Pricing outcomes

This guide will help outcome payers in an outcomes-based contract decide how much to pay for an outcome, understand the decisions to be made and offer examples.

Overview

2 minute read

In an outcomes-based contract, either part or all of payment to the provider (and in some cases, an investor) is linked to the achievement of specified outcomes. As a result, the price that is paid for particular outcomes is important to ensuring the contract is successful. Outcome payers should engage with all parties throughout the price development process, to strike a balance between the value to the outcome payer, the cost of delivering the service to providers and the distribution of financial risk.

The parameters for price setting

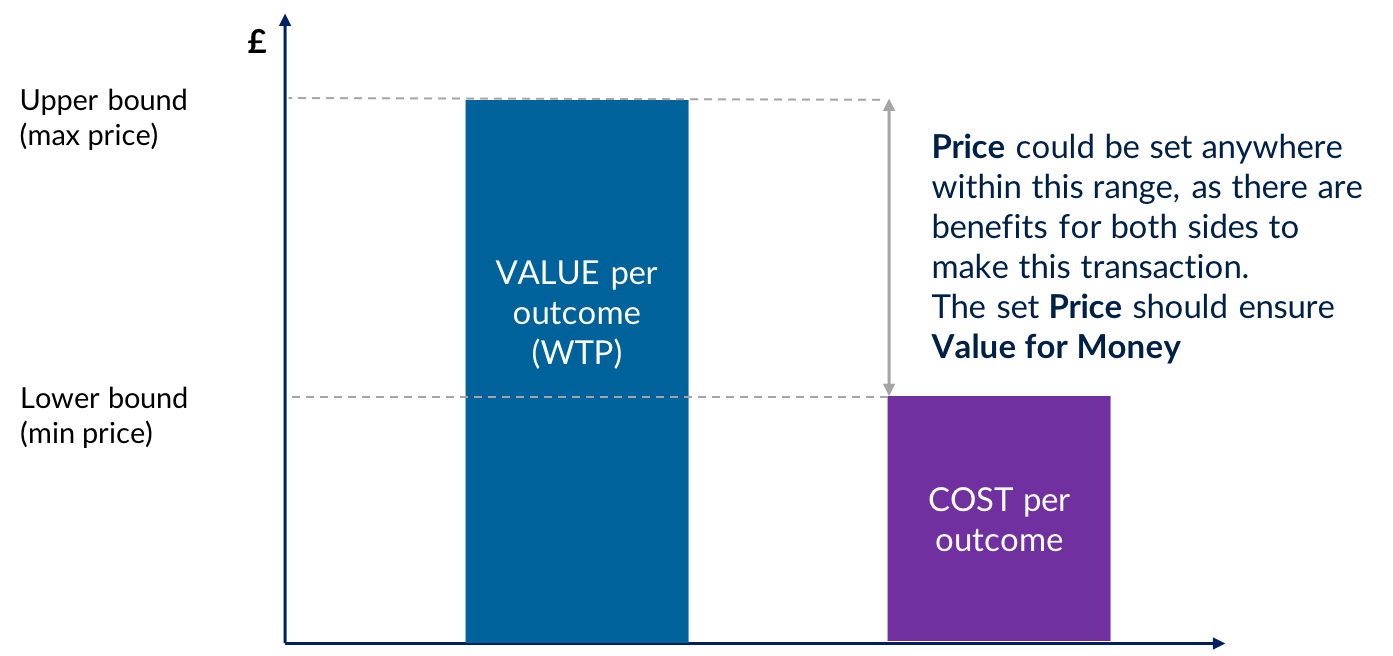

Ideally, pricing outcomes involves first deriving the value to set the upper bound, then estimating the cost to set the lower bound, before finally setting the most efficient price within the range between value and cost.

Value represents the maximum amount of money the outcome payer is prepared to pay for a good/service.

The value of a particular outcome will vary based on who is paying for it, and depends on a range of financial, political, social and economic considerations. It includes the intrinsic value, comprising all of the long-term benefits of individuals achieving the outcome, and the prevented costs, the fiscal benefits of preventing costly social problems.

Cost is the cost of delivery, development, management and financing to the service provider (and where applicable, investor).

An outcome payer can attempt to estimate the cost in a number of ways. These include engaging with the market, examining the historical costs of the service if it has been delivered previously, or – if it has not - comparison to similar services which are likely to use similar resources.

Price is the amount to be paid for the good/service agreed between the provider and outcome payer.

If there are many potential providers, the price can be set by working downwards from the value, where providers bid at a discount against a maximum price. If the contract is developed with a single provider, the price can be set by working upwards from the cost, negotiating a price that reflects the distribution of risk between parties.

Factors which affect the price

Cohort specification

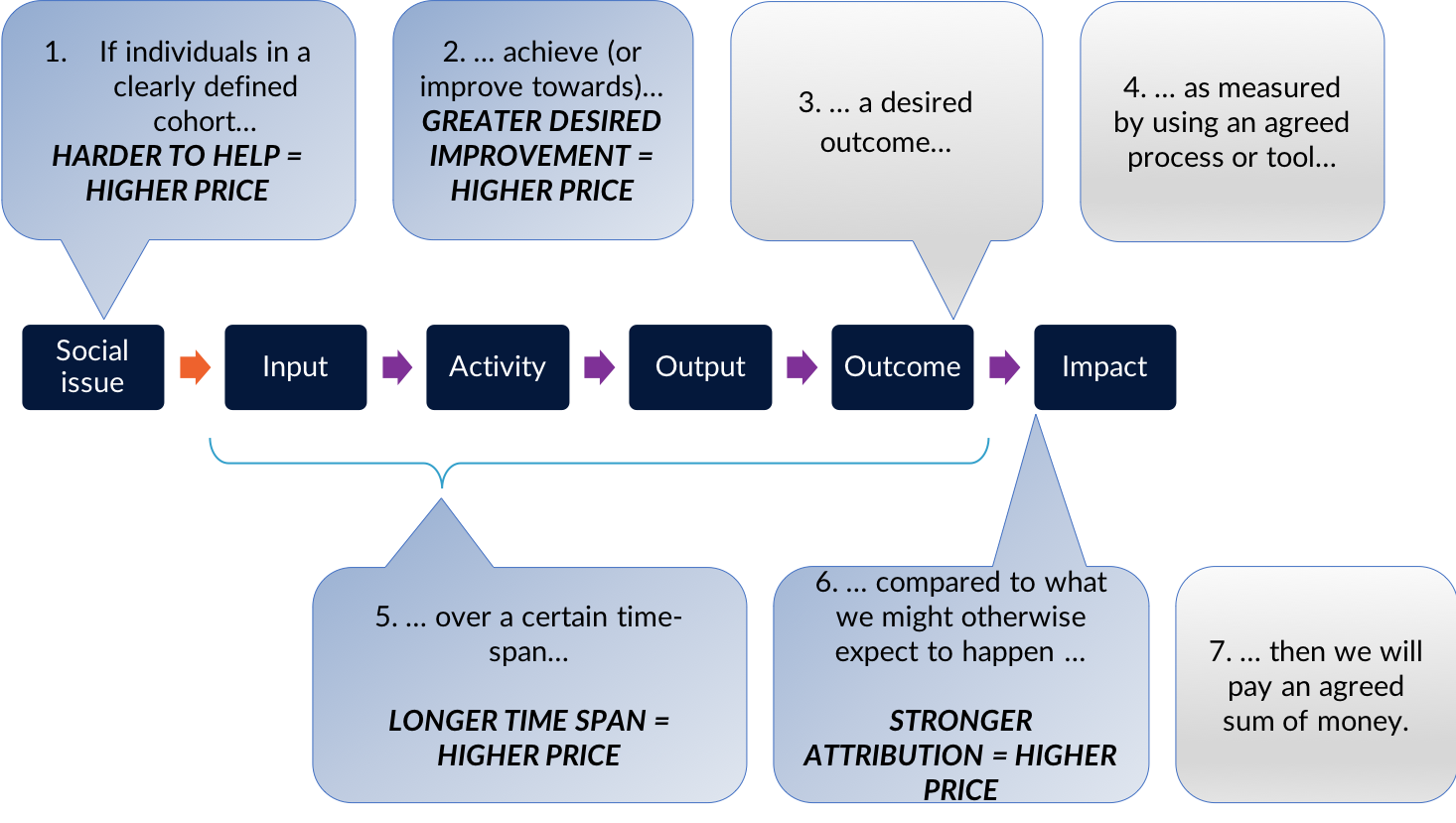

Cohorts that are harder to help will require more support, resulting in higher costs for the provider, and therefore a higher price. Cohorts with diverse needs require more complex pricing structures, and may be susceptible to perverse incentives.

Level of improvement

The greater the level of improvement required for service users to reach desired outcomes, the more intensive support they will require, resulting in a higher price.

Likelihood of success

If there is more uncertainty about whether outcomes will be achieved, there is more risk to the provider/investor. To compensate for this, they may expect a higher price.

Timing of payment

Later payments for outcomes are more likely to reflect long-term policy goals, but increase financing costs and uncertainty for the provider, requiring a higher price. In contrast, earlier payments can reduce financing costs and lower uncertainty, leading to a reduced price, but potentially fail to deliver long-term goals.

Additionality

Ideally, payment should only be made for outcomes over and above what would have happened anyway. If it is believed some outcomes would have happened without the provider’s intervention, the price should be reduced accordingly.

Budgetary constraints

If an outcomes-based contract is particularly successful, the outcome payer may have to pay out more than expected. This can be mitigated by defining payment caps - either on the total payment to providers, or on the total payable outcome per individual.

Introduction

5 minute read

1.1 Payment mechanism

An outcomes-based contract (OBC) involves the provider’s charges being linked, in whole or part, to the achievement of defined business outcomes for the customer, rather than being based on input costs, such as labour, or outputs, such as transaction volumes. For instance, a contract for the provision of training to support unemployed people into work may have payments linked to the proportion of trained individuals that find employment and maintain it for a minimum period.

An OBC can be underpinned by an impact bond (IB), where a third party investor provides up-front working capital to fund provision prior to outcome payments being made, and takes on the risk of non-payment if outcomes are not achieved. This relatively new type of financing method has been used in countries across the world. IBs originated in the UK which as of mid-2019 has the greatest number globally. They are in line with approach taken by the World Bank Group’s Maximising Finance for Development. They have been adopted in a number of countries to address a range of problems including supporting children at risk of being taken into care, tackling homelessness, improving health outcomes, reducing offending and a range of other social issues.

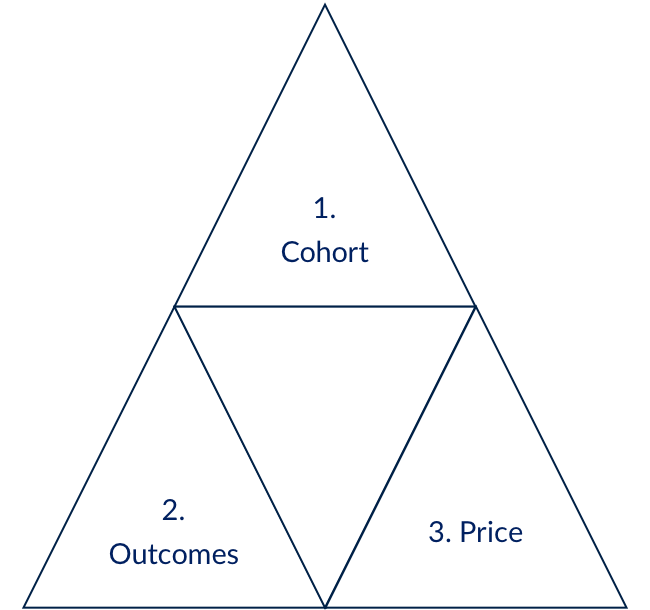

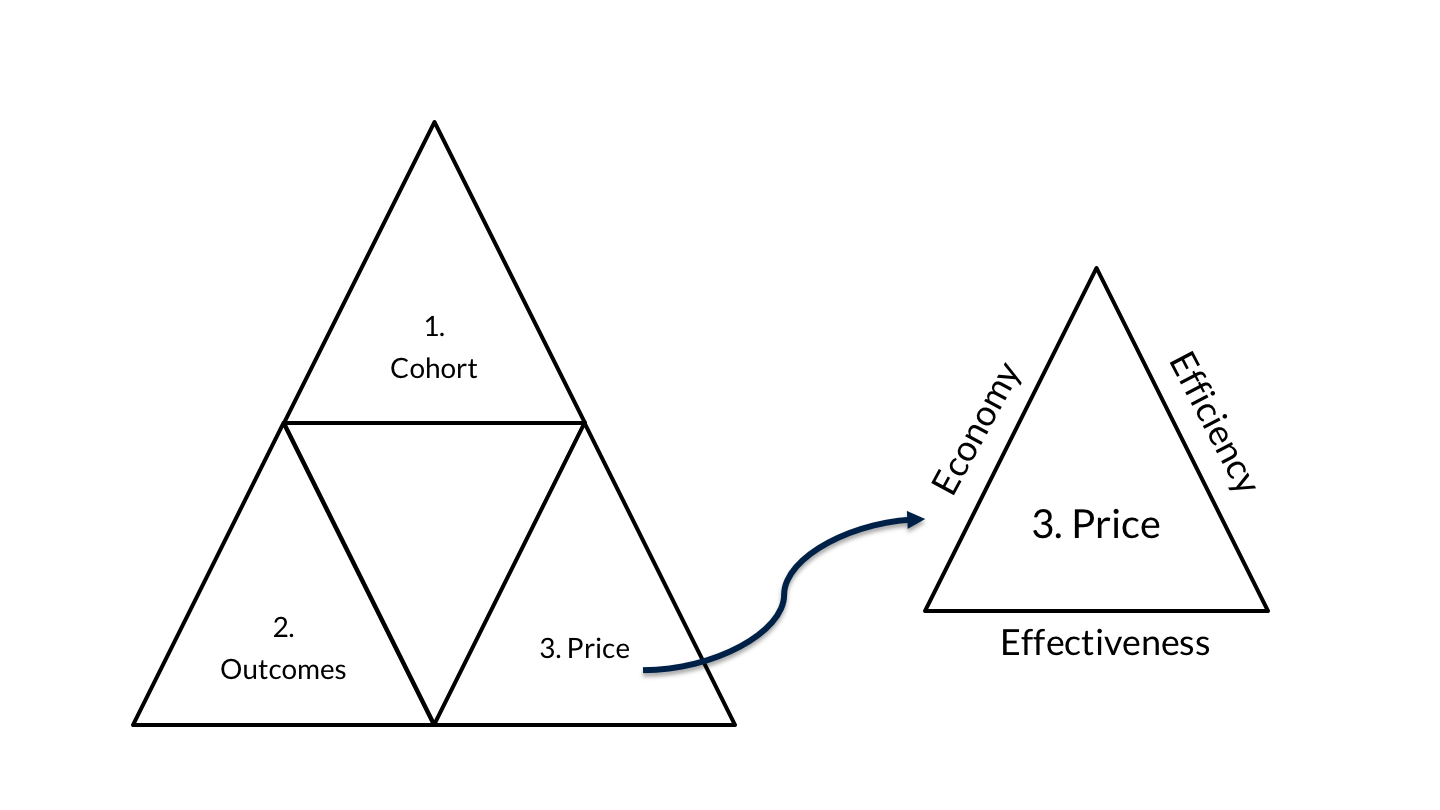

The idea is simple and powerful, but it requires a clear definition of who is affected by the social issue you aim to address (the cohort), what ‘good’ looks like for those people (the outcomes), and how much to pay if that is achieved (the price). These three considerations – cohort, outcomes and price – are all inter-related. Changing one will affect at least one of the others.

Approaches to defining the cohort and choosing which outcomes to pay for are examined in our guide to Setting and Measuring Outcomes. They are equally important in circumstances where it is desirable to measure outcomes, but the funder or buyer of the service does not want to move immediately to outcomes-based payment. However, in this guide we aim to create a framework to support an outcome payer who wants to pay, in part or in full, for the outcomes achieved.

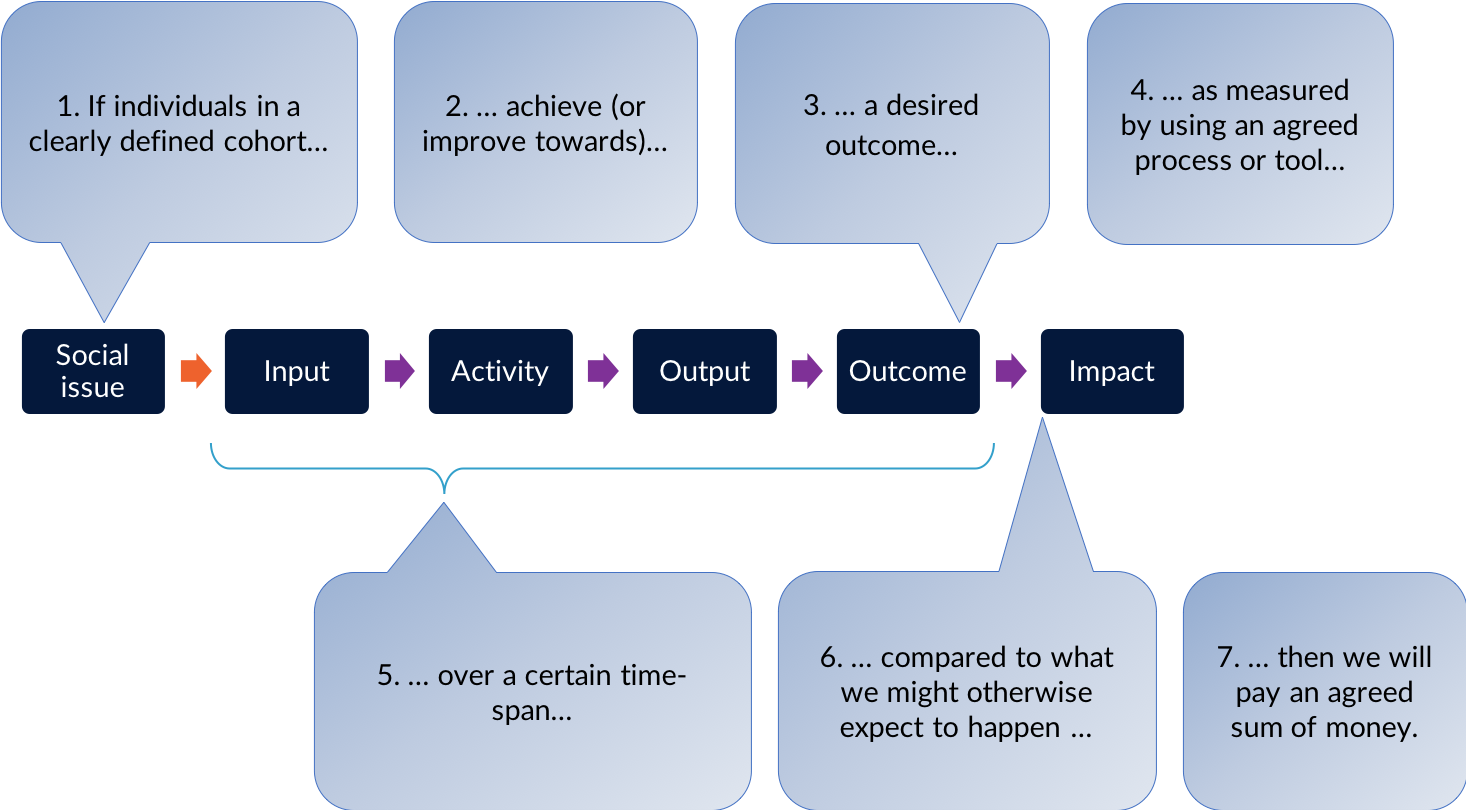

The basic ingredients underpinning a payment mechanism may be summarised in the following sentence:

“If individuals in a clearly defined cohort achieve (or improve towards) a desired outcome, as measured by using an agreed process or tool, over a certain time span, compared to what we might expect to happen otherwise, then an outcome payer will pay an agreed amount of money.”

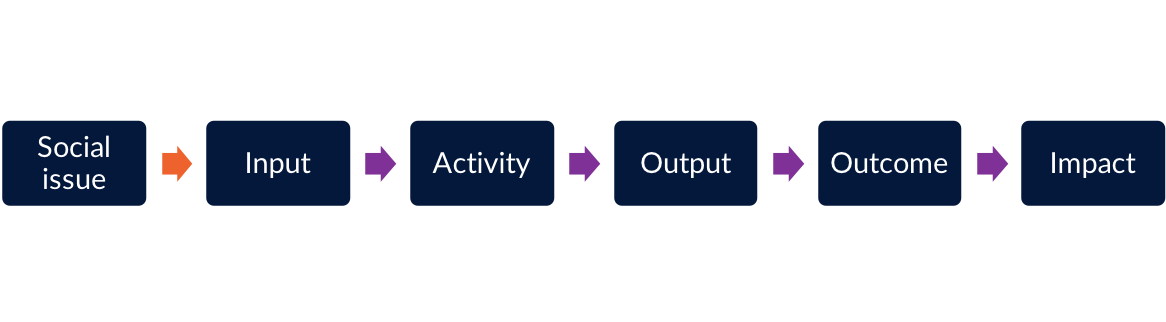

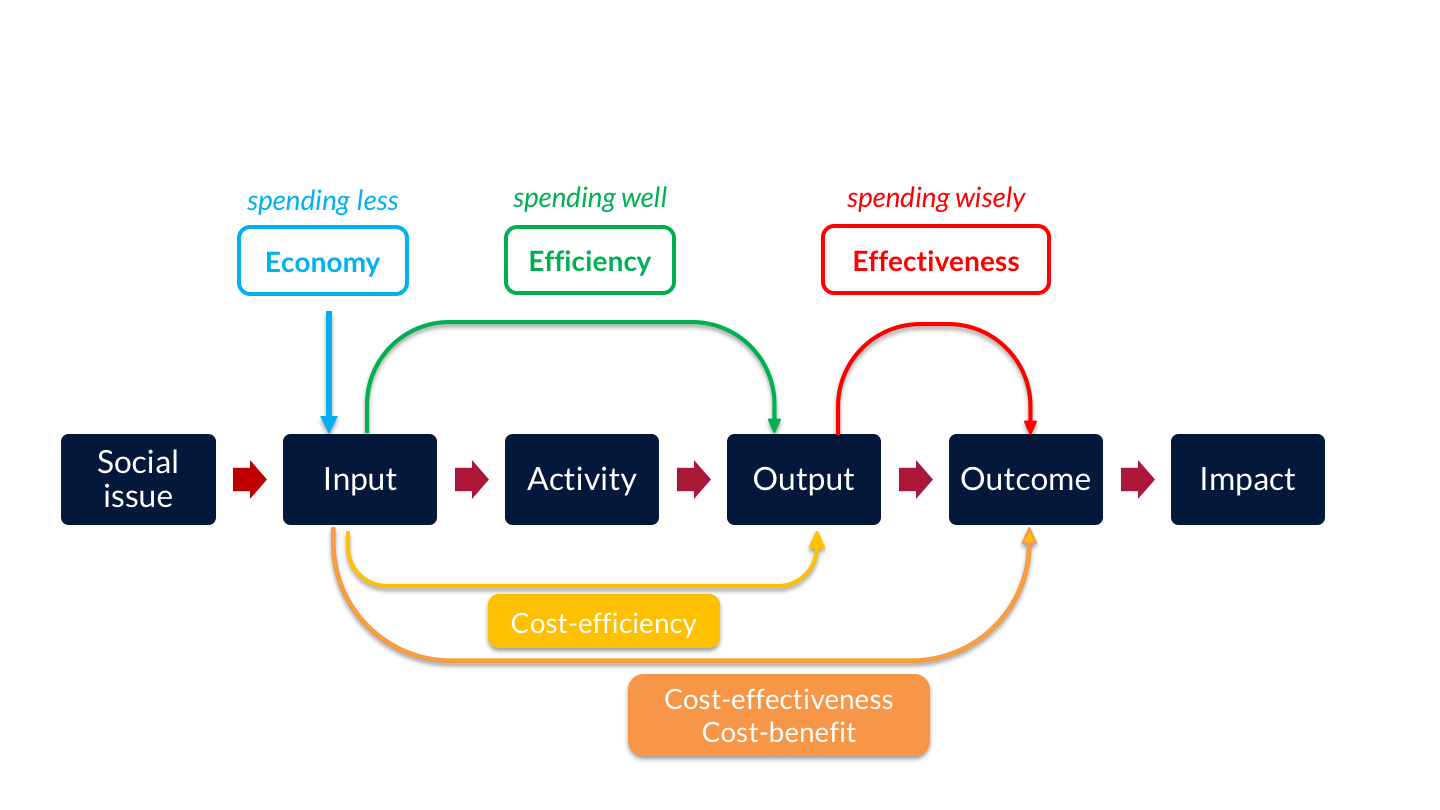

A theory of change, or logic model, can be a useful tool to describe the social issue you are considering and how people may benefit from the service or ‘intervention’ the provider(s) will deliver. A theory of change describes how ‘inputs’ (i.e. resources such as money and staff time) are used to deliver ‘activities’ (e.g. recruiting participants and setting up a mentoring scheme), which produce outputs (e.g. beneficiaries participating in the mentoring scheme), which will lead to desired outcomes (e.g. improved engagement at school) and impact (e.g. better education results and life prospects). The theory of change tool is useful in the processes of setting and measuring outcomes and evaluating outcomes-based contracts. While it relies on a much simplified version of the messy reality of improving outcomes for people, it remains a popular approach.

Figure 1.3 shows how the basic ingredients underpinning a payment mechanism map against a basic “theory of change”.

1.2 Pricing outcomes within the payment mechanism

The payment mechanism is an important aspect of the contract that will influence how the outcome payer(s) manage the relationship with the delivery organisation and other stakeholders, and monitor progress.

It is worth noting that it is not the only tool that should be used in order to effectively manage your outcomes-based contract. It is important to distinguish between:

- Minimum service standards, which you will specify in the contract and use to hold the provider to account for – e.g. safeguarding procedures.

- Reporting requirements, which you will use to monitor the progress of the intervention, and to discuss ways to overcome unexpected challenges with other stakeholders and build a culture of ongoing learning. These metrics may monitor progress and impact both before a set key payment trigger and beyond the payment.

- Defining the cohort and desired outcomes, and working out how to measure them

- Putting a price on outcomes which are to be paid for, which are the focus of this document.

You may wish to consider a payment structure that combines elements of a ‘fee-for-service’ contract and elements of an ‘outcome based’ contract. For instance, you may agree initial payments for outputs or activities (such as engagement and assessment) and later incentivisation payments subjects to the achievement of desired, longer term outcomes.

1.3 Using an engaged approach

For an outcomes-based contract to work effectively it needs to strike a balance between what is valuable to the outcome payer and what is possible from a service delivery perspective, and acceptable from a financial risk perspective. That is why it is important for outcome payers to engage with providers and (in the case of impact bonds) investors throughout the process, from start to end. A fundamental purpose of using an outcomes-based contract and SIBs is to generate a shared understanding between an outcome payer and providers of ‘what good looks like’, i.e. the desired outcomes, and to allow more autonomy for the provider to use their skills in bringing about the desired outcomes. Although defining the aspects of a payment mechanism will, by necessity, seem like ‘technical’ work, remember that the contract and the payment mechanism should strengthen and not weaken the relationship between outcome payer and provider.

For this reason, often outcome payers see a benefit in treating the contract more as a partnership than a transactional relationship. As this guide will show, there are many aspects of pricing the outcome where feedback from the market is helpful, or even essential. There will of course be limitations around how much providers and investors can share and some information might be commercially sensitive. An outcome payer should be clear upfront as to how the information shared will be used, and agree terms of sharing information with all those engaged. A partnership approach (especially if it is to work in the long-term) requires trust and transparency, and relies on parties conducting the negotiations in a spirit of openness and honesty.

An outcome payer should be prepared to allow room for revisions (prior to procurement) and negotiations (as part of the procurement process to appoint provider(s) and/or investor(s). It is important to allow sufficient time throughout the project development process for these conversations to take place. An outcome payer might find it helpful to set the right expectations within their own organisation around (i) the timeframes for completing the work, (ii) the need to have some flexibility in the negotiations with the provider(s) and investor(s) and (iii) the fact that numbers are indicative in the early stages and subject to change during procurement negotiations.

In the process of pricing outcomes, it can be very helpful to discuss with others who have faced similar questions. The GO Lab has a range of activity that supports peer learning, including regional workshops and events, as well as the impact bond knowledge club.

The parameters for price setting

18 minute read

2.1 Steps in price setting

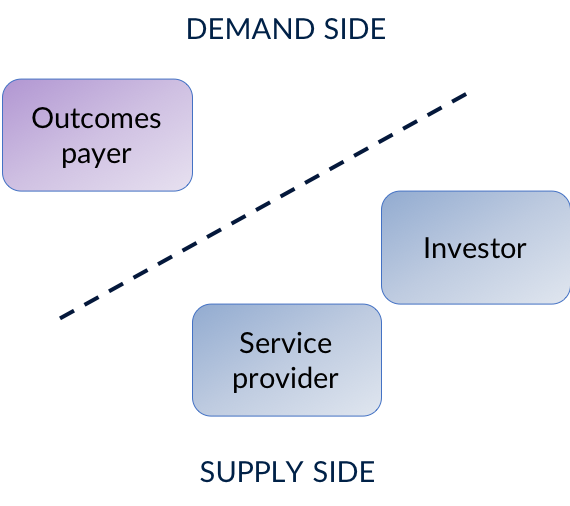

The fundamental economic concept of supply and demand is important to the pricing approach. The demand side contains the customers who have a willingness to pay up to a certain amount to acquire a good or service. The supply side is represented by the providers who are willing to sell their good or service for an amount greater than (or equal to) the cost of producing it. In an outcomes-based contract, the outcome payer (e.g. the funder or commissioner) represents the demand side, and the supply side is represented by the provider. In an impact bond model, the investor usually joins the supply side (see our guide to awarding an outcomes-based contract for more on how impact bonds are structured).

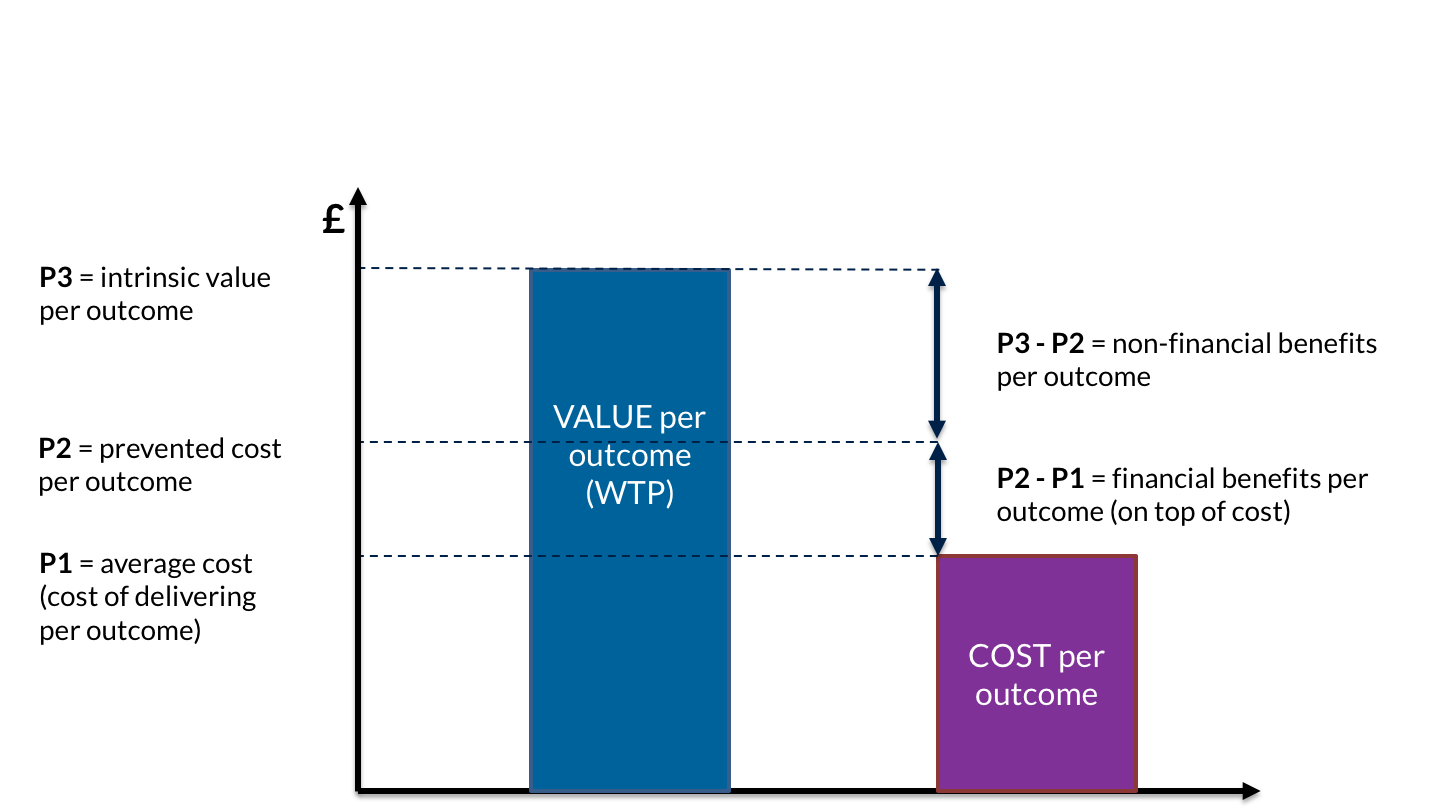

- Value represents the maximum amount of money the demand side is prepared to pay for a good or service (the ‘willingness to pay’ or WTP). In this case, value is ascertained from the perspective of the outcome payer.

- Cost is ascertained from the provider’s perspective, and includes not only the cost of delivery, but also development, management and financing costs. As we will explain, outcomes-based contracts always have financing costs, which will vary according to the perceived level of risk of achieving the required outcomes, and the length of time before outcomes are paid.

- Price is the amount of money to be paid for the good or service. In an outcomes-based contract, there can be a price for each outcome, and a price for the outcomes in total, agreed between the provider and the outcomes payer.

If the price is lower than the value, the outcomes payer benefits from the transaction. If the price is higher than the cost, then the provider benefits from the transaction. Therefore, ideally a transaction only takes place when the value is greater than (or equal) to the price and price greater than the cost. Figure 2.2. shows this graphically.

- Derive the Value. This sets the upper boundary (i.e. the maximum price) of either total payment, or payment per outcome, by estimating the ‘economic value’ of the outcome

- Estimate the Cost. This sets the lower boundary (i.e. the minimum price), by determining the costs to the provider of delivering the service.

- Set the Price. This sets the most efficient price within the range between value and cost. There are different considerations to ensure value for money.

If it is not practical to both derive the value and estimate the cost, it is possible to set the price by either working downwards from the value, or upwards from the cost, as explained in 2.4 how to set the price.

2.2 Derive the value

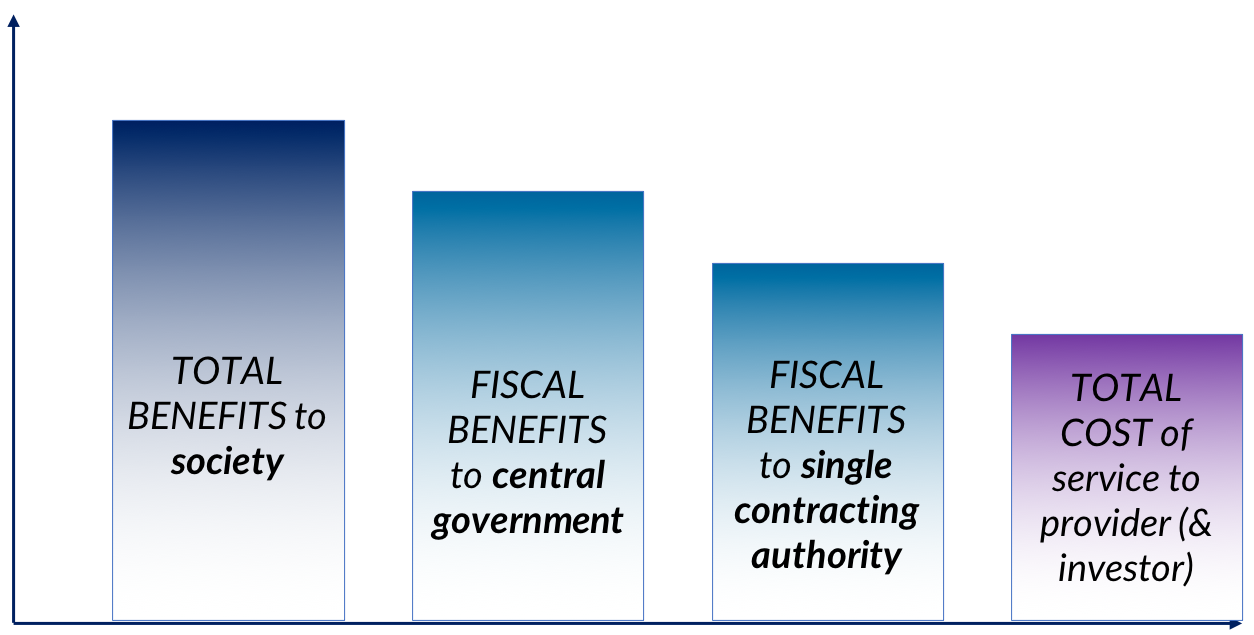

Deriving the value allows the setting of an upper-bound to what can be paid. Value can be subjective: not only might value of an outcome vary according to who is paying for the outcomes, but there may also be different perspectives within a governing body or outcome payer, and also across time. In short, value is in the eye of the beholder, and is dependent on a range of financial, political, social and economic considerations, which vary according to the organisation or body concerned.

As an example of a national government’s finance ministry perspective, on defining the value in the UK public sector, the HM Treasury's Green Book addresses the ‘Scope of Benefits’ concept by grouping benefits with respect to their scope into three sections: (i) Direct public sector benefits (to originating organisation); (ii) Indirect public sector benefits (to other public sector organisations); (iii) Wider benefits to society (e.g. households, individuals, businesses).

This kind of national perspective can be very important when a central government is the outcomes payer, or is supporting others to pay for outcomes.

However, most outcomes payers have to look at the value of outcomes from a much narrower perspective. If there is a private outcome payer, local and regional government, or single central government department, they are more likely to consider:

- fiscal benefits i.e. savings in their own budget;

- the fulfilment of their responsibilities and duties;

- their political and/or social priorities.

It is usually hard, for example, for an education department to pay for reduced offending outcomes, or for a health department to pay for reduced homelessness, even though those benefits could well occur as a result of work those departments paid for.

This is one of the reasons why some countries have set up outcomes funds. Government as a whole can support projects which produce wider societal benefits, which an individual department or regional / local government cannot afford to fund.

Depending on the circumstances, defining the value may not always be possible or useful. Where this is the case, you might wish to refer to 2.3 estimating the costs.

However, it may be helpful to put a figure on the value for two reasons:

- There is a reason to understand the overall economic benefit of individuals achieving certain outcomes, for example to make the case for new spending, or for collaboration between multiple departments.

- The business case relies on unlocking future budget savings to particular departments or sub-national governments as a result of individuals achieving certain outcomes.

2.2.1 Intrinsic value

The intrinsic value of an outcome is an attempt to put a monetary figure on all the long-term benefits that might occur for society when an individual achieves particular outcomes. It goes beyond direct fiscal benefits to the outcomes payer. Often, this value is defined in moral and political terms – it is the reason why we educate children, rehabilitate offenders, help rough sleepers, and so on. But especially in the case of national government, it is possible to attempt to quantify the value using Cost-Benefit Analysis (CBA). CBA is widely used across governments to appraise spending options. It attempts to calculate the value to society of achieving the outcome. Most governments will have an approved approach to CBA so we do not cover in detail in here. For example, the UK has CBA guidance for local partnerships. This gives a word of caution, though: “CBA is not an exact science and its outputs are a guide to decision-making, not a substitute for thought’’.

2.2.2 Prevented Costs

Calculating prevented cost is an attempt to calculate the fiscal benefits that might occur when an individual or group achieves particular outcomes. This approach focuses on how the achievement of certain outcomes now might reduce costs to the outcome payer in the future. It uses a similar form of analysis to the ‘intrinsic value’ approach, but with a narrower focus.

Preventing costly social problems from arising in the first place, or reducing their incidence, is often likely to lead both to better social outcomes for people and lower public sector spending.

However, it is difficult to allocate resources to preventative activities when there are budget pressures, and the available funding often has to be prioritised towards people in need of urgent care to be supported first. Furthermore, the difficulty of knowing for sure whether the preventative activities will actually deliver their demand reduction promises, challenges the ability to invest in long-term preventative activities.

An outcome-based contract may help enable a focus on preventative activities that will lead to better future outcomes, and reduced demand (and therefore costs). It also has the potential to enable ‘double running’ of budgets, where preventative and remedial work is run in parallel, provided the demand reduction unlocked by the preventative work is able to generate genuine future budgetary savings.

2.2.3 How to calculate the value

Whether you are seeking to calculate intrinsic value or prevented costs, the approach is similar.

Most importantly, as mentioned at the start of this guide, it is important to have a clear understanding of the cohort or group of people for whom better outcomes are targeted. You can read more about this in our guide to Setting and Measuring Outcomes.

You should then start to think about all the benefits arising from the achievement of a certain outcome. If you are seeking to calculate the overall intrinsic value, you will need to consider them all. But if you are seeking to calculate prevented costs to a particular department or sub-national government, who will also be the outcome payer, you probably just need to focus on the first two: cohort member and outcome payer.

- The cohort member – what has changed for them as a result of the outcome? Is it immediate, or will it impact something in the future? How long will the impact last for them?

- The outcome payer – what is the impact on your organisation as a result of the outcome? Does it increase or reduce your spending now, or will it affect it in the future?

- The public sector – are there other impacts elsewhere in the public sector (to other local or central government bodies)? How does it impact upon their service provision or spending?

- Wider benefits to society – are other individuals impacted? Do non-public sector organisations (e.g. local businesses) benefit? Are there any wider impacts on the local community or area?

Your aim is to quantify, each of these benefits as well as being able to describe what the impact looks like. Sourcing this information can be difficult; ideally the scope and scale of these benefits will come from research done on the cohort you are aiming to target. It is advised to follow a conservative and evidence-based approach to pre-empt future criticism when discussing with other partners.

In some cases either an outcome payer or service providers might be able to provide data or feedback on the types and/or quantity of benefit. Alternatively, you may need to rely on published research for similar cohorts.

These benefits will fall into two broad categories: Fiscal benefits and economic/social benefits. Fiscal benefit sare impacts on the public sector budget which are either ‘cashable’(where expenditure released from the change in outcomes is freed up and can be reallocated elsewhere, e.g. no longer needing to spot-purchase residential children’s care) or ‘non-cashable’ (which represent a benefit to the public from freeing up resources even if public expenditure is not reduced, e.g.. reduced demand from frequent attenders in A&E allows staff to concentrate on more critical cases). Economic/social benefits not only consist of such benefits, but also wider gains to society that are often harder to identify and value in monetary terms.

- Fiscal benefits (both cashable and non-cashable) can be estimated using cost to the public sector organisation responsible for delivery. Ideally you will be able to calculate these using data collected within local public sector organisations. Some jurisdictions may have nationally used unit costs – for example, the UK has the Health and Social Care Unit Cost database published by PRRSU or The New Economy Unit Cost database.

- Economic/Social benefits includes fiscal benefits and more. Those other benefits are often harder to monetise and economists will use a range of techniques to estimate them. You will need to do some research to ensure you are using values relevant to your outcome and cohort. Again, there may be some useful national ‘collections’ of these values: for example, the UK has the New Economy Unit Cost database referenced above, and the National TOMS Framework, and there is guidance in Chapter 6 of the Green Book.

There are some benefits for which it is either unfeasible, or undesirable, to derive monetary values for – such as greater wellbeing. These should still be considered alongside those in monetary terms, in order to decide if your actual ‘willingness to pay’ is higher than the final monetary figure.

Where a program is commissioned on the basis of prevented costs, then unlike in the intrinsic value approach where a degree of estimation of the benefits of outcomes being achieved is permissible, it is important to be as precise as possible about the fiscal benefits to the outcomes payer and when these will occur. The outcomes payer is agreeing to pay for outcomes directly as a result of the savings that they expect to make, which will often actually finance those outcomes payments. Therefore, the focus will be on the “cashable” savings.

It can sometimes be quite straightforward to determine the cashable savings of a programme. For example a programme might be intended to reduce the number of children who have to be placed in the care of the state. If that care provision is paid for on a spot purchase basis at a known cost, and by the same agency that intends to pay for outcomes in a proposed outcomes-based contract, then there is a known direct saving to the outcomes payer if the number of children who go into care is reduced.

In other cases, though, it is much more difficult to determine cashable savings.

This may be because for example:

- The savings are hard to cash e.g. reducing the number of people who are sent to prison only saves prison costs if prisons can be partly or wholly closed down. If existing prisons are merely rendered less overcrowded, then, although this may deliver some intrinsic value (such as more productive ex-offenders) and non-cashable savings (such as more capacity in the prison system), prevented costs are likely to be much lower.

- Some of the savings may have been realised anyway and cannot easily be attributed to the program, e.g. if there is reduced offending amongst the cohort against a wider trend of falling crime which may account for some of the reduction.

- The savings occur too far in the future e.g. a program may reduce hospital admissions over the next five years, but the outcomes payer only has the flexibility to pay for outcomes which deliver savings within one year.

- Savings may go to organisations other than the outcomes payer e.g. a mental health programme for disadvantaged young people paid for by a school may help to reduce the chance of future offending, but the reduction in offending does not save that school any money.

2.2.4 Limitations in calculating value

Once the analysis of value is complete, you should reflect on these figures to decide the total value of the outcomes, and this total should represent the upper limit of public sector’s ‘willingness to pay’ for achieving that outcome (although in reality it is unlikely the analysis has been able to capture and monetise all the benefits).

If you are one of many public sector organisations identified in the analysis, you may wish to price an outcome based only on your own fiscal benefits. Alternatively, you may wish to use the analysis to engage other public sector outcome payers in order to price the outcome in accordance with realised benefits for them.

Proper analysis of the direct and wider impacts of outcomes can help to justify or reject the use of particular outcomes for payment, and provide a rigorous basis for a decision on expenditure by an outcomes payer. It can also help construct the case for co-commissioning or facilitating cross-agency working. For example, this approach can be useful for contracts which aim to meet the needs of individuals who move through different existing services which do not work well for them under the status quo. It can also provide a starting point if a service is completely new.

On the other hand, it can be difficult for teams with little or no analytical resource to make use of the tools of cost benefit analysis. Furthermore, if the analysis has not used local data, but relies on standard datasets, it may undermine trust in the resulting figures.

Depending on the issue being addressed, the time delay between the intervention and the achievement of medium to long term outcomes which are of most value to the outcome payer may make an outcome based contract unfeasible for a provider and/or social investor.

There can also be a problem in this approach with "prevalence”: the number of people in the target group who display (or might go on to display) the undesirable results which the intervention is intended to mitigate (or avoid).

There can also be a problem with “deadweight” which is the term often used for those who would have achieved a positive outcome even without the intervention.

The issues of timing of payments, prevalence and deadweight are all discussed further in Chapter 3.

Where a precise calculation of value cannot be carried out, it is possible to commission services through an outcome based contract using an estimated value derived from limited data.

It may then be possible to run an evaluation which makes a more robust assessment of the range of benefits which are delivered. For example, an IB designed to reduce rough sleeping might tie payment only to that – but the price paid may also have factored in expected reductions in crime and health service costs. A robust evaluation can show if these were achieved as expected, and therefore whether the price paid was justifiable, and further commissioning is warranted.

| Intrinsic value | Prevented Costs | |

|---|---|---|

| Key concept | Government’s ‘willingness to pay’ for a social outcome | Potential future budgetary savings |

| When helpful? | When value of an outcome is not primarily financial. When the desired benefit is co-commissioning or cross-agency working. | When an intervention to prevent a social problem from developing for an at-risk group is likely to be effective |

| Type of analysis to do |

Monetary value of economic, social, and political benefits using economic theory. Cost-benefit analysis. |

Root-cause analysis. Statistical analysis of how people ‘flow’ through the system, what are their needs on the journey and what is currently offered at what cost (to whom). Cost benefit analysis of successful prevention. |

| Strengths | Can help make the case for central government funding, co-commissioning or collaborative working. Cashable savings not a priority. Can provide a starting point if the service is completely new. | Develops understanding of root causes of problems. Can enable flexibility in delivery as different means of prevention are attempted. |

| Limitations | Can require considerable analytical resource. A budget line to pay an amount based on this method of calculation must exist or be created. |

Can create a large financing gap for providers (if the avoided negative outcomes would be a long time in the future). Risk of paying for the prevention of things that would never have happened anyway. |

| Resources | UK Treasury green book Unit cost database that has been developed by New Economy. |

What Works Centre evidence synthesis. Unit cost database. |

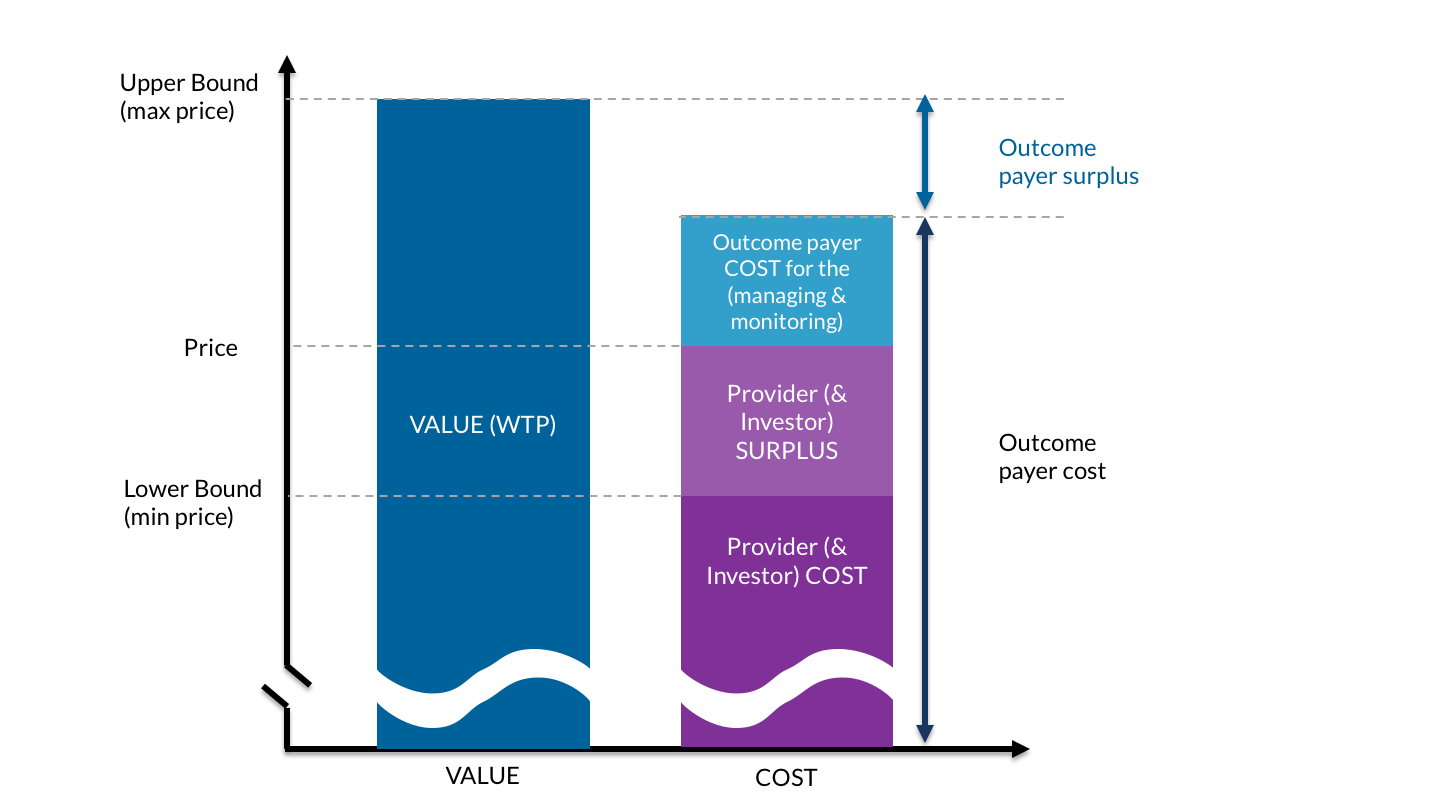

2.3 Estimating the costs

Estimating the cost allows the setting of a lower-bound to what the provider should expect to receive from the contract, if they achieve a satisfactory level of performance in achieving outcomes. The lower bound of the price paid for outcomes should cover the costs the provider (and/or investor) have to endure in order to achieve the outcomes at the level expected. As a result, it is useful for the outcome payer to derive an understanding of what these costs might be. Of course, if they do not achieve the expected level of outcomes, their costs will not be covered.

It is important to distinguish between the cost to the provider for delivering the outcomes (the lower bound), and the cost to the outcome payer, which includes any surplus (or "profit") the provider may seek (which the outcome payer will want to minimise) and management and monitoring costs to the outcome payer. This is illustrated in Figure 2.4.

While outcome payers may seek to minimise provider surplus / profit, underpaying for outcomes can be as dangerous to the success of an outcomes-based contract as overpaying, because it may mean that no bids are received, may discourage high quality providers, and may encourage cherry picking whom they work with i.e. focus their efforts primarily on people for whom the defined outcomes can be achieved most cheaply, whilst ignoring those who need the most help. This is discussed further in Chapter 3.

The importance of estimating provider costs may be reduced if you are operating in a competitive environment where real competition on price is likely to occur, and the market can be relied upon to deliver value for money. However, where there may be very few providers or investors in a position to deliver the contract, there may not be a competitive market, and a greater degree of transparency may therefore be needed around provider costs than would be necessary where a functioning provider market exists.

An example of how costs might be broken down into a number of components is shown in Table 2.2. This example assumes that the impact bond is being led by an investor who sets up a special purpose vehicle (see our guide for more on IB structures). In other impact bonds, these costs may be split between the investor and provider, and perhaps also an intermediary and evaluator as well.

It is important to note that whilst the operational costs of delivering the contract are likely to be easily the largest component, there are sometimes significant costs associated with development and design, contract set up and negotiation and evaluation.

| Cost Category | Cost Sub-category |

|---|---|

|

DEVELOPMENT & DESIGN Pre-contract signing search and information costs |

Due diligence of potential providers |

|

CONTRACT SETUP & NEGOTIATION Bargaining and Contracting Costs |

Legal advice on contract design (including tax advice & either external or internal) Financial advice on contract design (either external or internal) SPV Setup Costs Reworking of business and financial case |

|

OPERATIONS COSTS Governance, monitoring and evaluation costs |

SPV operational costs (including salaries) Performance management (Staff) Data management (Technical) Outcome reporting &/or compliance with validation method cost Service delivery costs (upfront payments) Service delivery costs (later payments) Governance costs (e.g. board meetings) Tax (total) Outflow to investors* |

| OTHER COSTS |

In outcomes contracts, the finance costs borne by the investor and/or the provider are passed on to the outcomes payer if the program is successful. These may vary significantly depending on the source of the finance, the amount of investment required, and the perceived level of risk of achieving enough outcomes to break even.

There are three ways that an outcome payer can try to gain an overall understanding of costs: market engagement, historical costs, or comparable services.

2.3.1 Market engagement

It may often be possible and desirable for outcomes payers to gain an understanding of the likely investor and provider costs of a proposed program through market engagement and/or asking for the information as part of a tender process.

2.3.2 Historical costs

This approach applies if the intended outcome requires a service that has been used previously on a similar target population. In this case, you should have an idea of the price of such services which enables you to get an estimate of the likely total cost of outcomes, provided that a similar service is proposed for the outcomes contract.

An estimation based on historical costs is often easier to pursue if an existing service is being re-let, as that gives a ready comparison. As there is already a service in existence to compare with, then a lot of the uncertainty about referral rates, level of need of the client group, and to some extent level of anticipated success, are also reduced. As we discuss later in "3.6. dealing with uncertainty”, in the case of IBs this may also imply that investor returns could be lower.

After finding an estimate of the intervention costs, it is worth considering the possible additional costs of an outcomes-based contract, as shown in Table 2.2. above. However, it is not necessarily the case that an outcomes-based contract is more expensive to deliver than a standard contract. The extra discipline of having to achieve outcomes in order to receive payment might drive increased efficiency, which is likely to bring down the costs of delivering a given number of outcomes.

2.3.3 Comparable service / reference costs

Where there is no historical service to compare, it may be possible to refer to comparable services which are likely to use similar resources/inputs. This should provide an approximate of expenses required to deliver the outcomes. Once again, additional costs specific to outcomes-based contracts should be taken into consideration.

2.4 Setting the price

Payment mechanisms should include generous enough payments to provide a quality service to the target population, which accepts that the risk taken by providers/investors of not succeeding needs to be balanced by the potential to make a surplus if they do well. Prices should be fair for all parties, high enough to be commercially viable and low enough to avoid windfall profits for investors and unnecessary expenditure by outcomes payers.

- Working downwards from the value. Where there are many potential providers, a “maximum price” can be set for each outcome based on the value calculation, or for the outcomes as a whole, and providers can be invited to bid at a discount against it. (There may be different discounts against different outcomes, in which case you can score on price based on the weighted average discount).

- Working upwards from the cost. Where the contract is designed in collaboration with a single provider, a “minimum price” can be set based on the cost of delivery estimate, and a price negotiated above that based on the distribution of risk between the parties.

Whichever of these is used, a number of assumptions will need be made, which will affect the price. These “parameters” are as follows, and are discussed in detail in Chapter 3.

- Cohort specification: how difficult it is to help the target cohort (harder cohorts demand a higher price)

- Level of improvement: how ambitious the target outcomes are (greater ambition demands a higher price)

- Likelihood of success: the level of uncertainty about whether the targets will be achieved (greater uncertainty demands a higher price)

- Timing of payment: when the payments are made (later payments demand a higher price)

- Additionality: how reliably the outcomes are measured to show they are additional to what might happen otherwise (greater reliability demands a higher price)

- Budgetary constraints: Whether there is a budgetary limitation on the total possible payment

The best way to analyse the effect of these parameters is to build a financial model, where different assumptions can be made, and the probable effect of these on the price explored.

An additional parameter might be currency risk, if costs are incurred in a different currency from that used to pay for outcomes (which can be the case in international development). This parameter is not discussed further.

Some of these parameters are illustrated in figure 2.4.

Often the analysis of these parameters is best done through active, structured engagement with market. We discuss different approaches to market engagement and procurement, and the pros and cons of these, in our guide to awarding outcomes-based contracts.

2.4.2 Assessing the value-for-money

Whichever pricing approach is used, a full and detailed assessment of value-for-money can be done. There is a full discussion of how this might be approached in the Appendix. There are three criteria that can be used for this (this is based on the UK’s National Audit Office and Department for International Development).

- Economy: minimising the cost of resources used or required (inputs) – spending less

- Efficiency: the relationship between the output from goods or services and the resources to produce them – spending well

- Effectiveness: the relationship between the intended and actual results of public spending (outcomes) – spending wisely

Factors which affect the price

17 minute read

As outlined at the beginning of this guidance, the price you set will interact with the cohort definition and outcomes you expect to achieve, which is why the approaches described in Chapter 2 only give you a sense of the upper and lower bound, rather than a final answer. You need to strike a balance between multiple considerations in order to create useful incentives to achieve outcomes. There are two risks if these considerations are not taken into account. The first is the risk of underpaying for outcomes – in which case you will end up with a contract that is impossibly expensive or risky for a provider to deliver (and most likely none will offer to). The second is the risk of overpaying for outcomes – in which case providers make unreasonable profits / surplus and you do not get value for money.

3.1 Cohort specification

As a basic rule-of-thumb, cohorts that are harder to help or have further to ‘travel’ in order to achieve the desired outcomes will be more costly to work with, as they will need more intensive support. As we describe in the likelihood of success section below, harder-to-help cohorts will also tend to be less likely to achieve the outcomes than easier-to-help ones. This increases costs. These increased costs need to be compensated through the payment mechanism.

Cohort specification will enable you to (i) define a specific cohort of people with key characteristics and (ii) estimate variation in difficulty-to-help amongst beneficiaries. How easily can you describe the characteristics of those for whom you are commissioning the service? The more targeted and similar the cohort, the most straightforward the approach to price setting can be. On the other hand, the more diverse the needs are of a cohort of people who exhibit the specific problem which is being targeted, e.g. being homeless, or being unemployed, or having a drug problem, the more an outcomes-based contract may be beneficial, because of the difficulty in specifying a single service intervention applicable to the whole cohort.

The more comparable the levels of need in a cohort, the less the risk of ‘perverse incentives’ (for example, there is less risk that a provider may ‘cherry-pick’ and only work with ‘easier cases’). This makes knowing how much to pay easier: it can be discovered through market engagement or by examining the cost of in-house provision.

In many cases, however, it will be difficult, or incompatible with the purposes of the program, to identify a cohort of sufficiently similar people, especially for services aimed at supporting people with complex needs. Often a cohort will be large and diverse with broad a range of needs and potential intervention / support packages. In these cases, it is still possible to reduce the risk of ‘cherry-picking’, in three ways:

- ensuring a referral process that is independent of the service provider. For example, using professionals not attached to the service provider to decide who is eligible for the service. This prevents the provider being able to pick easier cases for themselves, as someone else is deciding for them.

- preventing over-recruitment by setting payment triggers linked to the proportion of referred beneficiaries who achieve the outcome, or capping the number of referrals. Over-recruitment may occur when you pay for each individual who achieves the agreed outcomes. Without safeguards, paying for individual outcomes may create a perverse incentive by which providers may accept (or recruit) very high number of referrals and work only on ‘easier cases’ to trigger payments, ‘parking’ a high proportion of difficult cases. If a certain proportion of the cohort needs to achieve an outcome to trigger payment, or if the number of referrals is capped, they cannot do this.

- setting different prices for different sub-groups within the cohort. This means the providers can be paid more for resolving more difficult cases. It should be noted that this adds complexity and can create other unintended effects, as the criteria for selection of the sub-groups may not align well with the real costs of achieving outcomes for them.

3.2. Level of improvement

A key part of defining payable outcomes is setting a point of improvement from a baseline at which payment is made. This can be referred to as the ‘threshold’, ‘target’, ‘metric’, ‘milestone’, or ‘trigger’ at which the payment outcome is deemed to have been achieved. We will use the word ‘target’ here. Essentially, it means defining ‘what does good look like’ or ‘what is a meaningful improvement’? The basic rule of thumb here is that the greater the level of improvement desired within the cohort identified, the greater the value of the improvement and the more costly it is likely to be for providers to achieve the targets, as they will need to offer more intensive support, leading to a higher price paid for the outcomes. In the last section we discuss ways to tackle uncertainties around a provider’s likelihood of achieving the level of improvement set out.

The longstanding discussion in education about how to measure learners’ performance is perhaps a helpful analogy to think about the forms these targets can take. The question is whether student performance is best measured by attainment / proficiency (meaning a student’s performance against a universal benchmark at a given time), or progress / growth (meaning a student’s performance improvement or decline over time, relative to the average or their own starting point). Proponents of progress or growth scores say that using attainment or proficiency scores encourage teachers to focus less on those students who fall far below the attainment threshold, and unfairly stigmatises schools whose intake has more of these students. They argue that we should be using progress or growth measures if the goal is to assess schools on how well they serve students, not on which students they serve. To take an example from the UK, the long-standing but now abandoned ‘A*-C’ measure of GCSE grades is an example of how an attainment-based cut off can have these effects, as it encouraged schools to disproportionately focus resources on students on the C/D borderline, at the expense of those expected to get lower and higher grades.

In the world of defining outcomes, the same logic holds true. You can think about fixed, binary targets – like an ex-offender not re-offending during a set period, or someone who is homeless living continuously in accommodation over a long period – as though they are attainment scores. Indeed, evidence suggests that they risk focussing providers’ attention on beneficiaries who are around the cut-off point, often at the expense of individuals who have further to travel. For instance, a binary payment for ‘not re-offending’ would incentivise providers to work with offenders who only offend few times to bring this down to zero, rather than working to reduce reoffending rates for people who have a history of many offences (without being able to eliminate them entirely).

Targets that reflect the ‘distance travelled’ may be more accurately estimated and reduce these risks, but it can be more challenging to measure them – typically requiring more granular and ‘sensitive’ measures or measurement approaches. In taking this approach, you will need to either (a) measure, and take into account, an individual or cohort’s starting point, and determine an acceptable amount of progress to have made by the end; and/or (b) show degrees or ‘steps’ of improvement, and add extra payment targets to reward these. Either of these approaches adds complexity, but it is key to think about them and to create a solution that addresses these points.

On the other hand there are areas where distance travelled towards a goal may have little value unless the goal is achieved. For example, supporting a person who is a long way from being “work ready” to being closer to work ready may not be worth much if that person still doesn’t get a job, unless the work done has other benefits such as improved mental health.

You can read more about tackling these issues in our guide to setting and measuring outcomes.

3.3 Likelihood of success

All stakeholders in an outcomes-based contract need to understand how likely it is that the project will achieve the proposed outcomes. If outcomes seem harder to achieve, either because the cohort is difficult to help or because the desired level of improvement is high, then the probability of achieving outcomes will be lower, and the contract will be deemed riskier – and risk demands compensation. In the case of impact bonds, social investors backing bids to provide working capital to finance the contract will take this into account in the level of financial return they expect – higher risk calls for higher potential returns.

There are a number of ways to make future performance projections and you will want to use a combination of all of these. To have a goal in mind, it is helpful to identify a range of values. For instance, you can estimate a ‘minimum expected scenario’ (sometimes termed ‘base case’), a ‘best case scenario’ and a ‘worst case scenario’.

Using historical data – If you have well documented data and a good historical data record, these would be a good starting point for a first estimate of the likely success of the project and how many outcomes are likely to be achieved.

Using existing evidence / academic research – in some cases, there will be existing evidence or academic research indicating how successful a particular programme or approach will typically be. For example, the Ways to Wellness social prescribing programme used the results of a pilot programme carried out by Nesta to predict how successful the project would be.

Running a procurement process with dialogue – by running a procurement process that allows for dialogue with multiple providers, you can compare competing claims on likelihood of success, and whether the estimates you are being given are based on robust assumptions. While providers will naturally want to show they have the greatest chance of success, it is important to assess how realistic the prediction is – or whether it seems overly optimistic. Please refer to the guide on awarding outcomes-based contracts for more about the different procurement approaches that allow for this sort of dialogue to take place.

Using the expert judgment and data of a provider – in some cases, you may be procuring a completely innovative service, or working with a new cohort who have not been previously identified or worked with. In these cases, you may be using an outcome based contract because you are not able to determine the likelihood of success and need to rely almost entirely on the projections of a provider, which you will want to test the rationale for. The risk is higher in these experimental scenarios, though the contract enables some (or all) of the financial risk to be transferred.

Use a learning contract or pilot period – You could procure services anticipating an initial period where you closely monitor the implementation of the intervention and improve your understanding of what level of outcomes it is feasible to expect. This would also allow you to identify the key barriers and strengthen your performance management system and payment metrics. At the end of this initial phase you can firm up your payment mechanism in collaboration with other stakeholders. There are examples in the UK of approaches like this being used. You still need to have a well reasoned baseline scenario before starting the contract, and should use this flexibility as a genuine opportunity for learning in partnership with other stakeholders. Good stakeholder relationships and a level of trust, as well as a clearly defined process for future price adjustments, are required to avoid the danger of the provider exploiting the flexibility to ‘move the goalposts’ in, say, year 3 of a 7 years contract. Our guide to awarding outcomes-based contract has more detail on how contractual terms can be used to safeguard this approach.

3.4. Timing of payment

The timing of payments is important. Generally, the later the payments can be, the more likely it is that they will align with the achievement of your long-term policy goals, as you are more likely to know if the ultimate outcome is both achieved and sustained. There is also a benefit to the outcome payer of later payments, because money can be used for other things in the interim. Furthermore, in economies where inflation is high, there may be an additional benefit to later payment (unless you choose to include inflation in the pricing). These timings benefits can be quantified by using discounting (as shown, for example, in Chapter A6 of the UK treasury’s Green Book).

Often, though, there are practical implications for providers (and investors) to such long-term payments, meaning you should consider adding payments for ‘proxy’ or ‘lead’ outcomes (or even outputs as long as the final target in an outcome) in addition or as alternatives. You can read more about identifying these sort of outcomes in our guide on setting and measuring outcomes.

The cost implications of the timing of payments is all to do with the fact that an outcome based contract creates a financing need for a provider organisation. A provider provides a service upfront but is not paid until later, when outcomes are achieved – so they have to use their own money, or borrow it from someone else (like a social investor). The effect of different timings on this is best illustrated with a simple example:

- Your goal is to get 100 people who regularly sleep rough into stable accommodation.

- It takes your provider on average 6 months to get people into accommodation.

- They will then provide up to 12 months of ongoing support to people once they are in accommodation, to ensure they are stable.

- They are paid once people have spent at least 12 continuous months in stable accommodation.

- This all means your provider has 18 months of outgoings for 100 people, with income coming at the end.

- They will go heavily into the red for the delivery of this contract – likely to mean they will need to borrow more money or secure investment to keep delivering the service.

- This borrowing (or investment) will come with an interest payment (or return expectation) which will have to be built into the contract cost.

The same basic principle applies whether providers self-finance, take out a loan, or receive backing from a social investor who pays them a traditional service fee and takes the financial risk on themselves. The longer the provider or investor has to wait to receive payment for the delivering of outcomes, the higher the strain on their finances, and the greater the cost. On the other hand, later payments help with the outcome payer cashflow and enables them to use their money on other projects, as well as reducing the risk that they are wasting their money on outcomes of limited value e.g. a homeless person who sustains accommodation for a short time but then becomes homeless again. The outcome payer might therefore attempt to ensure the sustainability of results by setting both early and late payments in a way to keep the providers (and/or investors) incentivised.

| Pros | Cons | |

|---|---|---|

| Earlier payments |

Lower risk for provider (& investor) Guarantees some early indications of progress |

Greater risk to outcome payer Weaker incentives for provider (& investor) to achieve long-term outcome |

| Later payments |

Lower risk for outcome payer Defers outgoings for outcome payer, so cash can be used elsewhere |

Greater risk for provider (& investor) Can be complicated to budget for uncertain future payments |

You could add an additional earlier payment, for example at the end of 6 months, for any participant who has enteredaccommodation. This is not really the goal you are looking for – as they may soon return to sleeping rough – but, it means your provider would expect to get some income sooner, so will go less into the red, need to borrow less money to run the contract, pay less interest, and require a lower amount to be built into the contract cost.

In addition you may consider payments for activities and outputs as well as for outcomes. This will have much the same effect in enabling the provider to get some payment sooner, but at the possible expense of reducing the focus on desired outcomes, or alignment to the policy objectives.

In short: outcomes which are paid early on in the delivery phase can lower the cost of financing for the providers (and/or investors), but may lessen the focus on longer term outcomes that are usually more aligned with the overarching policy aims of the project.

Note that a greater focus on longer term outcomes, as well as increasing the financing amount, can also increase the provider’s (and/or investor’s) perception of risk. This can result in an increase in interest payments or financial return expectations. This is discussed further in the next section, ‘likelihood of success’.

In projects which feature both early and later-term outcome payments, you need to be aware that your payment structure may create incentives for providers to treat these outcomes ‘interchangeably’ and focus solely on delivering short-term outcomes for a higher number of beneficiaries. There are ways to mitigate this: having a limit on the total number of participants whom the provider is allowed to work with within an overall payment envelope (or “contract cap” – see section 3.6 below), and/or higher payments for longer term outcomes.

Although later payments help with the cashflow and cost of capital for outcome payers, it is important to plan their payment in the budget in advance. Public sector commissioners can often only pay money in the year they have the money budgeted for. So it is important to profile the expected level of outcomes payments in each financial year, and if possible build in some flexibility to move money between financial years in case outcomes are achieved later than initially expected.

3.5. Additionality

“Additionality” is one of several related concepts – the others are attribution, counterfactual, and deadweight. While these terms can seem daunting if you are not familiar with them, we use them because they describe useful concepts and some are increasingly widely used.

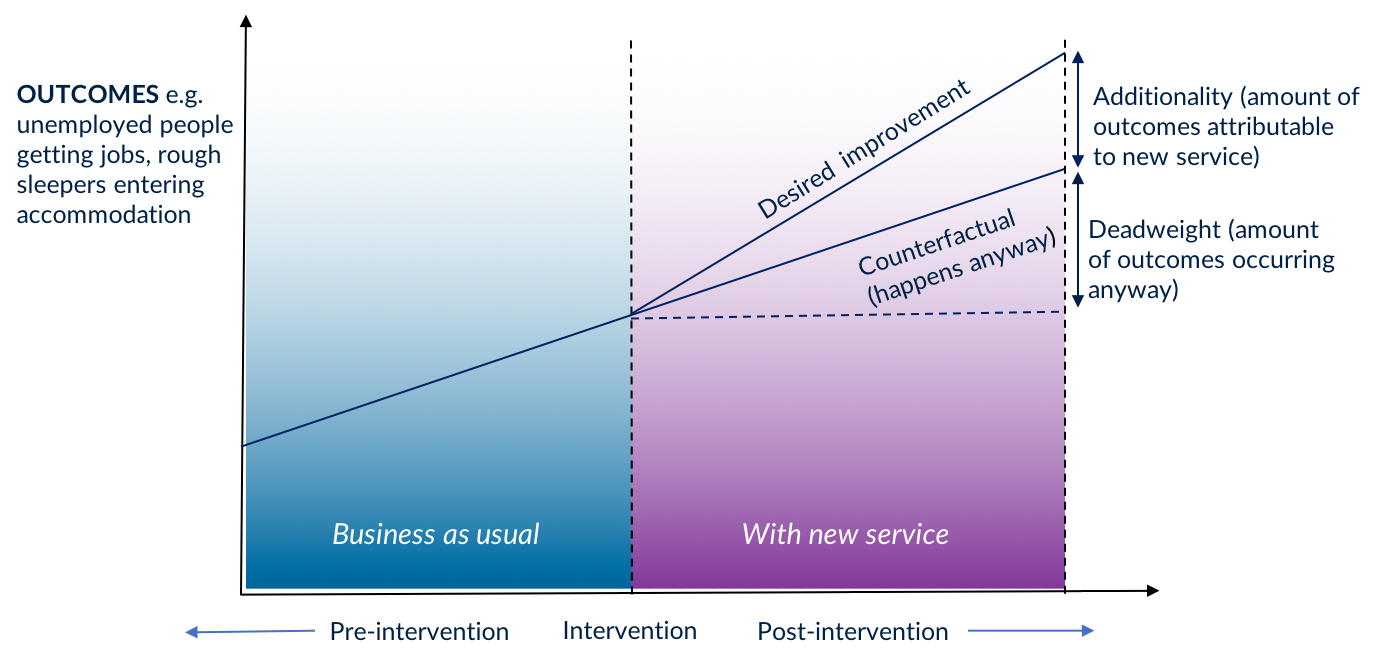

“Additionality” refers to an impact that is “over and above what would have happened anyway”. You could describe it as “over and above business as usual” or “what we currently expect to happen”. A description of what would have happened anyway is known as the “counterfactual”. Determining the level of “additionality” in a robust way helps to show that any positive effect was indeed caused by the work that was done – this is the concept of “attribution” (i.e. it shows that the outcome is “attributable” to the intervention).

The answer to “what would have happened anyway” is very rarely “nothing”. For instance, in projects aiming to support people back into work, an obvious outcome payment is sustained employment. However, some of the participants might have found an employment over time even without the intervention. The amount of this natural improvement that takes place is called the “deadweight”.It is worth pointing out that deadweight can also work in the other direction e.g. if something happens to other participants to make them less likely to get work than they were at the start of the project.

Unfortunately, it is never possible to observe “would have happened anyway” unless you know how to create a parallel universe, and so the best you can do is to estimate it.

If you are running a quantitative evaluation alongside (or as part of) the contract, then it is feasible to think about using statistical methods to estimate “additionality”, such as experimental (e.g. randomised-controlled-trials) or similar quasi-experimental techniques (e.g. pre test-post test). These tend to use some sort of comparison group who share similar features to the cohort being worked with, but who do not receive the same service. We explain these techniques in our introduction to evaluation. For instance, the Peterborough SIB and the Ways to Wellness SIB each estimate additionality by using a comparison group technique.

If you are using one of these techniques as the basis for measuring the outcomes you are paying for, you will have a good degree of confidence that those outcomes are attributable to the intervention. The risk of paying for things that would have happened anyway will be reduced, and there is no need to adjust the price set at the start to account for these considerations.

Often, it is not practical or affordable to use a comparison group to estimate additionality as part of the outcome measurement approach. When this is the case, you should think about factoring a prediction of what the deadweight might be into the price you offer. If the contract is using a “proven” intervention, there may be previous research and/or evaluations that will give you a reasonable indication of the likely level of additionality for that intervention. Alternatively, you can estimate additionality by articulating a “business as usual” scenario, and comparing it to various success scenarios for the new service. If you can access the right data, you might do this through an analysis of historical trends for the particular cohort that is eligible for the intervention, and project those trends in the future. There will be a degree of uncertainty and you might include a range of scenarios which account for high- and low-estimates.

Be aware that this extrapolation into the future may be inaccurate, especially for longer-term outcomes, as other external factors could influence the trends positively or negatively – such as a change in the economic outlook or in other areas of policy. In defining additionality using past trends, you could end up paying for outcomes that would have occurred anyway, because changes outside the control of the provider are making the outcomes easier to achieve. The reverse is also true: you may end up not paying for outcomes that the provider has legitimately achieved, because changes outside the control of the provider are making the outcomes more difficult to achieve than they would have been in the past. As we explain in our guide to Setting and Measuring Outcomes, you can mitigate this by aiming to set outcome measures and targets that are less susceptible to such external factors, but it is difficult to eliminate this risk entirely.

Although such projections carry a level of uncertainty depending on the quality of analysis and the eco-political stability of the study group, they provide us with useful information of the expected outcomes to help communicating better with other stakeholders (see more on uncertainty, optimism bias, and risk in Annex A5 of the Green Book and international equivalents.)

As a general rule, you should adjust either the price or total payment for outcomes downwards if you believe some outcomes would happen anyway (i.e. there is “deadweight”) but you don’t have confidence that you will be able to accurately determine how many (which you might do by measuring a comparison group). This is a legitimate measure to avoid paying for things that would have happened anyway, and to ensure good value-for-money to taxpayers. The possibility of price adjustment should be covered in the contract documentation. See more on this in our guide on awarding outcomes-based contracts.3.6 Risk of overpayment and setting a payment cap

1. Setting a cap on the total payment to providers or on the number of beneficiaries

You can consider setting a cap linked to the available budget for outcome payment. Consider the following relationship:

Total Payment = Payment per outcome x Number of people receiving the service) x Likelihood of success in achieving each outcome

In this approach, you will already have established a price per outcome, so you are setting a payment cap based on a maximum number of beneficiaries for which you will make payments under the ‘best case’ likelihood of success; i.e. Maximum pay is expected when ‘Successful Outcomes’ is equal to ‘Best Case Scenario’. You need to consider that this makes it unlikely the provider would continue investing effort and resources in providing the interventions to more people, as this would be at their own cost. Some providers (or the investors providing the finance) might continue to deliver the service anyway as they value the achievement of outcomes for their own sake and can access the required extra funding. You could discuss in advance with the provider what they expect to do if the cap is reached.

In some cases the cap follows from identifying a specific cohort. For instance, the “Street Impact” London Rough Sleepers SIBs identified the target cohort as consisting of 415 named individuals identified as sleeping rough in a particular dataset.

2. Setting a cap on the total payable outcome per individual

You may have defined a number of different outcomes that you will pay for as and when an individual in a cohort achieves them. As described earlier, this could be because your cohort is diverse, or because you want to include an earlier payment and/or reward progression towards an end outcome. If every individual in the cohort achieves every one of the available outcomes, you will overshoot your budget. However, rather than limiting the overall payment across a cohort, you may want to consider a cap to limit the total payment on each individual. This type of cap signals to providers the need to balance doing intensive work with a single individual with their ability to engage with a higher number of individuals overall (an ‘equity’ consideration). It also helps to protect from the possibility that providers focus on individuals who are ‘easier’ to work with, and who can progress through multiple outcomes more quickly. This is especially helpful when considering that these individuals were more likely to achieve some of the outcomes even without the intervention.

Can a separate cap be set on the provider’s surplus / investor returns?

Setting a payment cap as described above allows you to limit the return that investors can expect to earn from the project. If there are no investors, the same principle applies, but the ‘return’ would be reflected as provider profit or surplus. Providers and investors can use a number of methods to determine the level of surplus or return they anticipate, such as carrying out a financial sensitivity analysis. This analysis plays out a number of scenarios based on the expected outcome success levels.

Investors may be able to take risks on a particular project where they can take a portfolio approach. Across a portfolio of projects that they support, they expect that some projects will be more successful and lead to a higher return, whilst others may be less successful and lead to a loss. If you set a payment cap that limits investor returns, the investor may also wish to discuss a ‘floor’, i.e. a minimum payment that limits the total loss they could incur.

It is worth mentioning that there is not necessarily an inherent need to cap surplus or returns, as in a well-designed payment mechanism, these will be higher when you are getting more outcomes, which is the aim.Case study 1 - West London Zone social impact bond

8 minute read

1. Introduction

Project background

The West London Zone (WLZ) social impact bond (SIB) launched in 2016 and is ongoing. It is the first SIB to launch using the “collective impact bond” model.

Core project stakeholders (and their project roles) include: WLZ (service provider), the London Borough of Hammersmith and Fulham (LBHF) (co-commissioner), the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea (RBKC) (co-commissioner), The National Lottery Community Fund (co-commissioner), local schools (co-commissioner), private philanthropy (co-commissioner), and Bridges Fund Management (BFM) (investor).

WLZ is an organisation that partners link workers, charities, schools and other local organisations to support children and families.

Aim of payment mechanism

- If a child from a disadvantaged community in West London, United Kingdom, who is at risk of negative outcomes in life (based on a combination of risk factors)…

- … has an measurable improvement in …

- … social and educational outcomes …

- … as measured by activity participation, service interactions, and a defined set of outcome measurement tools…

- … over two years…

- … based on engagement milestones and compared to their baseline at the start…

- … then we will pay an agreed amount based on average project delivery costs per participating child.

2. Project scope

Target Population

The project targets children aged 5-16 in disadvantaged communities in West London who are at risk of negative outcomes in life due to being ‘off-track’ in school and in their wellbeing. The project covers the northern parts of two Local Authorities in West London: the London Borough of Hammersmith and Fulham (LBHF) and the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea (RBKC).

Each authority has a separate SIB contract, though the contracts share the same features.

Aim

The project targets improvements in social and educational outcomes across several areas, and the contracting authority pays out based on children showing a measurable improvement. These milestone payments were negotiated among stakeholders.

Intervention/Theory

The project funds WLZ to offer a 2-year tailored programme for each child that addresses a range of needs and builds a variety of strengths and skills empowered by their link workers, who are based in their schools and work with children and families alongside multiple local partner charities for specialist support. WLZ contracts its charity partners and operates a practical shared delivery relationship between the WLZ link workers and the delivery partner session leaders on the ground. Most, but not all, of West London Zone’s work is funded through a social impact bond (often referred to as a ‘collective impact bond’).

Once the cohort is identified, WLZ link workers approach at-risk children and their parents/carers in partnership with the child’s school. The link worker builds a trusted adult relationship with these parties while co-designing the child’s individual support plan. The child’s individual support plan is developed in a co-design phase which uncovers information about the child’s strengths, interests and skills – which informs design of a phased support plan. Developmental support is conducted by WLZ link workers and WLZ delivery partners (32 as of Autumn 2018) provide specialist support to participating children.

The project was inspired by the Harlem Children’s Zone, a charitable enterprise in New York initiated to support children from ‘cradle to college’. The premise of the West London Zone intervention lies in the idea that issues relating to children living in deprived neighbourhoods are complex and cannot be solved using a single agency or intervention.

3. Payment foundations

Approach

WLZ values outcomes based on expected costs and success rates for the 2-year programme. In 2015-2016, a pilot implementation study was undertaken to inform these estimates. WLZ was the first time this set of stakeholders had worked together in this way.

The pilot was philanthropically funded and run in parallel with the development of the social impact bond financing model. The set up, delivery, and evaluation of the pilot together with the SIB development cost £580,000.

Impact estimation

The WLZ pilot implementation study offered insights into what performance could be expected when otherwise individual services were combined in a new delivery model.

Value estimation

Project milestone payments in the WLZ SIB are based on:

- Average delivery costs per participating child (from pilot study);

- Iterative discussions among WLZ and BFM.

Delivery costs per participating child incorporated the assumption that different children would require different support. This was converted into an average figure for payment value estimation.

Iterative discussions among WLZ and BFM took into account: average delivery costs per participating child, payment proportion assigned to different milestones, the likelihood of success among the cohort of achieving milestones.

4. Payment specification

Cohort

The project identified eligible children in disadvantaged communities in LBHF and RBKC using risk factor analysis. Analysis steps are outlined in Table 2. WLZ expects to work with at least 700 children over the course of the SIB-funded project. Cohort identification data provides the baseline for measuring progress of children participating in WLZ services. Step 5 in the risk factor analysis (target cohort agreement) ensures that both schools and councils verify children for inclusion, which reduces the risk of perverse incentives leading to WLZ “cherry picking” children with a higher likelihood of reaching improvement milestones (and associated payments).

The risk factor analysis combines school level administrative and demographic data with interviews with school staff, and is verified using the WLZ My Voice survey. This collects data via multiple self-reported measures. This helps determine children’s emotional wellbeing, trusted adult networks, engagement with school, peer relationships, and parental relationships.

| Step | Explanation |

|---|---|

| 1) Prioritisation and participation |

WLZ service is school-based and only includes children at participating schools WLZ prioritises schools for participation based on combining publicly available data on demographics, progress, attainment gaps and absence rates. Prioritised schools then have a choice on whether to participate in WLZ SIB |

| 2) Data generation (school) |

Following school participation, WLZ compiles school-level data to assess individual children's economic disadvantage (using the proxies of receipt of free school meals or 'pupil premium' payments), school attendance, and attainment levels of English and Maths. Additional qualitative input is collected through discussion with staff to gather their insights into individual children's school engagement, wellbeing, and family context (incl. parental engagement with the school and presence of trusted adult network). School staff also highlight if an individual child has: an Education, Health and Care Plan, a Child Protection Plan, involvement with Children and Adult Mental Health Services (CAMHS) or any other social services. |

| 3) Data generation (survey) |

WLZ collect additional data Children 9-16 years old are eligible to complete the ‘My Voice’ survey, which is a composite of multiple self-reported measures. Children 5-8 years old are eligible to compete the Strengths and Difficulties questionnaire, either themselves or via a parent or teacher on their behalf |

| 4) ‘At-risk’ identification |

Each piece of collected data has a ‘risk threshold’. Thresholds are determined via national datasets, academic paper, or government policy. Individuals marker as above a risk threshold is deemed ‘at risk’ on given characteristics and assigned ‘1’. Anyone below the risk threshold is deemed ‘not at risk’ and assigned ‘0’ for that characteristic. Children with the largest ‘at risk’ levels, summed across all characteristics are shortlisted for inclusion in the target cohort. |

| 5) Target cohort agreement | WLZ and school staff confirm those to target from the list |

Improvement

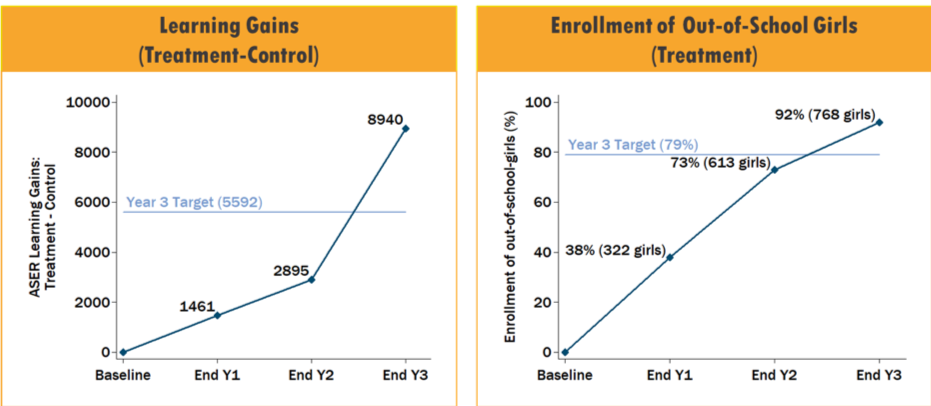

The impact of services provided – improvement in social and education outcomes – is measured via a “rate card” of progress outcomes. This approach does not involve a control group, but rather achievement of defined milestones. Payments are allocated across six “milestones”, which are listed in Table 1.

Timing and structure of payment

Outcome funding is divided equally across the six possible outcomes payments (Table 1). Half is allocated towards service engagement (#1, #2, #3) and half for outcome payments (#4, #5, #6).

There was a different payment milestone framework at project launch, but this was revised after a year as WLZ and commissioners determined that the original mechanism was too complex, and not all of the data could be collected in the way required to conduct the measurement.

Additionality

The WLZ SIB uses historical baselines for the outcome payments #4, #5, and #6. Historical baselines use the data collected during the risk analysis / identification process described above.

| Payment # | Milestone(s) | Timing | Payment % |

|---|---|---|---|

| No payment | Identification - Child is identified as eligible for early intervention support. | - | - |

| 1 | Sign up - Child/family gives consent to participate. | FY 1 - Q4 | 17% |

| 2 | Engagement - Sufficient interactions with link worker and attendance at partner support payable at the end of year. Applicable if child attends at least six formal engagement meetings with their link worker and attends at least 75% of the support sessions scheduled with partner charities and link workers. | FY 2 - Q1 | 17% |

| 3 | Engagement - Same interactions and attendance as required in Payment #2, but for following year. | FY 3 - Q1 | 17% |

| 4, 5 & 6 |

Achievement - Applicable at the end of 2 years of engagement, if one engagement payment (2 or 3) has been met. 3 final payments in a possible "rate card" of 7 at end of 2-year programme. Payments must include at least one outcome from "academic"/"attendance" outcomes. Rate cards payments include:

|

FY 3 - Q2 | 49% |

5. Payment certainty

Likelihood of success

Likelihood of success is based on estimates of how many children might be expected to improve by participating in WLZ’s service, based on the pilot implementation study. WLZ and BFM agreed a ‘likelihood of success’ for each outcome, which incorporated expectations that most service recipients would engage with services (milestones #1, #2, #3), but fewer would achieve end outcomes (milestones #4. #5, #6).

Accounting for different scenarios

WLZ SIB stakeholders used a sensitivity analysis to account for different project scenarios. Table 3 outlines the results of this analysis for base, high, and low likelihoods of success rates of children participating in the WLZ SIB. Figures used are examples, rather than than the actual ones used.

| Payment # | Milestone | High | Base case | Low |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Sign-up | 100% | 100% | 100% |

| 2 | 1st annual engagement payment | 90% | 80% | 70% |