Evaluating outcomes-based contracts

This guide explores how to evaluate an outcomes-based contract and the practical considerations that need to be made

Overview

2 minute read

In outcomes-based contracting and impact bonds there is a real focus on making an impact - the aim is to achieve the best outcomes for the people on the programmes. As with any social programme, especially a new or innovative one, conducting a good evaluation can help us understand the impact of the programme, whether things need to change during delivery, adapted for next time or stopped altogether.

There is a lot of advice about evaluations from government bodies, voluntary sector, donor agencies and researchers. Each country will have their own guidance on evaluation that will suit the context that the impact bonds are being developed in, and will highlight specific and relevant considerations. This guide is not meant to duplicate or capture everything in those documents. Rather, it will highlight the key considerations and strategic decisions you need to make. It will also point out what may be different about evaluating impact bonds as opposed to other programmes and point you to further information.

Formative evaluations identify which aspects of the service are working well and which are not. This informs changes to improve the service.

Summative evaluations look at the overall programme, to examine why it worked well (or did not), to prove what should happen with the programme going forward.

Monitoring tracks the progress of the programme to check whether things are going to plan. It may be conducted as a more formal process of performance management, which ensures specific milestones are being met.

Process evaluations look at how the programme has been implemented, and whether different aspects of the theory of change are working as expected.

Outcomes evaluations examine whether the overall goals of the programme have been achieved (including those outside of the scope of payments).

Impact evaluations compare the outcomes of the programme to what would have happened if there had been no intervention, to establish what impact was achieved.

Cost-benefit analysis assesses whether the benefits of the outcomes achieved by the programme were worth the costs required to achieve them.

Developing an evaluation strategy

In order to develop an effective evaluation strategy, a well-defined theory of change is required. This fills in the gaps between the intervention and desired outcomes, to illustrate how and why the change is expected to happen. In terms of evaluation, it helps to identify which aspects of the programme should be evaluated and for what purpose.

Having selected the areas of the programme to evaluate, these must be narrowed down to identify key questions that the evaluation will set out to answer. They should be developed collaboratively to reflect the goals of the organisation.

It is important to set the scope of evaluation. Outcomes-based contracts can be evaluated at different levels – you can look at the front-line service, or you can look at a higher level at the effect of the contracting and funding arrangements.

High quality data is key to a good evaluation. The exact types of data required will depend on the questions and methods used. It may be collected already, as part of the programme or by other agencies. Alternatively, new data may be needed to support the evaluation. It is also important to consider data protection regulations may affect the use of data.

A range of resources will be needed to ensure a successful evaluation process. These include financial and management costs, analytical experts, engagement with providers and wider stakeholders, as well as the costs of peer review and dissemination of findings.

Evaluations can be conducted in-house or contracted out to an independent evaluator. Independence gives the findings credibility, particularly with external stakeholders.

Publishing the evaluation provides a useful resource, helping others to understand the benefits and challenges of the approach, and expanding the evidence base more generally.

Back to basics - introduction to evaluation

4 minute read

Before delving into how to conduct evaluations, it is important to discuss what exactly we mean when using the word ‘evaluation’. People often use the term evaluation to mean a variety of things, which can cause confusion. For this guide we define evaluation as follows:

In its broadest sense, evaluations examine how a policy or intervention was designed and carried out and what impact this had at a range of levels (such as at the beneficiary level, at the service provider / public body level and on the wider delivery ‘system’). Evaluation can employ a wide range of analytical methods to gather and assess information. The choice of methods adopted will depend on a range of factors, particularly the type of question to be answered, the design of the programme, available resources, and the level of rigour stakeholders wish to be within the evaluation.

Purpose of evaluation

Evaluations can be formative or summative. The simple table below highlights the definitions.

| Purpose | What does it mean? |

|---|---|

| Formative ...to ‘improve’ | “Designed, done, and intended to support the process of improvement, and normally commissioned or done by, and delivered to, someone who can make improvements” |

| Summative ... to ‘prove’ | “Done for, or by, any observers or decision makers (by contrast with developers) who need evaluative conclusions for any reasons besides development” |

As stated, formative evaluations are trying to improve policies or interventions. They are often done by managers or others who have good knowledge of the programme. Based on these evaluations they can make amendments to improve the design or performance.

Alternatively, summative evaluations look at the programme as a whole and take more high level decisions, such as expanding or cutting a service. They often happen externally after a programme has finished, to understand why a programme works or does not, and what factors were involved in its success or otherwise.

Types of evaluation

There are many different types of evaluations, and it may not seem clear which one to choose. It is best to start by thinking about the questions you want the evaluation to answer.

The table below highlights the different types of evaluations and the questions they seek to answer. You can find more detailed information and examples of different evaluation options at Better Evaluation: decide which method - https://www.betterevaluation.org/en/start_here/decide_which_method

| Type | What questions are you asking? |

|---|---|

| Monitoring | Is the implementation progressing as planned? |

| Performance management | Are milestones being achieved? |

| Process evaluation | How is the policy implemented? Do we observe expected behaviours? Why? Why not? |

| Outcome evaluation | Has the policy achieved its intended goals? |

| Impact evaluation | Did the policy produce the intended effects compared to what would have happened anyway? |

| Cost benefit analysis | Are the policy benefits worth the costs? |

Monitoring is a process of observing and checking in to see if things are going to plan. This may involve collecting, analysing and using information to track progress.

Performance management is a more formalised process of monitoring to ensure that objectives and milestones are being reached in an efficient and effective way.

Process evaluations look at how the programme has been delivered and the processes by which it was implemented. A process evaluation may be conducted periodically throughout the life of the programme or to look back over the programme.

Essentially, it looks over the different aspects of the theory of change (e.g. activities, inputs, outputs, see Chapter 3 for more information) to understand where things went well and where improvements should be made. It usually includes primarily qualitative (e.g. interviews) data in order to understand what happened at each stage of the programme, but can include quantitative (e.g. statistics) data (for example, analysing the monitoring information to understand progress).

Outcomes evaluations look at whether the programme has achieved the set goals. They may not appear relevant for impact bonds as measuring outcomes is integral to the programme. However, many impact bonds look at outcomes beyond the ones that will be paid for so this is important to bear in mind. An outcome evaluation is also relevant for impact bonds because they look at beyond whether beneficiary outcomes were achieved, and can examine whether the original goals of the impact were achieved, such as whether the impact bond enabled the public body to pursue an early intervention strategy.

Impact evaluations provide information about the impacts produced by the intervention. There is a need for a counterfactual – an estimate of what outcomes would have occurred without the intervention. This is so you can compare what would have happened without the impact bond. They must establish what has been the cause of the observed changes, referred to as the causal attribution.

An impact evaluation is most often used for summative purposes. It can help understand ‘what works’ and can then be useful to understand whether this will work for different groups in different settings.

There are a range of methods that can be used in impact evaluations. They can include ‘experimental’ methods, such as Randomised Control Trials (RCT), where some beneficiaries are randomly allocated the intervention (known as the treatment group), and some are not (control group), and outcomes between the two are compared. They can also involve ‘quasi-experimental’ methods, where a comparison group of similar people to the beneficiary group are identified, and the outcomes of the treatment group are compared with this comparison group.

Cost benefit analysis looks to understand all the results from the data that has been gathered. It makes estimations the strengths and weaknesses of an approach and monetises this to see whether the costs are worth paying for the benefits received.

For more information about evaluation criteria and definitions see the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) Development Assistance Committee (DAC) criteria and definitions.

OECD DAC Network on Development Evaluation- https://www.oecd.org/development/evaluation/

Dispelling myths around evaluations

3 minute read

There are many myths and misconceptions around evaluations and impact bonds which this chapter seeks to dispel. If you feel ready to start developing your evaluation strategy, read chapter 3.

Myth: Impact bonds already measure outcomes so I don’t need to evaluate them

Reality: Measuring outcomes is not enough to know the impact of the programme

For an impact bond, the ‘outcomes’ of a programme will be set out clearly, often with a payment made following the achievement of that outcome. However, measuring the outcome alone may not show you what would have happened to the individuals if the programme had not been delivered. Therefore, it may be wise to consider implementing an impact evaluation to have a full understanding of the additionality of the intervention – that is, the outcomes that would have been achieved over and above those that would have happened anyway.

Whilst it is important to acknowledge that some impact bonds do make payments on the basis of improvement against a counterfactual, this does not provide a complete picture. There may be a wider set of outcomes achieved than what has been paid for that need to be evaluated. For example the evaluation may help us understand whether the proves has worked effectively or not or whether we can achieve earlier interventions. For many of the UK outcomes funds, understanding whether there has been growth in the social investment market has been part of the evaluation, something that is beyond just looking at the outcomes.

Knowing whether a programme made an impact or not, and how effective the processes were, generates evidence for programme leaders or donors. They can use this evidence to decide whether to run programmes or not and make more informed decisions.

Myth: Evaluations are expensive

Reality: you can fit an evaluation to your budget

Evaluations come under a range of price brackets depending on what type you choose and what you are trying to find out. Commissioning a robust evaluation will be more expensive than completing one in house. However, commissioning a robust evaluation may not be the most appropriate option for your programme. Checking what data is already available and the capacity and skillset in your workplace can save costs. You can then work the evaluation into your overall budget.

See chapter 4 for more information on the practical considerations, such as resourcing and costs.

Myth: Evaluations are a bolt on

Reality: Evaluations are an integral part of good contracting

For government or donor agencies, decisions about adopting programmes will need to be justified based on the evidence available. Evaluations can help with these high-level decisions by identifying where services are effective and should be adopted and scaled up, and where programmes are ineffective and should be adapted, scaled down or stopped altogether. Evaluations are part of good contracting and should be considered business as usual.

Furthermore, as impact bonds are a relatively new and small part of public policy or donor programmes, evaluations are an integral part of the learning process. We can build evidence and work out whether and how they are a useful tool or not.

Myth: Evaluations are a test and add unnecessary pressure

Reality: Evaluations are a way of learning and improving practice

Many people see evaluations as another way of measuring performance. They may believe the evaluation will reflect on them individually or as a group as though they are being scrutinised. However, evaluations should be viewed as an opportunity for learning and improving programmes and policies.

Evaluations can help build greater understanding of relationships and ways to develop them. They can be about improving processes and making them more efficient. Deciding not to conduct an evaluation would risk missing opportunities to learn from both successes and failures. Perhaps the real failure would be a failure to learn.

Myth: Evaluations take a long time

Reality: Evaluations can suit your timeframe

There are many different types that can suit your timescale and fit the resources you have available. When developing your evaluation, you can plan the timeframe that suits you. Look at chapter 3 for more practical considerations, such as resourcing your evaluation.

Myth: Evaluations are only useful at the end of a programme

Reality: You are not restricted to conducting an evaluation at the end

Summative evaluations, such as impact evaluations can help to give an end look at the programme and help inform future decisions. However, formative evaluations such as monitoring and performance management can give you updates along the way. This can help you realign your programme to the goals and outcomes that are set out at the start.

Myth: It doesn’t make a difference if to national policy if I do an evaluation or not

Reality: All evaluations are useful to add knowledge and influence future policymaking

The debate around impact bonds is highly polarised and sometimes based on ideology or media bias rather than evidence. Conducting evaluations can allow for greater understanding of the model, where it may work and whether there are gaps in knowledge. It also can inform us about how successful programmes are being delivered and whether certain tools are more successful than others.

Developing an evaluation strategy

6 minute read

This chapter will look at the way to put together an evaluation strategy. It will explore how to develop a theory of change, how to identify the research questions and how to set the scope of the evaluation.

There is no one size fits all approach to evaluation, and designing and conducting an evaluation can be a learning process within itself. Whilst there are many examples of what ‘good’ looks like, Preskill & Jones (2011) state a good evaluation will seek to:

- establish the boundary and scope of an evaluation and communicate to others what the evaluation will and will not address;

- ask the broad, overarching questions that the evaluation will seek to answer; they are not survey or interview questions;

- reflect diverse perspectives and experiences;

- be aligned with clearly articulated goals and objectives; and

- ask questions that can be answered through data collection and analysis.

Theory of change

An important step in developing an evaluation strategy is to have a well-defined theory of change, also known as a logic model. A theory of change is a comprehensive description and illustration of how and why a desired change is expected to happen in a particular context.

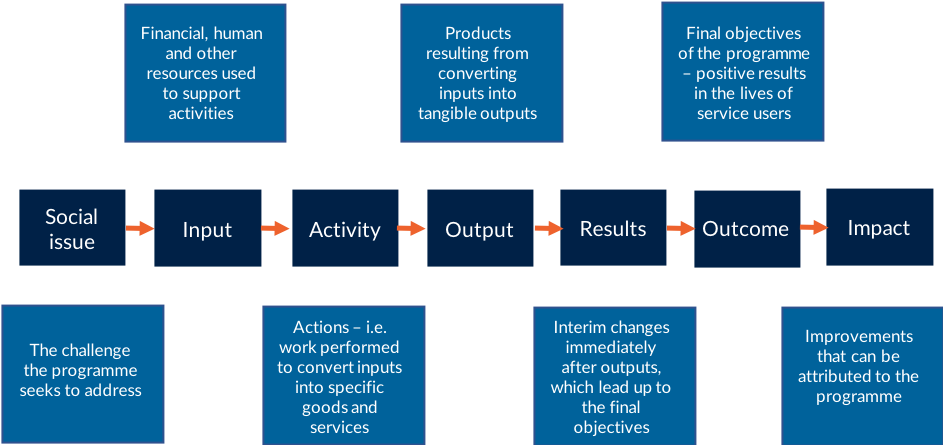

As seen in Figure 1 below, a theory of change identifies the inputs, activities, outputs and outcomes of a programme. Essentially, it fills in the part that is missing between the activities (what the programme does) and how this leads to the desired outcomes (what the programme hopes to achieve).

A theory of change is not a representation of reality, it is a tool that can help organise our thinking. It can help in the allocation of resources, such as money and staff.

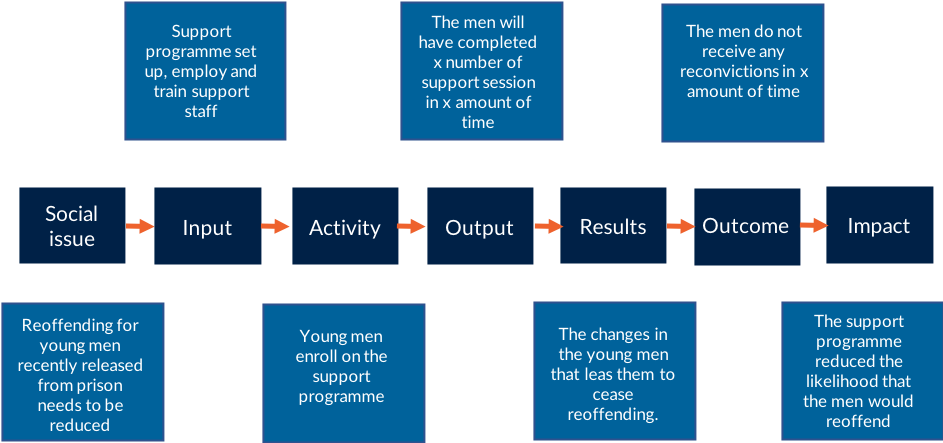

Using a simple example, an impact bond might hope to reduce reoffending in young men who have recently been released from prison. This is shown in the theory of change figure below.

The theory of change can help us identify what we want from our evaluation. If we want to cut the theory of change and examine different aspects we might want to choose a formative evaluation. This can help us understand, for example, whether the resources are appropriate for the activities that need to be carried out.

Alternatively, we might want to look at the theory of change as a whole and conduct a summative evaluation. This kind of evaluation can help build an understanding of whether the causal links hold together and can inform us about the impact of the programme.

See the UN Development Group companion guide to creating Theory of Change for more information.

Identifying the research questions

At an early stage, it is important to set out the questions that the evaluation will seek to answer. As stated, your theory of change can help you see the different parts of the programme that you want to know more about. It is now time to narrow it down to some key questions. Remind yourself of the questions in the types of evaluation questions in chapter 1 and consider what you want to ask.

Your evaluation questions should be in line with your goals as an organisation. Deciding on the questions is best done through bringing together different voices in the organisation. Those designing and implementing the programme, and analytical colleagues, who will be involved in developing and conducting the evaluation, should usually develop research questions jointly. This is an iterative process and may take multiple conversations to get right.

For example, the Youth Engagement Fund (YEF) evaluation in the UK measured both process and impact. Here are a few of the research questions they used as part of their evaluation framework.

| Theme | Research question |

|---|---|

| Referral and engagement | How are young people being referred to the projects? How effective are the different referral routes in targeting the right people? |

| Effectiveness of delivery | How effectively are the projects being delivered? |

| Overall | What are the main advantages and disadvantages of commissioning through a SIB? |

| Engagement and development | What was the rationale for the stakeholder groups becoming involved? |

| Outcomes and metrics | Did data systems enable effective measurement of performance without significant dispute between parties or leading to perverse incentives? |

| Payment model | Did financial returns match expectations? |

| Impact of SIB in intervention delivery | Did the fact that the intervention was funded through a SIB affect delivery progress? How? |

| Objective or theme | Research question |

|---|---|

| Objective - support the development of the social investment market, build the capacity of social sector organisations and contribute to the evidence base do SIBS |

Has being involved in a SIB increased the capacity of the service provider to bid for other contracts? In what way? What impact have the projects had on the capacity of social enterprise organisations? |

| Innovation | Has the SIB led to more innovative and efficient support? |

| Financial savings | Did financial savings/returns match expectations and the levels predicted at the development stage? If not, why not? |

| Efficiency | What could have been done differently to lead to greater innovative, efficient and effective delivery? |

Another example is the Department for International Development (DFID) DIBs evaluation completed by Ecorys. This focused on the ‘DIB effect’ rather than the intervention. Here are some of the evaluation questions they sought to answer in the evaluation. You can read more detail in the final chapter of this guide which looks more closely at this case.

| Question | Sub questions |

|---|---|

| Assess how the DIB model affects the design, delivery, performance and effectiveness of development interventions |

To what extent were the three DIB projects successful in realising their aims, output, outcomes and impacts? Where was the DIB model most effective? How does the effectiveness compare to other DIBs and funding mechanisms and why? |

| What improvements can be made to the process of designing and agreeing DIBs to increase the model’s benefits and reduce the associated transaction costs? |

What (if any) are the extra costs of designing and delivering a project using a DIB model and how do they compare to other funding mechanisms? How does the efficiency compare to other DIBs and funding mechanisms and why? Do the extra costs represent value for money - to what extent do they lead to additional results, impacts and benefits? |

Setting the scope of the evaluation

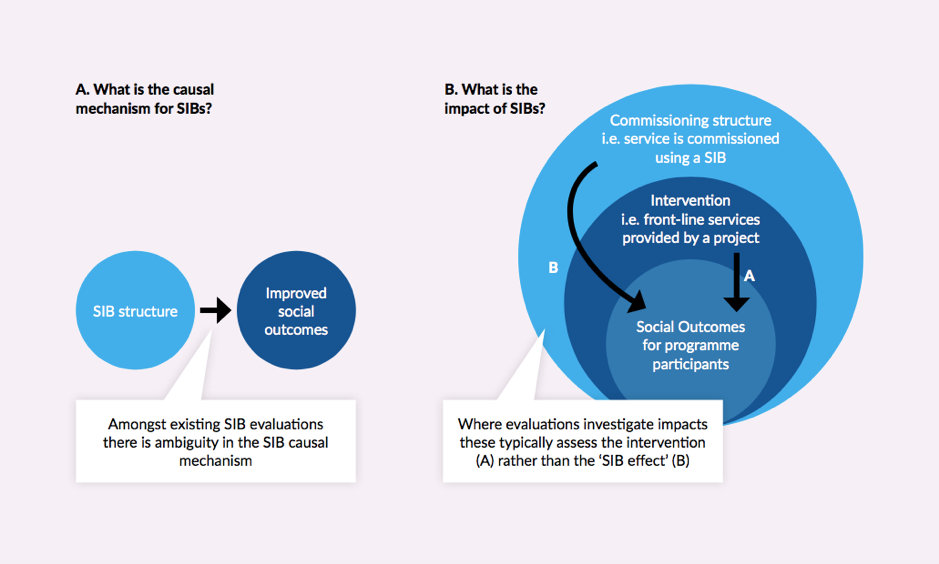

When deciding on your evaluation it is important to work out the scope. At what level are you pitching your evaluation? Questions around scope come back to what you are trying to learn from your evaluation.

The table below is from Gustafsson-Wright et al, 2017. It suggest the different approaches based on scope/focus of the impact bond.

| Project focused on | Measurement |

|---|---|

| Innovation | Non-experimental |

| Building evidence | Quasi-experimental or experimental |

| Replication, drawing on an established evidence base | Against a counterfactual to further build evidence |

| Scaling, using established, highly evidence-based interventions | Simpler methodology |

Evaluations can have a small scope, looking at the success of the impact bond as an intervention. This may involve performance management and looking at how well the processes work for the impact bond. It is essentially an appraisal of the impact of the service.

Evaluations can also look at the programme at a higher level, looking at the success of the impact bond as a contracting structure. This would look at how the impact bond compares to another way of contracting a service. For example, does contracting an impact bond achieve better outcomes than commissioning a grant-based approach?

The figure below highlights the different levels that you can evaluate your impact bond at. It explores the challenge, or ‘double trouble’, of evaluating the impact bond as an intervention versus evaluating the impact bond as a contracting (sometimes known as commissioning) structure.

The challenge is that if you evaluate your impact bond as an intervention, even if you know the outcomes for the beneficiaries were successful, you don’t know whether this would have been more or less successful with a more conventional contracting structure, like a fee for service contract or a grant. Were the outcomes achieved because of the impact bond or something else?

For example, for the Peterborough One Service impact bond in the UK, the evaluation was at the level of the intervention. There was a robust impact evaluation that looked at whether the outcomes could be attributed to the impact bond intervention. The evaluation found that outcomes had improved and reoffending was reduced compared to a nationally constructed comparator group. The question is whether this was because of the impact bond (i.e. the outcome-based contract and involvement of a social investor) or was it because of other factors, such as the intensive collaboration between voluntary sector organisations? It may be the case those other factors would have been seen even if the service was paid for through a grant or paid for the activities carried out.

We don’t have all the tools to get under the skin of this tough question. However, it is worth considering when it comes to evaluating your programme. To start with you will need to estimate what things might look like in other contracting mechanisms, or look at where similar interventions have been delivered through alternative mechanisms and do a comparison.

The DFID DIBs evaluation measures the ‘DIB effect’ and sets out an evaluation strategy. It will helpful to reference this guide is you are aiming to understand these broader effects.

Practical considerations

5 minute read

There are many practical things that you will need to consider when developing an evaluation. It is important to consider the availability of data, resources available, and whether the evaluation will be contracted out or completed in house. This chapter will cover the key considerations you need to make in order to complete a robust evaluation.

Knowing the data requirements and availability

A good evaluation relies on high quality data. You will need to consider what data is required during the design and development of the impact bond. This is to ensure that you have a baseline to measure against before the programme begins. If you do not do this your evaluation may be severely hampered.

The evaluation questions and method will determine the type of data that needs to be collected. For example, robust impact evaluations that are looking to understand casual links between the programme and the outcomes will require a lot of high-quality data. This needs to be sufficient to estimate a counterfactual. Process evaluations that look at which parts of the programme and how well they worked may need qualitative data. They may conduct in depth interviews to understand the dynamics of the programme.

Types of data

There are four types of data that play a key role in both process and impact evaluations. These have been taken from chapter 7 of the Magenta Guide:

- administrative data collected specifically for the evaluation

- data managed by central government or donor agencies

- performance management or monitoring data already collected to support the administration of the programme

- new data needed to support the evaluation

An important step for evaluation is to consider what data is already available or is being collected for other purposes. Are there ways to make use of the data to save time and reduce the burden on staff members?

You must then consider what data will need to be collected specifically for the evaluation. What are the most appropriate means and methods of gathering information? Have you budgeted for collecting this data and do you have the resources you need? You will need to think about what you can spend on data collection and manage expectations about what you can do with the money and resources.

For new data collection there are many considerations to be made, highlighted in the box below. For more information refer to chapter 7 of Magenta Guide.

Data protection

Remember that you can’t just pull data from anywhere so you will need to investigate the impact of data sharing regulations. Whilst there are very few restrictions on sharing anonymised data, you may wish to match data from multiple sources or from multiple organisations which requires identifying information. This means you need to rely on a stated justification for collecting, sorting and sharing the data. Sometimes this means gaining specific consent from the data subjects themselves.

Data protection will vary across different countries. For countries in the European Union you will need to abide by the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). You can understand more about this by using the Information Commissioners Office (ICO) self-assessment toolkit.

There are differences around data protection worldwide. The UN have put together a list of the data protection and privacy legislation worldwide and these that you can view here.

Data collection - have you answered these questions?

|

Resources needed for evaluations

Any evaluation will require significant input to ensure it is designed and delivered successfully. This is true for both in house evaluations and those that are externally commissioned. The table below shows the types of resources that will be needed. This is a summary from the Magenta Guide by the UK Treasury. For more detailed information, read chapter 4.9. Whilst this is focused on the UK it is relevant for all audiences.

| Resources | What does this involve? |

|---|---|

| Financial | Most of the cost of the evaluation is likely to occur after implementation so this should be planned into the budget. Remember new data collection can be costly. |

| Management | Project management costs such as commissioning an evaluation, day to day activities, reacting to issues. |

| Analytical | Taking on specialists such as economists and statisticians to support the evaluation. |

| Delivery bodies | Engagement with those delivering the programme is crucial. They will need to know what input is required from them and how they will benefit from findings. |

| Dissemination | Reporting methods for findings, e.g. reports, case studies, presentation. |

| Wider stakeholders | The level of involvement with other stakeholders will be specific to the programme, but may include informing them about the evaluation, and inviting them to participate in research. |

| Peer review | In order to ensure quality, it may be necessary to have aspects of the evaluation peer reviewed. This may include the methodology, research tools, outputs including interim and final reports. |

Contracting an evaluation

Once you have considered the evaluation questions and the method, and thus understand the data and resources required, you will be able to think about how to approach your evaluation. Will you conduct the evaluation in house or will you need to commission it?

The resources section above highlights the skills and capacity that is necessary, including data collection and analysis, project management, IT etc. Self-evaluation can be useful to understand progress during the programme.

However, for impact bond evaluations the independence of evaluators is important as this gives the evaluation findings credibility, particularly with external stakeholders. Public service accountability is important and without a level of independence people may think that the evaluation is biased by commercial interests or to feed a government initiative. Independence and avoiding conflicts of interest are very important.

Invitation to tender

When pursuing an externally commissioned evaluation you will need to write an invitation to tender. Here is a summary of what information will need to be articulated in your invitation to tender document. This is taken from the Good Practice Guide

| Points | What should be included? |

|---|---|

| Background | Clear and concise description of activities being evaluated, including timescales, partner organisations and data available. |

| Scope | Boundaries outlining what will be evaluated. |

| Objectives | The articulation of your specific evaluation questions. |

| Methodology | Outline of the preferred methodologies (qualitative, quantitative, mixed methods) or evaluation activities (reflective learning events, practitioner workshops) |

| Dissemination | Reporting methods for findings, e.g. reports, case studies, presentation. |

| Deadlines | Deadlines for the submission of tender and reporting deadlines for each phase. |

| Deliverables | Statement of what is required, e.g. project planning meetings, evaluation framework, reports, results presentation. |

| Budget | If you know what you want you add a maximum budget, but if you are flexible you may ask for a range of options from evaluators. |

| Contracting | Terms and conditions to purchase research services, e.g. confidentiality, data sharing, intellectual property |

| Supporting documents | Optional inclusion of things like your business plan, information about the stakeholder group, or the commissioning approach. |

| Instructions on tendering | Be clear how you want tenders submitted. Must include contact information, 1-2 page summary of proposal, interpretation of brief, proposed methodology, timetable, quality assurance, cost. |

The Good Practice Guide also offers guidance into the procurement process, how to select an evaluator and arranging meet ups with them. This is beyond the scope of this technical guide but is useful if this is the first time you have commissioned an evaluation.

Publishing your evaluation

Making your evaluation public will enable you to share the benefits of evaluating your impact bond, share different approaches and highlight the challenges. You may choose to publish your evaluation so it can be both an internal resource and useful for others wanting to know the evidence base around the relevant policy area or on the effectiveness of the impact bond mechanism, or for others who may wish to conduct an evaluation. You can host this online, such as on your own website, a government or donor agency website, or on the evaluator’s site. You can also publish this in the GO Lab's publications library - get in touch if you would like to do this.

What does ‘good’ look like?

5 minute read

There is no template for a ‘good’ evaluation. It is also important to note that a good evaluation does not mean there will always be good outcomes. Rather, it will provide clear answers to the research questions and give you insights into the programme that you wanted when setting out your evaluation strategy.

Good evaluations will have a robust methodology, focused research questions, high quality data, excellent project management and engagement between stakeholders. This chapter will highlight three evaluations of impact bonds around the world. The first two are examples of evaluations of the intervention and the third is an evaluation of the impact bond mechanism. View our case studies for more examples.

India – Educate Girls

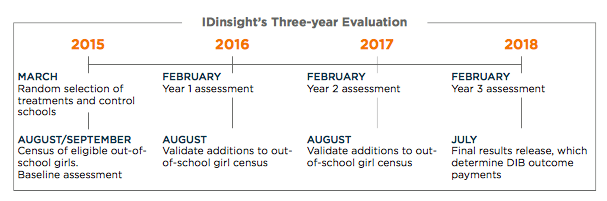

Educate Girls is a charity in India that launched a development impact bond (DIB) in Rajasthan in September 2015. They sought to address educational inequalities by encouraging families to send their children to school and improve the quality of teaching. This information is taken from the Final Evaluation Report.

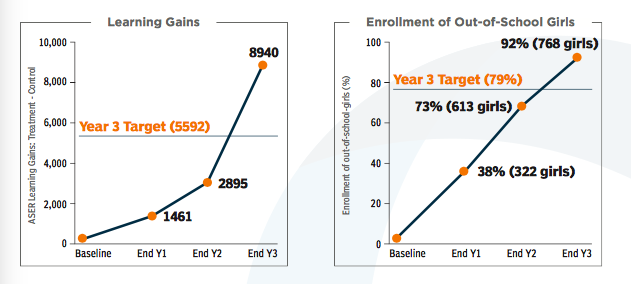

IDinsight designed and conducted a three-year impact evaluation of Educate Girls’s programme. They measured two outcomes: learning gains of boys and girls in grades 3-5 and enrolment of out of school girls.

Outcome 1 - Learning gains

80% of the final payment for the DIB were for learning gains. They were measured in a randomised control trial. The evaluation included a sample ~ 12,000 students in grades 3-5 across 332 schools in 282 villages. Half the villages were randomly assigned to receive the Educate Girls programme while the other half formed the control group (the counterfactual).

IDinsight used the Annual Status of Education Report (ASER) testing tool to assess the student’s maths and literacy. A baseline was taken at the beginning of the intervention, and another assessment was taken at the end of the third school year. The difference between a child’s learning level at baseline and their final assessment represented the amount of learning gained. The students who had been on the programme were compared to the control group to show the impact of the programme.

Outcome 2 – Enrolment

The other 20% of payments was for enrolment. At the beginning, Educate Girls compiled a list of all out of school girls aged 7-14. At the end of each year, Educate Girls reported successful enrolment and these were verified by IDinsight. Causal effect of the programme was not possible because project partners decided it would cost too much to do a census of all households.

Final results

Educate Girls surpassed its three year targets for both outcomes. With slow progress early on, by the third year there were massive increases, which drove them to exceed the final target for learning gains by 60%.

UK - Peterborough ‘ONE’ Service

The One Service was a social impact bond that operated at Peterborough Prison between 2010 and 2015. The programme offered support to adult male offenders released from the prison with the aim of reducing reoffending.

Research questions

The evaluation of the programme was commissioned by the Ministry of Justice (MoJ) in 2010. There were five research questions, summarised as:

- How did the pilot lead to better outcomes of reduced reoffending?

- What wider costs and benefits were incurred through the SIB?

- To what extent did stakeholders feel that the SIB led to greater innovation and efficiency?

- What were the strengths and weaknesses of the SIB model?

- What key messages can be taken from the SIB for the future?

Research approach

The MoJ conducted a process evaluation using mainly qualitative methods in order to understand how the One Service operated. Separately, independent assessors measured the impact of the service. The target required for outcome payments to be made was 7.5%.

The report was based on interviews with 29 stakeholders involved, 15 offenders and a review of the case files of 15 service users

Findings

You can view all the findings in the final evaluation report. To summarise against the research questions (stated above),

- Virtually all service users were positive about the experience and the support they received

- Wider benefits included more services provided that were developed through the One Service, other agencies have adopted some elements of the One Service, and stakeholders did not report major costs or disadvantages from the pilot

- The One Service was innovative as it was the first SIB and it delivered a new service and filled a gap in provision. However, this does not mean that the intervention itself was innovative.

- Strengths included the model as the providers did not bear outcome risk that was dependent on the results

- The initiative was the first of its kind and the conclusions and lessons were relevant for future SIBs and reoffending programmes.

DIB pilot programme – ICRC, Village Enterprise, Quality Education India

The purpose of the evaluation was to generate learnings and recommendations on the use of DIBs as an instrument for aid delivery, by using the experience of the DFID DIB pilot programme to inform future policy. The evaluation also aimed to help DFID and project partners evaluate whether the tools they are developing are useful scalable and replicable.

The three projects under the pilot programme were:

- International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) Humanitarian impact bond for physical rehabilitation

- Village enterprise -microenterprise poverty graduation Impact bond

- Support to British Asian Trust to design impact bonds for education and other outcomes in South Asia

Research approach

The evaluation focuses specifically on the effect of the DIB mechanism. IN order to isolate the ‘DIB effect’ from another type of aid funding mechanism, the evaluation uses a combination of process tracing (a qualitative research method that looks for the causal chain that leads to outcomes) and comparative analysis. A cost effectiveness analysis was also undertaken.

Evaluation framework

There were two evaluation questions:

- Assess two the DIB model affects the design, delivery, performance and effectiveness of development interventions

- What improvements can be made to the process of designing and agreeing DIBs to increase the model’s benefits and reduce the associated transaction costs?

There was a range of sub-questions and they were mapped to the DAC criteria, and DIB-effect indicators. These set out what the evaluation team needed to measure the effects resulting from the use of the DIB model. You can view the full evaluation framework in the evaluation report.

The cost effectiveness analysis was guided by the 4Es framework which is a measurement of Economy, Efficiency, Effectiveness and Equity.

Evaluation outputs

Four evaluation reports will be published to share findings. Each one will build upon the previous report, highlighting continuities, new areas for development and additional outcomes achieved or areas of concern.

To find out more about this, read the Independent Evaluation of Development Impact Bonds (DIBs Pilot Programme)

Acknowledgements

Grace Young, Policy and Communications Officer, was the writer and editor of this guide. Many members of the GO Lab team helped where their expertise was useful, including Eleanor Carter, Research Director and Andreea Anastasiu, Senior Engagement Officer. We are also grateful to James Ronicle, Associate Director at Ecorys who reviewed this guide before it was published.

We have designated this and other guides as ‘beta’ documents and we warmly welcome any comments or suggestions. We will regularly review and update our material in response. Please email your feedback to golab@bsg.ox.ac.uk.