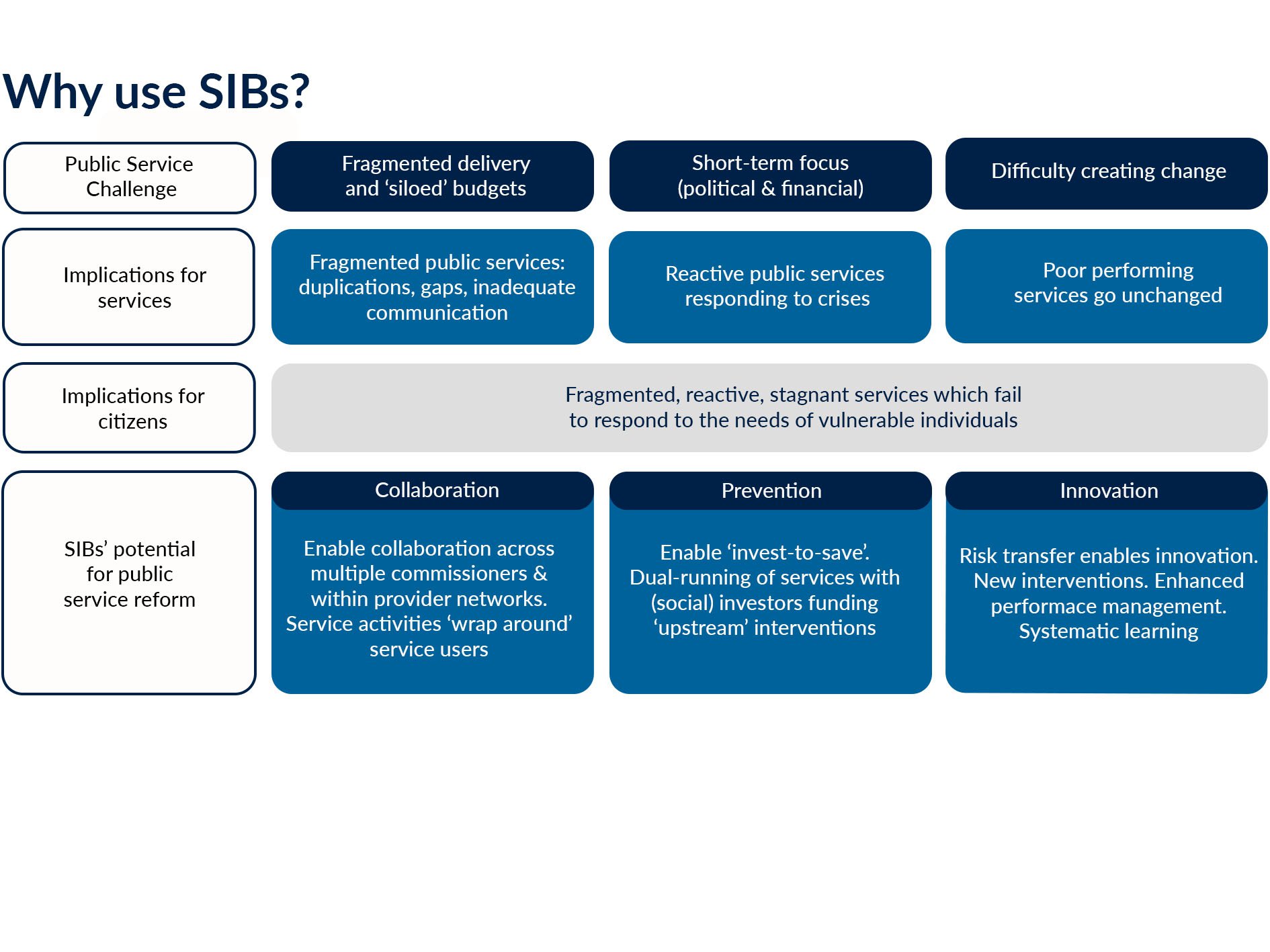

The report was published in July 2018, it is entitled, Building the tools for public services to secure better outcomes: Collaboration, Prevention, Innovation. This report found that impact bonds have the potential to overcome perennial challenges in government which are: the fragmentation of public services, a short term political and financial focus, and difficulty creating change.

The report found that impact bonds may help to reform the public sector through facilitating collaboration, prevention and innovation. The figure below sets out a theory of change which illustrates how IBs may do this and also explains the three factors of collaboration, prevention and innovation.

Collaboration – IBs may encourage collaboration as outcome payers and service providers can work together and ‘wrap around’ citizens to meet their needs.

Prevention – IBs may encourage earlier intervention to prevent a crisis which saves money in the longer term and tackles the root causes of the problem.

Innovation – IBs may encourage innovation as risk is transferred to the investor so there is room to try new interventions or new forms of delivery and performance management.

Understanding the 'impact bond effect'

Rather than asking the question around whether impact bonds work, it is important to consider whether impact bonds are better than other ways of delivering and funding services. Currently, there is no conclusive evidence that impact bonds are better than other ways of delivering public services, such as grants or a fee for service contract. The figure below looks at the challenge of understanding how the impact bond works in the context of how it is contracted, not just whether impact bonds work. Many evaluations do not cover this important consideration.

Evidence from around the world

There is a growing evidence based on impact bonds in low- and middle- income countries. Several reports have mapped and analysed this innovative financing structure. Qualitative analyses focus on interviews to examine the structuring processes, such as this report by the Center for Global Development and this report by Save the Children.

A number of evaluation reports have now been published on DIBs. The Village Enterprise DIB evaluation report shares the results of a randomised controlled trial on the project. The Kangaroo Mother Care DIB report provides an overview of what the DIB achieved, the lessons we learnt and what might come next. And this report presents the findings of IDinsight's three-year impact evaluation of Educate Girls' programme in Bhilwara District in Rajasthan, India. The study found that Educate Girls surpassed the DIB targets for the two core outcomes (learning gains and enrolment). And a recent report by Ecorys and the Government Outcomes Lab synthesises the evidence on education impact bonds in LMICs.

In July 2019, DFID (now FCDO) published an evaluation report of the four pilot DIBs – the ICRC Humanitarian Impact Bond for Physical Rehabilitation, Village Enterprise DIB, Quality Education India DIB, and Cameroon Cataract DIB. This report shed some light on how the DIB mechanism affects the set up and design of development projects. In 2021, a second report was published on the DIB effect during the delivery phase. A future report will examine how the DIB mechanism affects performance and sustainability.

Do impact bonds offer value for money?

For many outcome payers, value for money is an over-riding priority. Good value for money is the optimal use of resources to achieve the intended outcomes. In the UK, the National Audit Office (NAO) uses three criteria to assess value for money of government spending: economy, efficiency and efficiency.

While IBs can be costly to develop, there are a few ways that a well-designed IB might help to ensure value for money:

- The outcome-based payment element can mean that contractors will not pay, or will pay less, if the work does not achieve the specified outcomes.

- Given the requirement for evidence of outcomes achieved, IBs can contain a natural evaluation element. Applied adeptly in the longer term, this allows organisations to build evidence around ‘what works’ and ensures future interventions can achieve greater value for money.

- The development of an IB demands precise definition of target cohort, desired outcomes, and payment amounts, and includes elements of cost-benefit analysis, which all helps to ensure that interventions are supported by a robust business case.

- The involvement of a third party in the form of an investor who risks losing money can bring in an added dimension of performance management, above and beyond what contractors have the capacity to perform on their own.

Unlocking this value for money depends on a combination of sound design of the contract terms, and good quality relationships between the different sets of stakeholders. Forthcoming GO Lab research suggests three aspects of a contract that should be tightly specified in order to have assurance a contract will deliver value: the cohort, the outcomes, and the price of the outcomes (see "Designing a robust framework" below). However, the degree of technical know-how and stakeholder negotiation required to define this ‘outcomes specification’ in detail needs to be balanced with the time and resource available to develop and launch the contract (the so-called ‘transaction costs’).

You can read more about these considerations in our technical guides on Setting and Measuring Outcomes and Pricing Outcomes. You can also understand more about the different terms used in our glossary.

Top five publications to read

There are many different publications that look at impact bonds and the evidence to date. There are many more in our Publications Library, but here are our top five to read:

- Building the tools for public services to secure better outcomes: Collaboration, Prevention, Innovation, the GO Lab’s first publication, looking at the state of play in UK social impact bonds. Government Outcomes Lab, 2018.

- FitzGerald, C. et al. (2021). Resilience in public service partnerships: evidence from the UK Life Chances Fund.

- Ronicle, J. et al. (2022). Commissioning Better Outcomes Evaluation 3rd Update Report.

- FCDO & Ecorys (2021). Findings from the second research wave of the independent Evaluation of the FCDO Development Impact Bonds Pilot Programme.

- Tan, S. et al. (2019). Widening perspectives on social impact bonds.

Key considerations when developing an impact bond

5 minute read

This chapter will look at what you need to do to make sure your impact bond is feasible. For more details, read these these frameworks, produced by Social Finance UK in partnership with the Government Outcomes Lab, which examine key conditions and competencies that enable successful delivery of outcomes-based partnerships.

Now you understand what an impact bond is and whether it sounds like something you would like to pursue, it is important to consider whether it is actually feasible. You will need to consider both the technical processes involved and the relationships that need to be built and nurtured. Knowing whether your impact bond is feasible can be a challenge, but is crucial to avoid extra challenges further down the line. Here is a checklist of things you need to consider:

When developing a business case, can you confirm…

- there is a clear reason to use an impact bond – It is crucial to be clear and explicit about the reason for using an outcome-based contract rather than a more conventional form of contract. In our Report, Building the Tools, we outline three reasons why IBs may be a useful tool for public service reform: a way to overcome fragmented delivery (though collaboration), a way to reduce demand for high-need intensive services (through prevention), and a way to disrupt the usual way things are done (though innovation). Before going any further, an outcome payer should be clear whether any or all of these are desired benefits.

- there is time to develop it – Impact bonds vary in the time they take to develop. Some have been made in three months, but others have taken a year or more. If the response required is urgent, e.g., disaster relief, an impact bond would not be appropriate. Outcome payers need to consider whether the time period is appropriate.

- there is budget to pay for it – Outcome payers should have a clear idea at the start of where the money to pay for outcomes is likely to come from. A link will need to be made between the type of outcomes which might be paid for and the budget line. This is because it is common that budgets will be specified according to service or policy areas rather than outcomes. Whilst the budget for outcomes is crucial, it is also important to consider how much it will cost to set up your impact bonds, such as a feasibility work, design and development.

- outcomes can be measured – It is essential that there is consensus around the high-level outcomes that outcome payers are willing to pay for. They must be meaningful and measurable, and achievable within the time period given. For example, a young person is in employment can be confirmed by their employer. Read the Setting and Measuring Outcomes guide for specific guidance.

- good outcomes wouldn’t have happened anyway – Whilst this is tricky to do in practice, it is important to be sure that the outcomes being paid for wouldn’t have just happened anyway, even without the programme. This is known as measuring the counterfactual, it compares what happened within an impact bond and what might have happened if there was no service. For more information about developing the counterfactual look at our guide on evaluating outcomes-based contracts.

- there is a well-defined set of service users – The cohort of service users must be made up of people with historically negative outcomes and the outcome payer thinks that better outcomes can be achieved through an impact bond. The cohort must be clearly and unambiguously defined so that there’s no danger of the service provider ‘cherry picking’ individuals that might achieve better outcomes. This clarity is also equally important for the provider and investor as a poorly defined cohort or high dropout rates may lead to additional costs to achieve each outcome.

- the contract is large enough to justify the set-up costs – The value and length of the contract also needs to be sufficient to offset the time and cost of setting it up. associated with management and governance of the contract, which may be higher than for other forms of contract. Our Project Database gives some indication of the typical size and duration of contracts. Many people believe impact bonds would be more effective if they were larger.

When managing relationships, can you confirm…

- there is internal capacity and commitment – One of the main causes of outcomes contracts not achieving a successful contractual outcome is the lack of senior engagement and commitment from stakeholders. The contractor needs to establish an effective project team from the start, committed to the IB intervention.

- the provider market has appetite – Contractors should consider the type of providers they wish to engage, and the sort of relationship they wish to have with them. There are examples of IBs that use both large, national providers and small, local ones. Equally, there are examples of IBs where there is a highly trust-based relationship with providers; conversely, some have relied more heavily on the contract terms as written (though some evidence appears to suggest this can be problematic).

- the provider market has capability – As well as provider appetite, you should explore provider capability to deliver in this way. This can be done through pre-tender market engagement. It is also important that there is a likely supply of risk capital. This is particularly important where there is no established provider or social-investment backed market, or there is concern about the viability of the service being run through an impact bond. It must be appropriate to give service providers the freedom to deliver the service in accordance with their own methods.

Outcome payers may seek to explore:

- the level of understanding amongst expected providers of outcome based contracting or impact bonds, and the rationale for using these approaches;

- whether these providers are likely to respond positively to payments being linked to the achievement of outcomes.

Contractors may seek to explore:

- the quality of experience and capacity available, and the possible role of an intermediary;

- interest from investors and whether they see the project as a viable investment;

- the best way to engage the market when developing the business case and during the formal procurement phases. These processes are explained in the awarding the contract for an impact bond.

When designing the service, can you confirm…

- the contract will integrate with those services if they are already in existence – In high income countries there is likely to be a range of public services available. The proposed impact bond contract needs to integrate with existing or proposed services. There may be organisational and/or cultural differences that challenge the relations between other teams in related public services. Consideration should also be made around the confidence in local residents or service users in the proposed service. In low- and middle-income countries this point may not be relevant as public services may be less established. However, it is important to understand the field, e.g. by asking if there are other aid organisations or NGOs working in this space.

- there are indications that effective interventions exist – There must be either an existing evidence base, or a robust ‘theory of change’, for possible interventions which might meet the identified population need. This means even if you don’t know what will work, there should be a strong logic to show what might work. If there is a range of possible interventions which are well proven, and there are providers who have shown they can deliver them effectively, there is probably no need for an IB – a straightforward service contract might do. Conversely, if there are few interventions, they are unproven, or providers are weak, investors may deem the IB contract too risky to make or back any bids.

Moving beyond the basics

1 minute read

What has been done elsewhere?

Impact bonds relatively new, complex and it may be hard to find impartial advice. If you are interested in impact bonds and want to see what else has been done across the world you can look to our knowledge bank:

- Case studies – We have a range of case studies that cover many different policy areas and issues. We capture information and data on impact bonds across the world, including the UK, India, Buenos Aires and more.

- Projects database – We have captured data on projects from around the world and have an interactive map that you can explore. The data includes the target population, capital raised, intervention description and outcomes and much more.

How can I design and develop an impact bond?

If you are interested in designing and developing an impact bond you may need more technical support. We have a range of online guidance available in our toolkit:

- Technical guidance – We have many guides that are created by experts, peer reviewed and written in an accessible way. They will help with setting and measuring outcomes, pricing outcomes, evaluating outcomes-based contracts, and awarding outcomes-based contracts.

- Impact bond lifecycle – This interactive tool will help you explore how an impact bond works, from ensuring it is feasible, through to implementing it and then evaluating it.

If you are interested in speaking with one of our team about impact bonds, we invite you to get in touch with us at golab@bsg.ox.ac.uk. You may have a specific question, something about the technical process, or a challenge you have come up against.

Acknowledgements

1 minute read

The GO Lab has put together this guide with help from many members of the team. We are also grateful to MAZE who reviewed the document and provided useful comments.

We have designated this and other guides as ‘beta’ documents and we warmly welcome any comments or suggestions. We will regularly review and update our material in response. Please email your feedback to golab@bsg.ox.ac.uk.